When the RMS Titanic sank in 1912, the outraged public demanded tectonic shifts in the shipping industry. One such development was the 1915 Seamen’s Act in the United States, requiring vessels to carry enough lifeboats or rafts for everyone on board. And while these measures must have saved countless lives in the 110 years since then, there is one occasion when they sometimes get the blame for killing more passengers than the Titanic.

On 24 July 1915, the steamer SS Eastland capsized while docked in Chicago, taking 844 lives in a harrowing scene that haunted the city for generations. Hosting a lively crowd of 2,500 workers of the Western Electric Company on their annual picnic, the unassuming laker developed a list, and while the crew made attempts to right her with ballast, she rolled to her side, crushing or drowning a third of the passengers. Although the Eastland had been notoriously unstable since her launching in 1903, some experts now believe the critical factor in the sinking to be the extra weight from the lifeboats and rafts, added in compliance with the Seamen’s Act. But is this a fair judgment, or just a volley of sensationalism?

Good Design Gone Bad

The Michigan Transportation Company was a newly founded enterprise, anxious to enter the lucrative market of the Great Lakes. Freighters of the time carried passengers and fresh produce between Chicago and the vast countryside around the lakes, serving as a pillar of the local economy and securing a steady income to operators. The Eastland was the first and last passenger vessel designed by the Jenks Shipbuilding Company of Port Huron. For this reason, the shipyard often gets the blame for an inherently unstable design, but the real story was more complicated.

In defense of Mr. Sidney Jenks, he did a decent job at first – the initial blueprint promised a solid workhorse, not much different from the other steamers plying the vicinity. But, as always, economic considerations weighed in, and the Eastland ended up shorter, taller, and somewhat top-heavy. To counter the reduced metacentric height, Jenks installed ballast tanks, but they turned out too wide, allowing the water to slosh to the sides when partially filled. The worst part, however, was when she failed to meet the speed threshold of 20 miles per hour, guaranteed in the agreement with the Michigan Transportation Company. Even though the Eastland reached 19 mph in the trials, the shipyard still owned $2,500 to the owner for every quarter of a mile below the target. Under such financial pressure, sober engineering quickly gave way to rash decisions.

The Eastland returned to the yards that same year, leaving with reduced draft and a heavy air-conditioning system, both of which only exacerbated the stability issue. To the owner’s delight, however, she was fast, winning a race against her fiercest competitor the City of South Haven in 1904. But the applause was short-lived, as she almost tipped over that same year with 3,000 passengers on board. Another near miss occurred two years later, arousing public indignation and affirming the Eastland’s reputation of a “cranky” vessel. In 1909, she returned to the yards to have all passenger cabins removed and her smokestacks shortened, but these modifications did not prevent yet another hair-raising episode, when she listed 25⁰ while loading in Cleveland. She was flat-bottomed and top-heavy, and nothing seemed to fix that. Tragedy was a matter of time.

The Picnic

The time came in the summer of 1915, when the Western Electric Company chartered several vessels for their annual picnic – a day trip to Michigan City, eagerly anticipated by the company’s employees and their families. In the lively bustle of the morning, no one at the wharf seemed to care about the Eastland’s alarming history, as they rushed along the gangplanks with their families to find a place on the top deck. After all, the Federal Government had enforced strict safety regulations to prevent another Titanic, and the Eastland was now creaking under the weight of numerous lifeboats and rafts.

As she filled with passengers near capacity, the ship leaned to starboard. Captain Peterson, eager to vacate the wharf for the next boat, remained calm and continued the hasty boarding at a rate of one passenger per second. After all, she was just being her usual “cranky” self, and the Captain was not letting her temper interfere with his tight schedule.

Don’t forget to visit The Shipyard Shop!

Two decks below, however, Chief Engineer Erickson was losing composure. Hasting to right the ship, he ordered the intake of ballast water. The result was minimal, since the Eastland had been poorly loaded, with most of the coal on the portside. She straightened up and then leaned to port. Erickson’s anxiety grew as the list increased, and he ordered filling the starboard tanks, but the ballast water was already sloshing, and the lifeboats above weighed down too heavy to counter. The Eastland was at a tipping point.

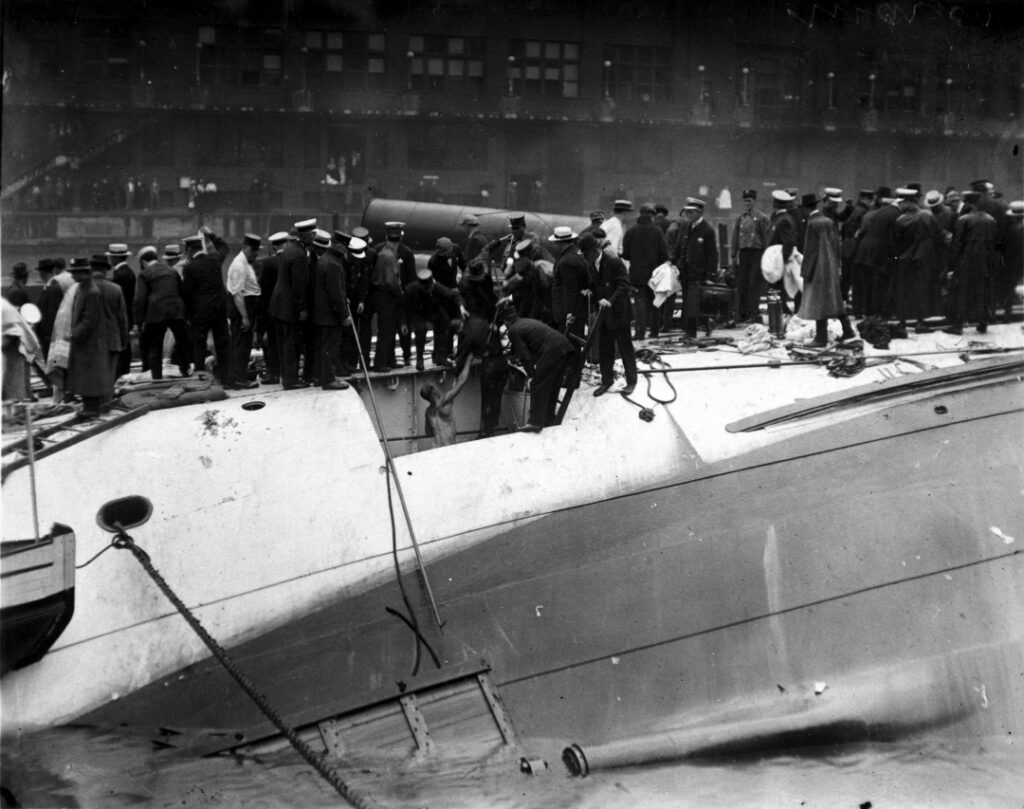

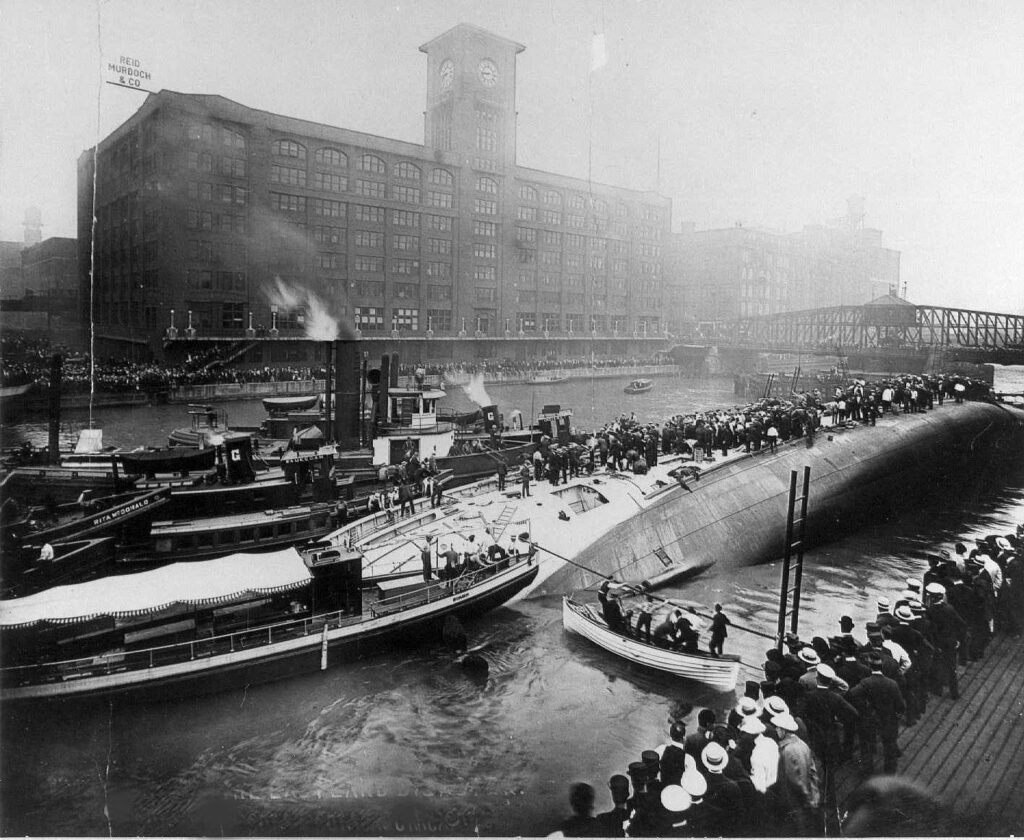

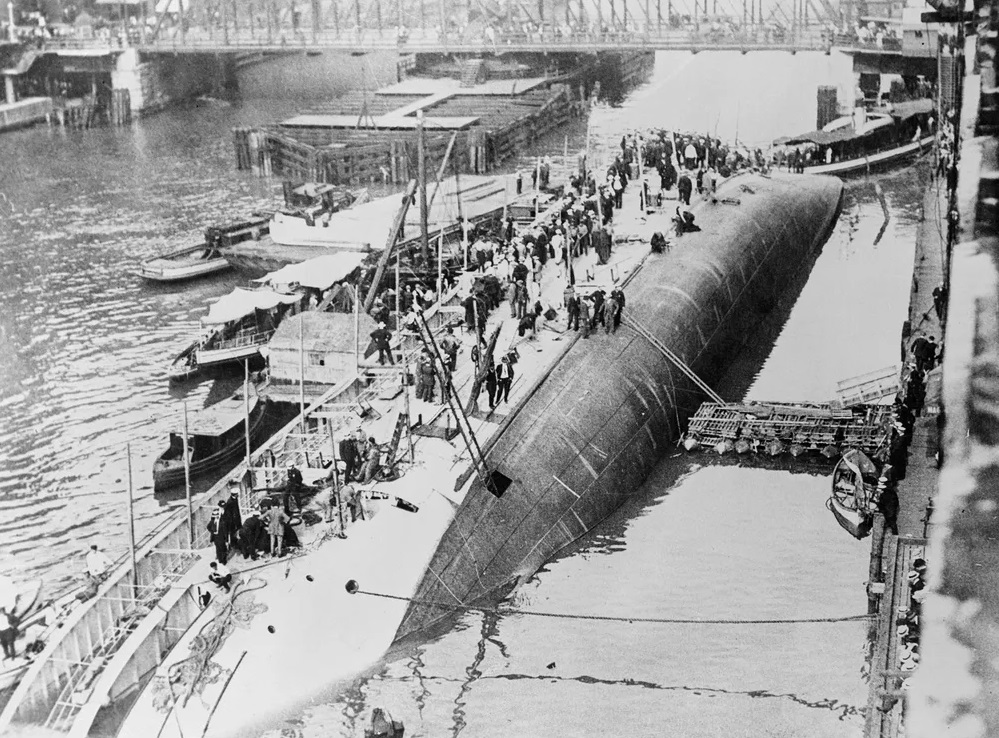

Disaster struck swiftly, as the overloaded vessel rolled to her side, resting half-submerged in the river. The scene that unfolded traumatized an entire generation of Chicagoans – dozens crushed by the impact, hundreds in the water fighting for their lives, those beneath them drowning, unable to rise to the surface. And as the terrible screams began to subside, a dense carpet of bodies covered the river. Entire families perished in the frenzy, some with no kin left to claim their remains.

So, Was It the Titanic’s Fault?

Blaming the Seamen’s Act for the SS Eastland horror may be a catchy line, but it severely oversimplifies the situation. To use a cliché, the harrowing incident was a perfect storm – everything that could go wrong, did. The need for aggressive publicity forced her designers to make her faster at the expense of stability. The owners tried a series of cosmetic remedies to the instability problem but failed every time with yet another incident. On the tragic day, the crew made a hasty effort to prevent the capsizing, but their actions were not coordinated by the captain and failed to even delay the inevitable.

Finally, there was the 265-footer’s capacity for 2,500 passengers – in comparison, many modern ferries of that size carry less than half of that. Yes, the extra lifeboats were indeed the proverbial straw on the camel’s back, but the camel was doomed long before that. Tragedy was a matter of time, and it is just as inconceivable now, as it was then, how long the people involved just watched and waited for it to happen. I shiver at the thought of all the potential Eastlands that roam the seas right now.

The Shipyard

Keep scrolling for more images of the SS Eastland rescue operation.