The 15th century found the world in unprecedented upheaval. As the ancient Silk Roads crumbled down with the collapse of the Mongol Empire, the Ottomans pushed for hegemony in the Levant, clashing with Venice for control over the western end of the China trade. With import costs rising fast, a global shortage of silver and gold bullion triggered European nations into a frenzy of maritime exploration and technical innovation. In search of maritime routes to India and China, Spanish fleets scrambled across the Atlantic, only to run into an unsurmountable obstacle halfway through.

Meanwhile, to restore China from prolonged wars with the Mongols, the ambitious Ming Dynasty unlocked an economic boom of unseen proportions, producing silk and porcelain on a scale never seen before. For these desirable goods, however, the Chinese demanded the only currency that Europe was short of – silver. But in one of life’s ironic twists, the landmass that obstructed Spain’s westward access to the Far East turned out to be a giant continent, bursting with precious metals.

Demand from Europe, supply from Asia, money from America – the stage was set for history’s first age of globalization. And it arrived in the holds of the Manila Galleons.

Chaos in the Andes

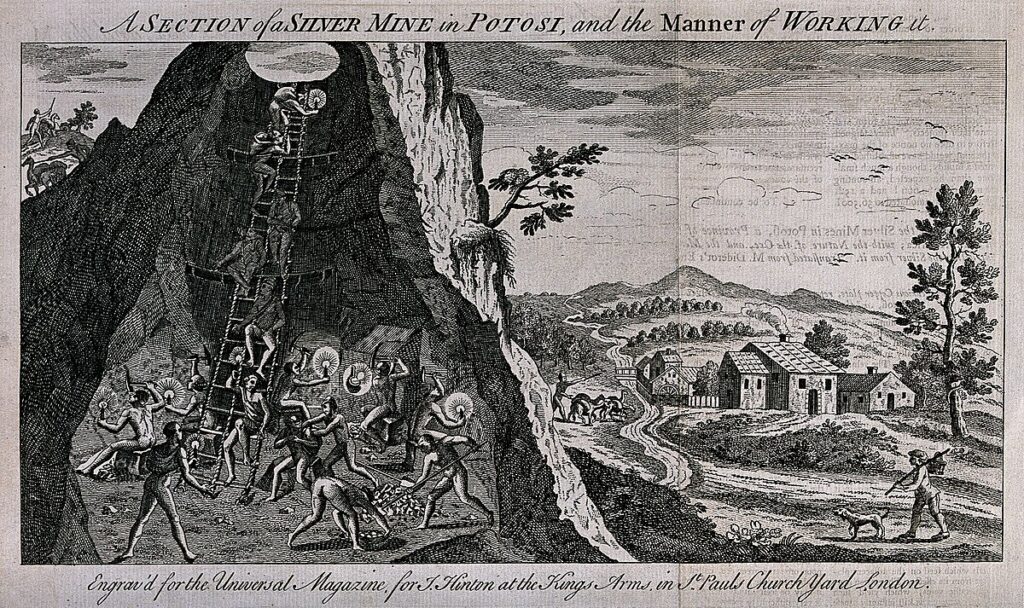

1545 was a strange year for poor Diego de Huallpa. A disillusioned subject of the recently dismantled Inca Empire, his main concern was how to survive the new world order. He knew one thing about his Spanish overlords – their thirst for blood was only exceeded by a ravenous craving for silver.

The Quechua herder, however, was so destitute he had never even seen the precious metal. All he knew were his llamas and the barren slopes of his native mountain. One night, worn out and chilled to the bone, he gathered every twig in sight and lit a blazing bonfire. As he awoke in the morning next to the smoldering ashes, he gasped at the sight. The rocks below had melted into a shiny trickle of pure silver.

The accidental discovery sprouted the mining town of Potosi, which soon grew into the world’s silver capital, churning out almost two thirds of global production. Diego de Huallpa never saw a penny from his discovery.

Buzz in Beijing

Three decades later, on the other side of the Pacific, Zhang Juzheng was struggling with a different problem. Ruling the mighty Chinese Empire on behalf of the adolescent Wanli Emperor, he was obsessed with efficiency, and nothing seemed to vex him more than China’s cumbersome tax system. Since ancient times, the Dragon Throne collected its taxes in rice, horses, and labor. This method had survived for countless centuries, until the Ming’s economic miracle grew China’s population to a quarter of all mankind. Zhang Juzheng’s bold approach to this administrative nightmare was silver.

Don’t forget to visit The Shipyard Shop!

-

The Titanic Guide to the World

9.99 $ -

Dubai Maritime Enthusiast’s Guide

9.99 $ -

Titanic Whiskey Glass

19.00 $ -

Shark Fin Hat

30.00 $

A well-known currency in international trade, silver was not only easily available from nearby Japan and the Silk Route from Europe but also convenient to transport, store, and exchange. Zhang’s grand scheme was to establish it as China’s internal fiscal currency, demanding that all taxes be paid in metal. While undoubtedly efficient, the strategy almost fell apart in the 17th century, when the Shogunate sealed off Japan’s borders, slashing the islands’ trade with China. Amidst the crisis in Beijing, a new lifeline stretched out from thousands of miles across the water – the colossal Andean mine of Potosi.

Philip “Arrives” At The Philippines

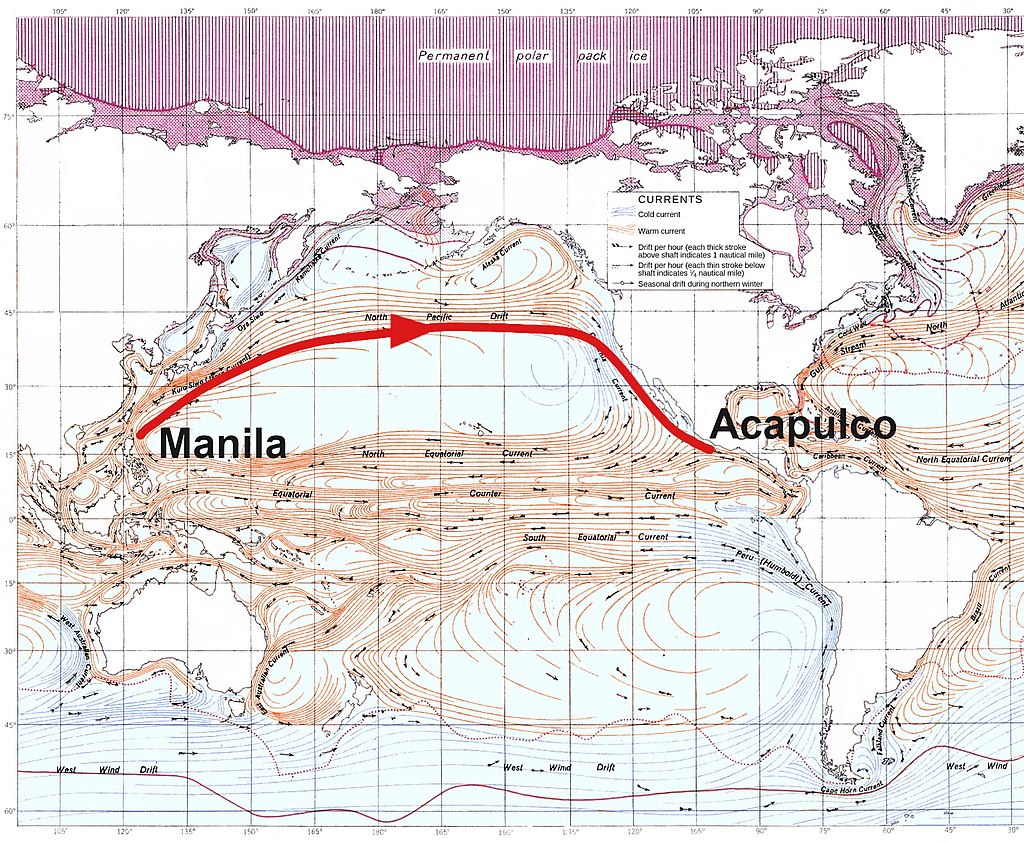

Early summer turns the island of Cebu into a steam bath, and June of 1565 was no exception. But while other sailors complained from the sticky heat, Father Andrés de Urdaneta’s mind was already on the high seas. As King Philipp’s most experienced navigator, he knew that early June was the best time to depart eastward to South America. The problem was he had never done it before.

Until then, the Pacific had only been crossed westward, from New Spain (Mexico) to Japan and China, with all prior attempts for a return journey ending in the notorious Pacific doldrums (now known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone). For Urdaneta, an adventurer-turned-friar, this was to be the challenge of a lifetime.

The galleon San Pedro departed with the southwest monsoon on 1 June 1565, inching through the intricate passages of the archipelago, before turning northeast to seek a favorable current. The mood on board swung between hope and fear, as food and water supplies shrank in the holds. But upon reaching the 38th parallel, a westerly filled the sails, pulling the San Pedro across the ocean. The going was slow and torturous, with sailors falling ill one after the other, until the exhausted, starved, and scurvy-ridden remains of the crew spotted the coast of America.

This crossing closed the last missing link in history’s first truly global trade network, eliminating the final obstacle between the world’s richest silver mine and its largest customer. And as the Spanish and Portuguese empires united in 1580 under the crown of Philip II, so did their maritime routes across the oceans, connecting Europe with Africa, the Americas, and Asia.

The Galleons of Manila

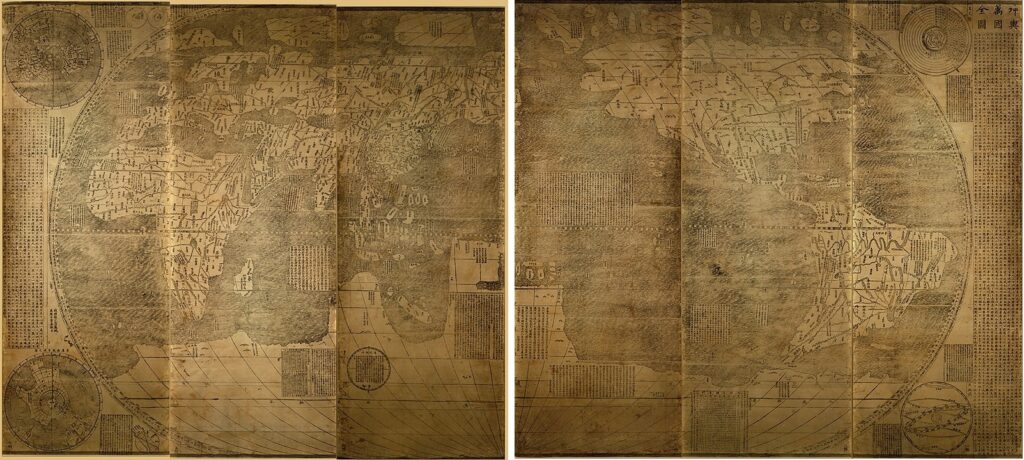

In 1602, Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci kneeled in front of Chinese emperor Wanli, presenting a map of the known world, with the town of Potosi conspicuously marked on it. With his new currency in place, the monarch was reassured by his advisors that nothing could stop the flow of silver from America to China. And as the illustrious ports of Quanzhou and Amoy prepared for the new age of global trade, nearby Spanish Manila was ready and waiting.

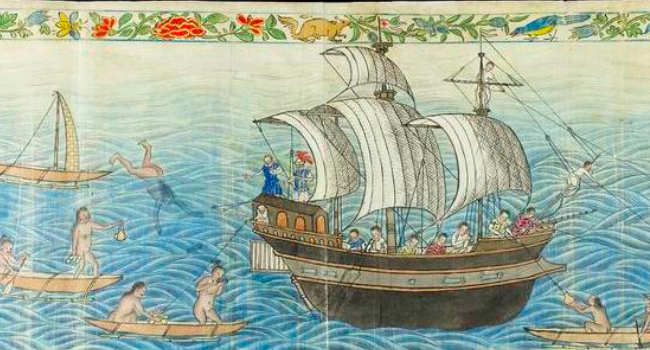

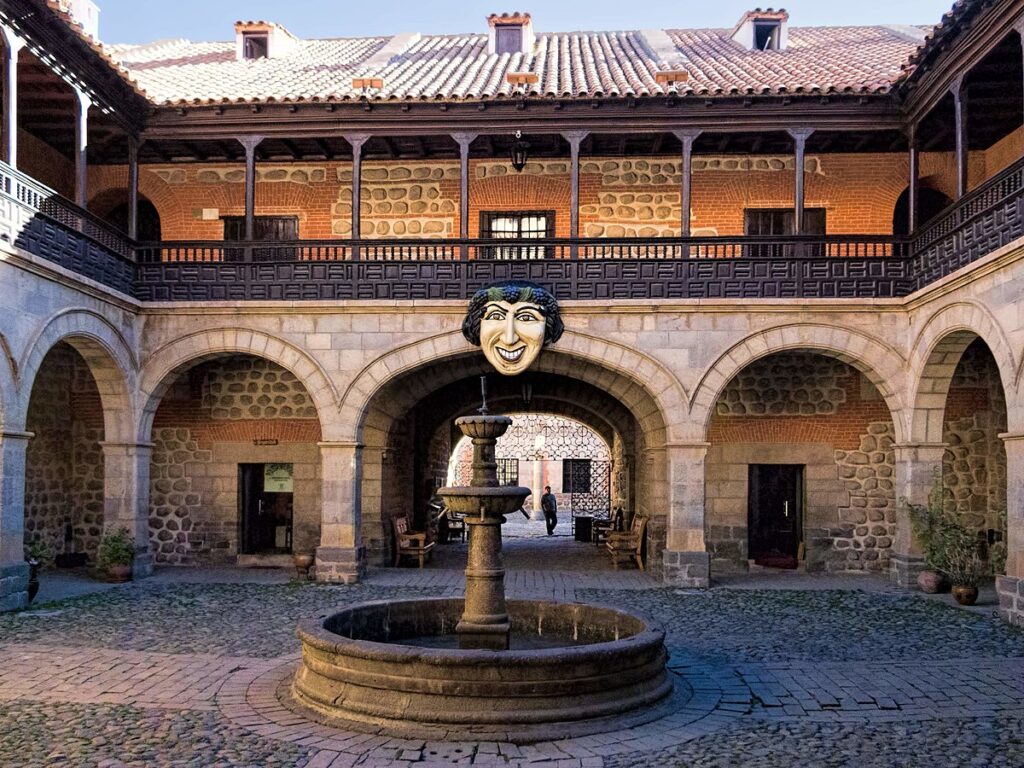

By the end of the 16th century, Manila was a booming colonial capital with stone buildings and a modern port. Southwest of the walled city, in the town of Cavite, the Spanish erected a shipyard destined to build the most magnificent vessels of the time: the galleons. Known as “China Boats” in Mexico and “Acapulco Galleons” in the Philippines, those giant vessels combined the cargo capacity of a carrack with the speed of a caravel. But as the tornaviaje to Acapulco took twice as long as the westbound journey to Manila, both crew and passengers sailed under constant dread: each additional day could cost their lives and a ship brimful of porcelain, silk, and other precious Asian exports.

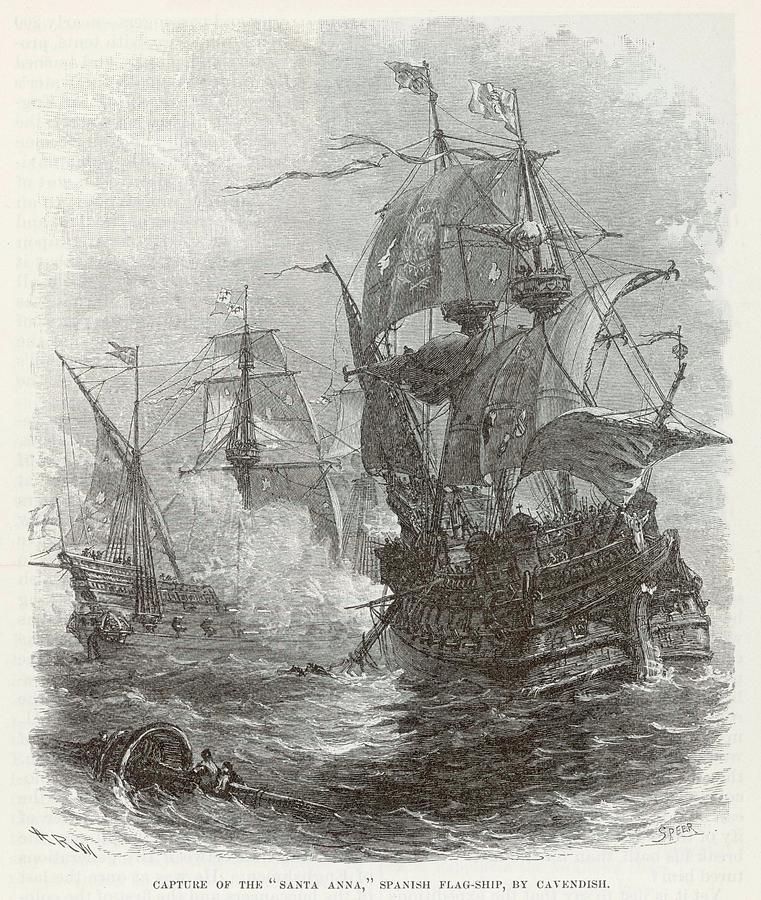

On the westbound journey, however, design and robustness far outweighed the importance of speed. Low-volume, high-density cargoes (like silver bullion) present a huge challenge even for modern vessels, since small miscalculations lead to major imbalances. It only took a few chests of silver shifting in the holds to damage the structure and sink the ship. Thankfully, Spain could supply the best shipwrights, while the Philippine soil grew the most resilient materials. The tropical forests of Palawan offered vast quantities of hardwood, not only resistant to water and parasites but also to foreign artillery. As legend had it, English cannon balls bounced off the hulls of Manila boats – a priceless advantage, considering the numerous attempts by English (later, British) privateers to seize silver galleons over the years.

Large parties of Spanish shipbuilders and indigenous laborers scoured the jungle for months in search of tropical mastwood, apitong trees with their natural water-resistant varnish, or giant myrtle, rich in natural pesticide. Thousands of trees fell for each galleon. Meanwhile, the artisans of Manila worked full-time to sew grand sails from Philippine cotton (renowned for exceptional durability) and spin miles of ropes from the saltwater-resistant fibers of a local banana tree, still known as Manila hemp. The blacksmiths of the walled city used only the best Chinese iron to shape the galleons’ chains, anchors, nails, and pins. The final product was a floating castle, sturdier and more imposing than any other vessel on the high seas.

The major shortcoming of early designs was the clumsy steering through a whip staff near the aft. This technique might have worked fine for the compact vessels of the 15th century, but the small angles of the tiller created severe limitations for the maneuverability of a 500-ton floating fortress, not to mention that the pilot worked like an ox around the clock. In addition, galleons had high hulls, especially at the poop deck, which made loading and cargo distribution a high-precision job. Technological advancement in the early 1700s, like ship’s wheels, unlocked the true potential of galleons, with some 18th century designs reaching the jaw-dropping 2,000 tons.

The Journey

The year was 1693, the place was Naples, and a man called Giovanni Gemelli Careri was suffering a bad case of wanderlust. After a long trip around Europe, the energetic lawyer had discovered a passion for adventure, which made every other occupation unbearably dull. That same year, he put up the shutters of his practice and, life savings in the pocket, boarded a ship to Constantinople. Three years later, he disembarked in Manila with a load of mercury in his bags, hoping to sell it in Acapulco for several times its price in China. To do this, however, the seasoned Italian had to endure the dreaded Pacific tornaviaje on one of the famed galleons.

The crossing began with a slow and excruciating zigzag through the perilous passages of the archipelago – a labyrinth that tested the crew’s patience, wracked the passengers’ nerves, and took a toll on the ship’s provisions. When the galleon finally reached the open ocean, fresh water on board was already running low, and the captain ordered strict rationing. Halfway through, a violent storm exposed the ship’s main weakness, snapping the whipstaff in two like a matchstick – the worst time for an emergency repair. The ship survived by a miracle, but the storm damaged several chests of silk in the hold, dashing their owner’s hopes for a profitable journey.

As the galleon crossed the Equator northward, temperatures dropped fast, and various illnesses struck the famished and exhausted sailors. Passengers were not faring much better, as they received the same meagre, maggot-infested rations and were pestered by the same parasites in the long, freezing nights. When the sentries spotted the North American coast in the distance, after five months on the open seas, the journey was far from over. Just like the painstaking passage through the Philippine archipelago, the final leg to Acapulco was slow and dangerous. The Western coast of North America was notorious among seamen for its stillness, each calm day bringing the tortured passengers one step closer to death.

After 204 days out at sea, Gemelli Careri’s galleon arrived at Acapulco, both crew and passengers weeping with relief. After a spell in Spanish America, the Italian adventurer crossed the Atlantic back to Europe with the Treasure Fleet. His memoire is the only surviving personal account of the grueling eastbound journey.

The Dollar Before the Dollar

Initially, China demanded its silver in the form of sycees, traditional boat-shaped ingots, but advancements in minting technology in Mexico soon made the Spanish dollar (or “Piece of Eight”, referring to the coin’s value of eight reales) much harder to tamper with. As a result, the new currency became so recognizable and widely accepted that countries simply stamped their own assayer’s markings on the dollars, instead of reminting them. In fact, China used the Spanish dollar as de facto currency until 1889, when the Guangdong Mint produced its first “Silver Dragons”. Even then, the Chinese coin used Spanish silver and replicated the specifications of the Pieces of Eight. Mexican dollars remained legal tender in China until the country re-introduced paper currency in 1935.

Ultimately, the rise of global trade and Spanish hegemony in silver production established the Spanish dollar as the first global reserve currency, and it remained so until the late 19th century, when the revolutions in Spanish America struck the final chord.

The End of the Manila Galleon

By the end of the 18th century, the once-glorious Spanish Empire found itself aged beyond recognition. Under competitive pressure from the corporate fleets of London and Amsterdam, the Iberian giant was feeling hopelessly medieval – its economy stifled by feudal monopolies and the political atmosphere heavy with discontent. To make things worse for Madrid, the success of the American and French Revolutions lit up the fuse of Spain’s corrupt and mismanaged colonies.

What ultimately blew up the powder keg was a Corsican gentleman of certain notoriety in the early 1800s. Soon after Spain and France’s humiliation at Trafalgar, Napoleon made a treacherous move against his former naval ally, occupying the Iberian heartland. The ensuing Peninsular War led to Bonaparte’s violent undoing, but Spain too came out in ruins. In less than two decades, most of its transatlantic dominions were independent countries, dismantling the world’s main supply chain for silver bullion and paving the way for the gold standard. The new Spain followed in the footsteps of the British and the Dutch, disbanding the expensive royal convoys in favor of private shipowners.

In 1815, the Magallanes was the last great galleon to anchor at Manila. Her message rang clear – she arrived from Mexico with an empty hold.

The Shipyard