“I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin.” With these grave words, Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced to the British Parliament in 1940 that Allied forces had failed to contain the German invasion of France. The world’s largest empire was bracing for the most terrifying military clash in its history, a fierce fight for survival against the wrath and efficiency of the Reich.

As the two industrial giants unleashed their fury above the English Channel, casualties skyrocketed, devaluing human lives to mere numbers. There was one number, however, that neither side could afford to ignore – the rising incidents of downed aircraft, each one leading to the loss of a pilot, highly trained and hard to replace.

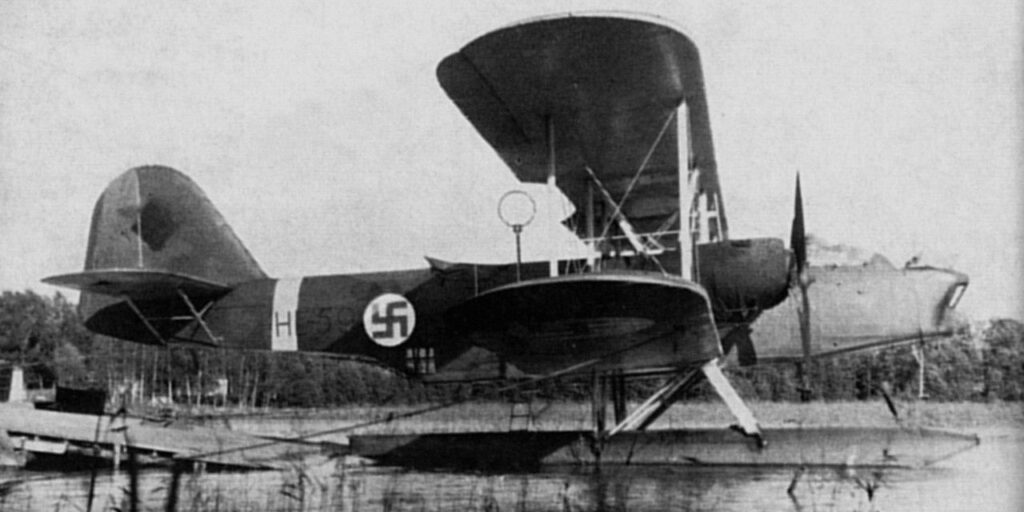

The Germans had it figured out at first, deploying the Seenotdienst on rescue missions with floatplanes, but when London ordered those to be shot down by the RAF, the high command in Berlin had to show some creativity. The result was bizarre and glorious.

The Playful General

The ingenious rescue buoy (Rettungsboje or Udet-Boje) was named after General Ernst Udet, a formidable WWI ace, second only to the Red Baron. Between the wars, the now-forgotten legend drifted between several careers as a stunt pilot, inventor, and a ladies’ man, until the Nazi leadership found him and put him in the worst place for an adventurer of this caliber – behind a desk.

Struggling with mind-numbing bureaucracy and rapacious political games, Udet still made some bold advancements, like introducing dive bombers to the Luftwaffe. Unfortunately, the pressures of war drove the despondent general to alcoholism and suicide, but not before he spawned one last innovative idea – a fleet of 50 fully functional shelters out at sea.

Safe Haven in the Kill Zone

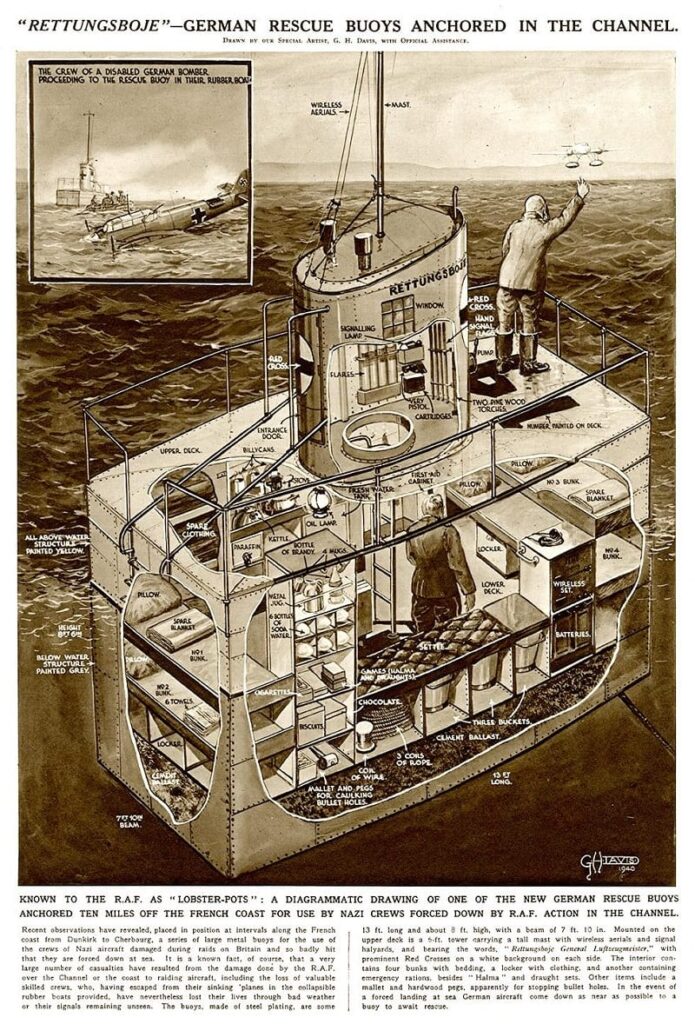

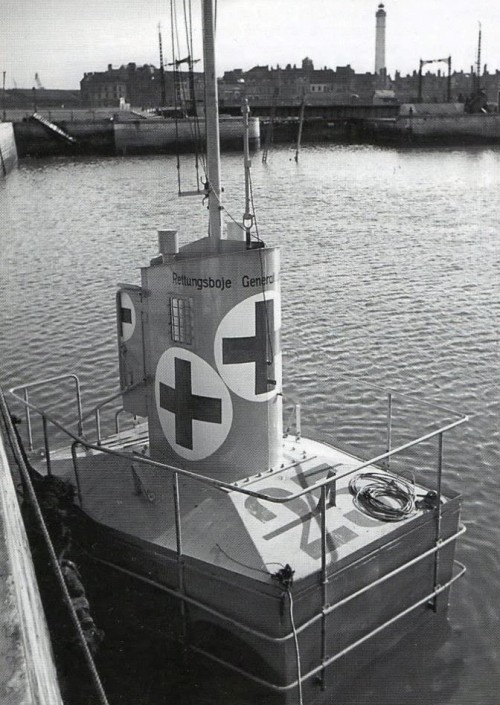

At first glance, an untrained eye could easily dismiss the yellow metal cube bobbing up and down the waves like a giant fishing float. A concrete foundation kept the structure stable in the choppy seas, while a 2-meter-high turret supported a signal mast and an antenna. The deceptive simplicity of the exterior, however, camouflaged a sophisticated facility that could shelter several people, offering more safety and comfort than most places on dry land in those arduous years.

Despite a modest floor space of 4 square meters, the ceiling was 2.5 meters high, somewhat making up for the claustrophobic atmosphere. And although early designs were quite spartan, the improved version had four beds with clean linen, electric lights with kerosene back-ups, first-aid kits, dry clothes, food, cigarettes, board games, and even liquor to fill the lonely, anxious hours. One could also find chocolate in the cupboard – a commodity so rare at the time that many starved troops on the Western Front would have gladly let themselves be downed in the English Channel, just to indulge in the delicacy.

Don’t forget to visit The Shipyard Shop!

Despite the comforts inside, climbing in and out was no easy matter. After the exertions of swimming in icy water, a survivor had to scramble all the way up to the turret and yank the manhole open. Once he caught his breath and took measures against hypothermia, he had to crawl up again and hoist a black anchor ball and a special flag on the mast, letting rescue ships know the buoy was occupied. Red and white beacons signaled in the dark, but those at least could be turned on from the inside, while an automated wireless transmitter broadcasted SOS signals with the buoy’s exact location.

Competition Moves In

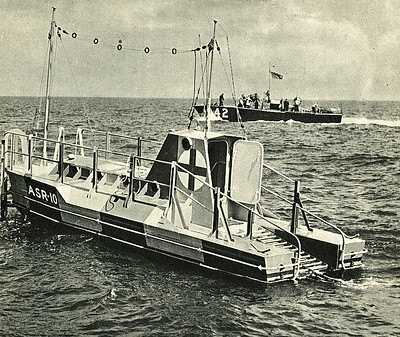

Saving pilots was not a priority exclusive to the Germans, and the British were quick to copy Udet’s idea. The Air-Sea Rescue Float (or ASR) followed the basic principle of the Rettungsboje, with several striking adaptations. Designed by the Carrier company, its hull was shaped like a regular boat, three times the length but only half the height of the German buoy. The extra length allowed six bunks inside, while the low profile made it easier to climb into.

Despite being positioned under the busiest flight paths, the ASR barges were not as useful as expected, being vastly outperformed by the RAF’s rescue launches. The latter picked up more than 13,000 crew and personnel in the course of the war, leaving no room for competition. The Royal Air Force only commissioned sixteen floats, before scrapping the project altogether.

Hanging Around

Eighty years after the last shot of WWII, the good people of Scotland and the Netherlands have lovingly preserved and restored one unit from each model for the benefit of future generations. A German Udet-Boje now stands proud at the Bunker Museum on the Dutch island of Terschelling, while its estranged British relative can be seen and admired at the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine.

The Shipyard