Ah, the Soviet Union – dazzling Mayday parades, heroic cosmonauts, indestructible cars, and luxury cruise vacations…

Wait, what?

Yes, luxury cruises. Despite a well-deserved Spartan image, the USSR never stopped competing against its enemies across the Iron Curtain. And while the Space Race, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the intense proxy wars produced the loudest headlines over the decades, the contest trickled into other, less obvious areas. A master in publicity, the young Communist empire was eager to show the world that a workers’ paradise could exist beyond speeches and pamphlets, and so began the peculiar and captivating Odyssey of Soviet cruises.

Grass Roots

Pleasure cruises in the USSR made a hesitant debut as early as the 1920s, when the charming paddle-steamer Burevestnik plied between Saint Petersburg and the historic island-city of Kronstadt. But on a cloudy August night in 1926, the captain went off on a bender, leaving an inexperienced first officer in charge. While navigating out of port, the officer made a clumsy maneuver to avoid the German vessel Greta, colliding into the granite wall of a nearby warehouse. The Burevestnik sank in the channel, killing at least 60 of the 415 people on board.

Another unfortunate pioneer was the liner Lenin. Built in Gdansk for the Asian and Pacific passenger routes, she survived the October Revolution, only to be nationalized in 1923 and re-purposed as a cruise ship on the Black Sea. It was there that she found her final resting place in 1941, sunk by a mine during the Siege of Sevastopol.

Stalin Sets Sail

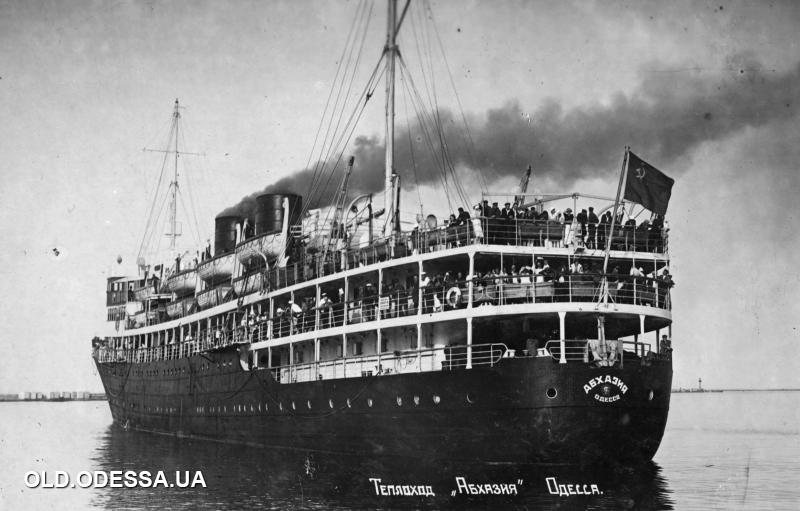

In a century of grand strategists, Joseph Stalin would have made Machiavelli tear up with pride. On a chilly November day in 1930, the cargo liner Abkhazia left Saint Petersburg with 200 merry Soviet tourists on board, plus an army of journalists.

The timing was anything but coincidental. As the Great Depression tore through the global economy, Stalin was sending out a message to the capitalist world – while American workers lined up at soup kitchens, the champions of communism indulged in luxury sea travel. The following year, Abkhazia’s sister Ukraina doubled the PR-effort with another proletarian cruise. And indeed, between 1931 and 1935, some 100,000 disgruntled Americans migrated to the Soviet Union, lured by the country’s industrial boom. But as many of them found a new home in Stalin’s labor camps instead, Soviet vacation cruises were no longer needed and ceased for the next 25 years.

A Cold War in Hot Climates

When Khruschev came to power in 1953, many believed that the USSR was finally about to change tack. Steering away from Stalin’s austere wartime policy, the new leader’s strategy of relative liberalization directed effort and money towards modernization and improvement of living standards. One outcome of these new bourgeois appetites was the revival of cruising.

In 1956, the veteran liner Pobeda left Odesa on a 25-day sightseeing tour of Europe. On board, 423 workers, intellectuals, and functionaries were getting their cameras ready to capture views of Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden. A relic of the interwar period, built for HAPAG’s service to Central America, the vessel had changed owners and names a couple of times, before arriving at Odesa as part of Germany’s war reparations to the USSR. The voyage was a roaring success, giving birth to a thriving industry in the next three decades.

Even though cruises remained an utmost luxury, available to a chosen few, the new leadership asserted its ambitions with the commissioning of their first purpose-built cruise vessels: the 1958 Mikhail Kalinin-class. Although smaller than their Western rivals, the 19 sister-ships made a solid impression at sea and offered comforts unseen on Soviet dry land – luxury cabins, swimming pools, sports facilities, a library, and a night club. The new fleet, built with great efficiency by the Mathias-Thesen Werft in East Germany, proudly sailed around the Mediterranean (Turkey, Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, Malta, Italy, and France) and the Pacific (Vladivostok to Nagasaki).

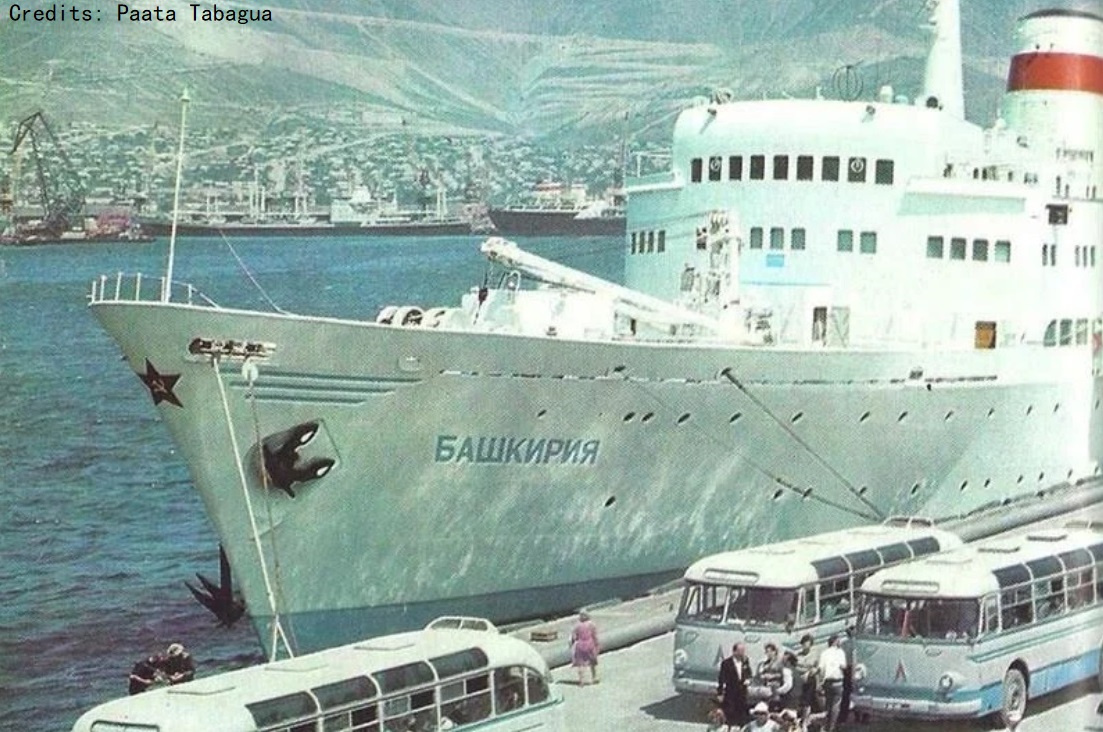

Soviet cruise routes often followed recent political developments, and very few of those could match the scale and dynamics of African decolonization. Between 1957 and 1977, fifty new countries on the continent gained independence from their European overlords, triggering the USSR’s scramble for influence. One attempt to gain a foothold in this new arena was a 26-day cruise along the West African coast on the MS Bashkiriya. It sailed from Odesa to the young and turbulent nations of Morocco, Senegal, Liberia, Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone. As demand for exotic voyages only grew, the MS Litva was launched on an East African route through Egypt, Yemen, Somalia, Kenia, and Zanzibar.

Don’t forget to visit The Shipyard Shop!

But none of these vibrant tropical destinations captivated the Soviet imagination quite like India. Threatened on all sides by belligerent neighbors and struggling with a volatile post-colonial economy, India embraced the Soviet offer for help in key industrial sectors – defense, energy, and steel, among many others. A side effect of this friendship was a new seasonal cruise from Odesa to several picturesque coastal cities on the subcontinent.

Going Global

Having gained significant momentum in the early 1960s, the Soviet Union’s cruise industry took aim at the global market with the Ivan Franko-class. Built by Mathias-Thesen-Werft, this stunning new generation was as capable on the regular transatlantic runs from Leningrad to Montreal as on the seasonal tourist routes. At 176 meters length (577 ft), the vessels accommodated 700 passengers with various degrees of luxury. Over several decades, these masterpieces of the Eastern Bloc formed the pinnacle of Soviet passenger shipping, catering not only to the local elite, but to a diverse audience of foreign tourists.

From the five vessels in the class, perhaps the most illustrious and controversial was the 1972 MS Mikhail Lermontov. As the youngest sister in the family, she was also the most advanced, featuring an indoor swimming pool with a removable glass ceiling, satellite connection, and glass-front boutiques. She entered service on the passenger route Bremerhaven – London – Le Havre – New York, but the Soviet operator soon decided to convert her into a cruise ship for foreign customers. With an aggressive pricing strategy, attracting tourists from all over Europe, she may have grown too popular too fast – Russian sources reported multiple anonymous threats to the captain and a few sabotage attempts. But the blurriest and most disputed episode in her biography was her last voyage.

On 6 February 1986, local pilot Captain Jamison steered the ship around New Zealand’s South Island. Without prompt or explanation, he maneuvered into a notorious narrow channel between Cape Jackson and the Cape Jackson Lighthouse. The result was as shocking as it was predictable – the vessel struck rocks at only 5.5 meters (18 ft) depth and began listing to starboard. It took the liner five hours to disappear beneath the surface, time enough to rescue all but one person on board. Despite numerous investigations and lawsuits, the pilot could never explain the ludicrous maneuver, giving rise to various conspiracy theories. At 12 m depth and near to shore, the wreck of MS Mikhail Lermontov is now a popular diving site.

A Runaway in the Pacific

On a stormy December night in 1974, no one on the SS Sovetskiy Soyuz saw when a passenger jumped overboard into the raging Western Pacific. Three days later, a Philippine fisherman near Siargao Island spotted a foreign man, clinging to a drifting boat for dear life. In the following six months, authorities in Manila racked their brains how to deal with the curious castaway – Soviet defector, illegal immigrant…spy?

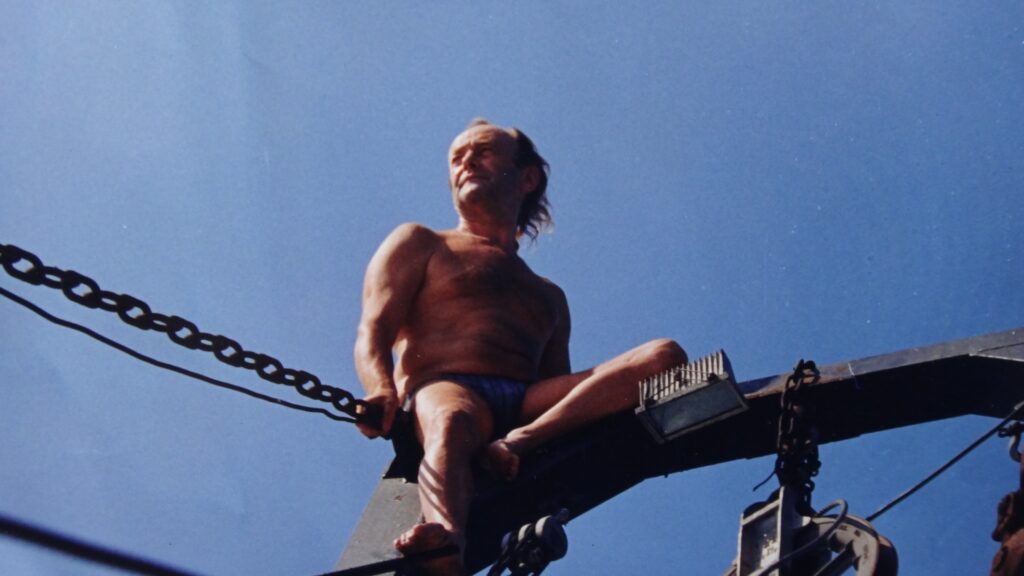

Stanislav Kurilov had always been an excellent swimmer, and no wonder, as the young Russian was among the USSR’s most distinguished oceanographers. He was no dissident, not even politically minded, his only passion being the open sea and its promise of adventure. But right at the peak of his scientific career, Moscow’s bureaucratic cobweb entangled him beyond hope. In 1970, Kurilov arranged two joint underwater projects with the legendary Jacques-Yves Cousteau but was deemed politically unreliable by the authorities and denied travel documents. Angry and disillusioned, he planned a grand exit from the Communist world.

Kurilov booked one of the popular “cruises to nowhere”, an ocean voyage from Vladivostok to the Equator, without stopovers, therefore not requiring passport and visas. The exact route was kept obscure by the crew even after departure, partly because no one on board cared much. In the jolly atmosphere, who would have suspected that Kurilov, a top oceanographer, would know the Pacific like the palm of his hand? Armed with a small-scale map and a pair of binoculars, he made a competent estimate of the ship’s location, choosing a point he believed to be within swimming distance from the Philippine shore.

More form The Shipyard Shop

On the tempestuous night of his “disembarking”, wearing no more than swim briefs, a snorkel, and a pair of fins, Kurilov plunged from a height of 12 meters, almost hitting the ship’s screw for a premature end of the adventure. But the sea must have recognized one of its own, for the storm did him no harm, and neither did the sharks. After three days and two nights, the Russian found himself in a Philippine prison on accusations of unlawful border crossing. Six months later, after several rounds of diplomatic tug-of-war, Kurilov landed in Canada, a free man.

The Soviet Titanic

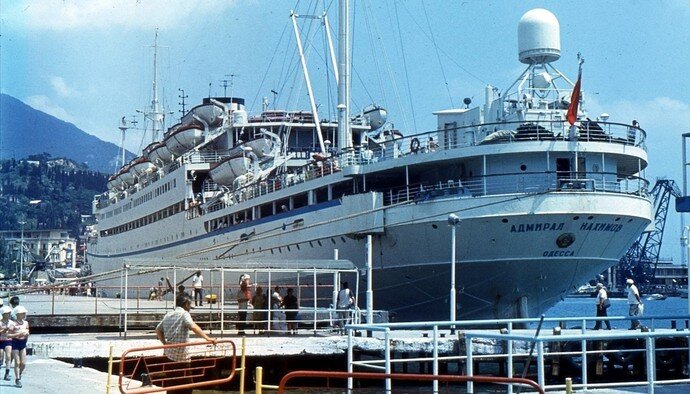

A ship’s name defines her destiny – you never name her after a dead seaman or a sunken vessel. Such sailor’s superstitions sound quirky on dry land, but once the water gets salty, strange forces come into play. They say the dark curse of the liner SS Admiral Nakhimov began in 1897, when a modest cargo steamer, named after Crimean War hero Admiral Pavel Nakhimov, sank in a Black Sea storm. Eight years later, at the height of the Russo-Japanese War, the armored cruiser Admiral Nakhimov was torpedoed to the bottom of the Sea of Japan. During the 1941 Siege of Sevastopol, German aerial bombardment of Crimea sank the light cruiser Chervona Ukraina, originally named (you guessed it!) Admiral Nakhimov. In 1960, a Soviet Navy cruiser of the same unfortunate name ended up as a dummy for missile target-practice.

Such eerie string of omens would have cautioned any sailor, but it is usually bureaucrats who name ships, and when Germany surrendered the mine-struck SS Berlin to the USSR in 1946, the abandoned liner became yet another Admiral Nakhimov in the ill-fated line. Accounting for her age and damage history, she entered service in the Black Sea, doing short cruises between Odesa and Batumi.

It was on one of these voyages on 31 August 1986, when she gracefully departed from Novorossiysk en route to Sochi with 888 passengers and 346 crew. Minutes later, the pilot detected 18,000-ton bulk carrier Pyotr Vasev, heading straight on a collision course. After a heated exchange of warnings and assurances on the radio, the crew on Pyotr Vasev agreed to change course as needed.

Only they didn’t.

The captain of the freighter retired to his quarters without giving further orders, and the second mate did nothing until the last moment, when it was too late. The Pyotr Vasev rammed the Admiral Nakhimov’s starboard at an almost 90-degree angle, tearing a giant hole in the hull.

Contrary to regulations, all cabin windows were open in the stuffy summer night, which accelerated the intake of water and made the list too strong for lowering lifeboats. With lightning speed, the crew threw 32 life rafts into the sea, saving many passengers, but hundreds of others jumped into the water with any floating object they could grab in the dark. The SS Admiral Nakhimov sank in seven minutes, taking 423 passengers and crew with her.

Tectonic Shifts

Many Soviet cruise ships were destined to outlive their colossal motherland. When the reforms of the early 1990s brought an end to the formidable Communist stronghold, most ships from the Ivan Franko and Mikhail Kalinin classes were auctioned off to buyers from all over the world.

The most jaw-dropping was the story of SS Aleksandr Pushkin of the Ivan Franko-class, which changed several owners over the years, including the Norwegian Cruise Line. She made regular voyages to Southeast Asia, Africa, and Antarctica as recently as 2020, when her owner went bankrupt amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and sent her to the scrapyard in Alang. India.

Another curious fate was that of SS Bashkiriya, veteran of the 1960s West Africa route, which capsized in the port of Bangkok in 2006, remaining half-submerged in the Chao Phraya River for several years and attracting photographers from across the globe.

Ironically, it was from sensational news like this that many Russians found out about the existence of Soviet cruise ships. In all three decades of their glamorous history, those charming overseas voyages were never made available to the general public.

Missed last week’s post? Click here!

The Shipyard