The recent decade has been grimly generous with humanitarian catastrophes, and while recent history abounds with natural disasters, man-made ones have often surpassed them in destructiveness. But looking further back in time, the Holocaust still sits at the top of this dark list – an endless source of tragedy and heroism. This story is about the ships that set off on a mission to save European Jews from the fire-breathing jaws of the Third Reich. Some made it, others perished together with their passengers.

Kindling the Fire of Destruction

Following the Ottoman defeat in the Great War, the British Mandate in Palestine opened the door to the anxious Jewish diaspora in Europe. But when the local Arab population revolted in the late 1930s’, London settled for a compromise, reducing immigration quotas to a fraction of the actual demand. Meanwhile, the persecution of Jews in Europe was heating up fast, and while many looked towards the USA as the ultimate haven, America proved to be less than welcoming. Thus squeezed from all sides, some Jewish refugees illegally boarded ships and set off on uncertain, perilous, and sometimes deadly journeys.

Setting Sail

The Vallos was a small steamer, hired in 1934 to transport 350 illegal Jewish migrants to the Palestinian shore, where they eventually received permission to disembark. The move sparked serious controversy at higher political levels, with many Jewish activists fearing that such unsanctioned ventures could threaten the fragile position of Jewish settlers in Palestine. Nevertheless, the success of the Vallos (and the lack of other options) compelled others to take the uncertain sea route.

Daring early voyages included the Parita with 700 on board, the Naomi Julia (1,200), and the Tiger Hill with 1,205 migrants. All three vessels sailed from Romania, through the Black Sea, and along the Levant toward Haifa. They barely made it. Threatened with repatriation, the Parita’s passengers sabotaged the ship, in order to beach her and avoid being returned. When the Naomi Julia was apprehended by the British Navy in the Mediterranean, despair drove passengers to pour out their drinking water and inflict enough damage on the vessel to alarm the British and force them to allow docking at Haifa, where all men on board were dispatched to detention camps in Palestine. The Tiger Hill’s journey was even more distressing, when a British gunboat opened fire, killing two passengers.

Resistance to Jewish migration promised to remain rigid, but so did people’s ingenuity. As Greek ships were prohibited by law to transport illegal immigrants, many vessels in the country changed their registry to Panama. In a 1939 report to the US Secretary of State, the American consul at Jerusalem provided a long list of Greek ships, suspected of having switched their port of registry for the purpose of smuggling refugees. Parita, Naomi Julia, and Tiger Hill were all on the list.

A Hero’s Quest

The troubled Jewish exodus in the pre-war period culminated with the harrowing voyage of the HAPAG liner MS St. Louis. Built by the Bremer-Vulkan Shipyards in Bremen, she was 574 ft (175 m) long, with a beam of 72 ft (22 m), and had 16,732 gross registered tons. Serving both as a transatlantic liner and a cruise ship, the St. Louis at least offered a safe and comfortable journey to her 937 unfortunate passengers, the result of Captain Gustav Schröder’s efforts to treat the refugees with the necessary dignity.

What the passengers did not know was that the voyage was doomed before it even began. Poverty, unemployment, and the rise of right-wing movements in Cuba had triggered mass protests against the country’s liberal immigration policy, forcing President Federico Laredo Bru to revoke all issued landing certificates a few days before the St. Louis departed Hamburg. But although this meant most refugees on board no longer had valid visas, the Hamburg America Line was anxious to get rid of them and said nothing. The liner sailed for Havana on 13 May 1939.

Upon arrival, the Cuban authorities allowed only 22 Jewish immigrants to enter the country – the few fortunate ones in possession of US visas, guaranteeing their onward journey. The rest remained in port, shocked and wondering if they would have to face ultimate demise in the hands of the Reich. And as negotiations between various Jewish lobbies and the Cuban Government fell through, Captain Schröder took things in his own hands. Determined not to return a single passenger to Germany, his first destination was Florida, where both he and some of the passengers pleaded with the US Government for admittance. The White House remained silent.

Canada was next enroute, but with similar results. Anti-immigration sentiments prevailed among the political elite, forcing Schröder to steer the St. Louis back across the ocean. Docking at Antwerp, the passengers waited anxiously as negotiations heated up between Jewish organizations and European Governments, with international media showing more and more sympathy with the plight of the refugees. Eventually, all passengers were given asylum in Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. 254 did not survive Nazi occupation in Europe.

Disasters at Sea

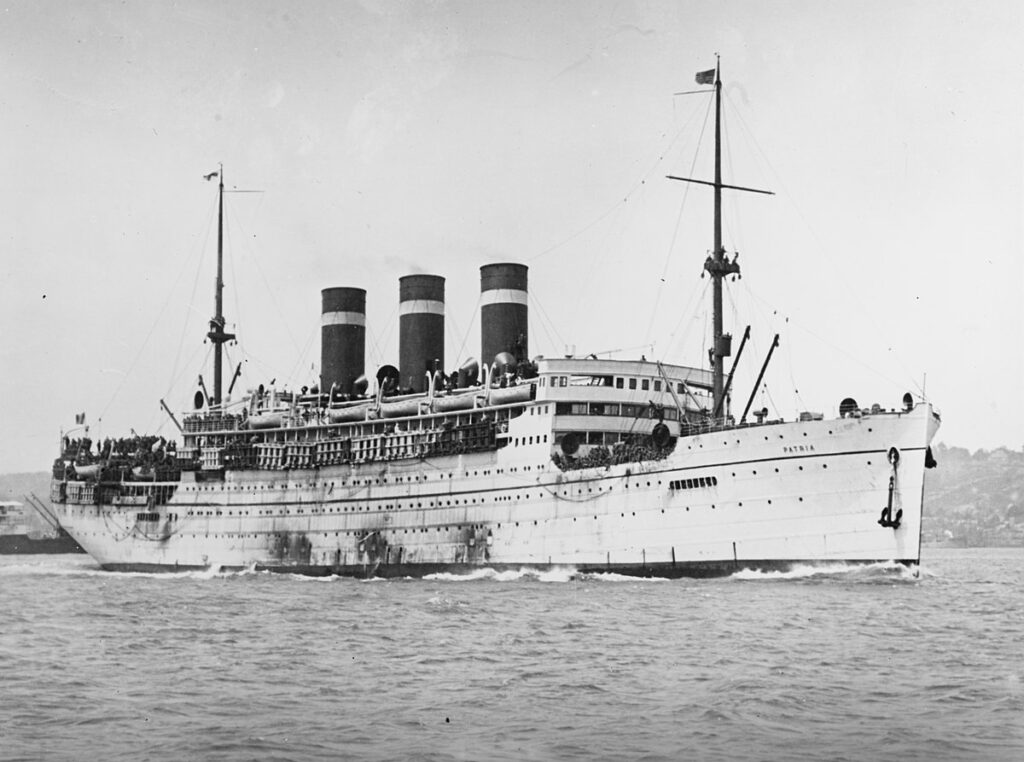

One affair in the early years of World War II caused much tragedy and frustration. In October 1940, three rusty old steamers arrived in Haifa from Romania. The Pacific, the Atlantic, and the Milos (all built in the 1800s) carried more than 3,400 Jewish refugees on board, most having fled Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia on river boats down the Danube, before boarding the three small steamships at Tulcea. However, the immigrants received the usual cold reception by the British authorities, who decided to board everyone on the former French liner Patria for deportation to the island of Mauritius.

Pressed for time, the Haganah (Jewish paramilitary organization and predecessor of today’s IDF) came up with the audacious plan to smuggle a bomb onboard the Patria, small enough to cause only technical damage and prevent the ship from leaving port. But improvised explosive devices tend to be unpredictable, and the detonation on the morning of November 25th blew such a large hole in the hull that the Patria sank within a quarter of an hour, killing 260 people. The rest were either allowed to stay in Palestine or suffered deportation to Mauritius on other vessels.

Later that year, the sailboat Salvador became an outrageous example of what despair does to people. Setting out from Varna with 352 immigrants on board, she was supposed to be towed to Istanbul, but the Bulgarian tugboat Voevoda only hauled her out to sea and left her to the elements. Another tug was urgently sent out of Istanbul, where the Salvador and her passengers waited five days, before being once again towed out and left adrift. Without any adequate equipment at his disposal, the captain made one final attempt to sail back to Istanbul, but the overloaded vessel ran aground near Silivri and literally fell apart. 238 people, of which 66 children, died from drowning or hypothermia. Only a few reached the shore to receive first aid from local residents.

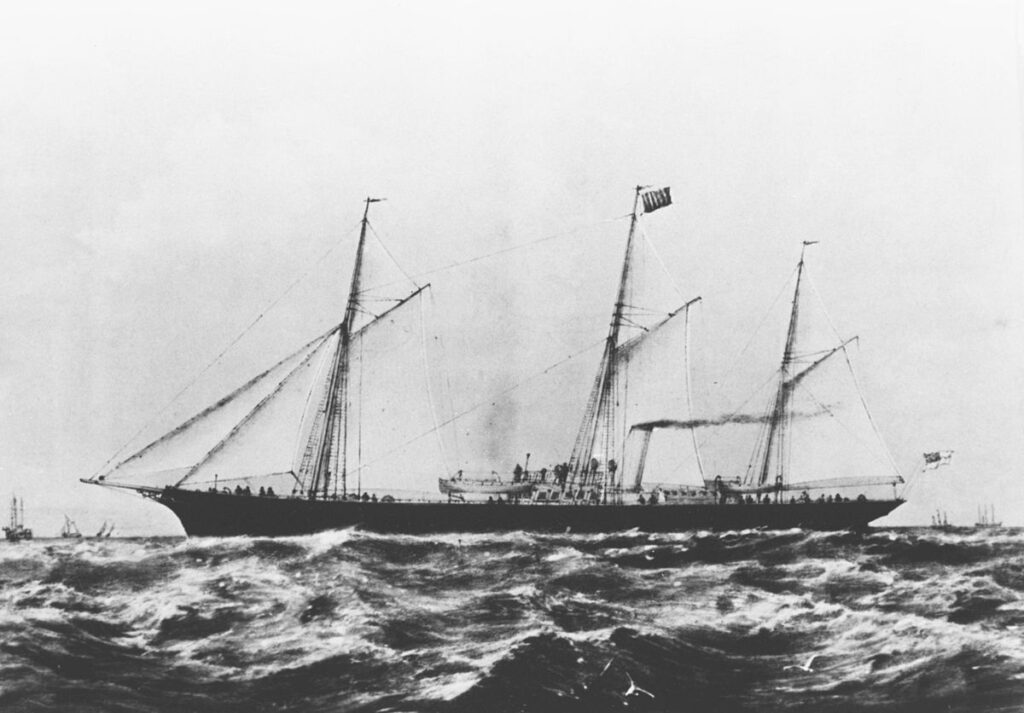

A year later, a moldy wooden-hulled steamer was purchased by a Bulgarian Zionist to transport nearly 800 illegals from Romania to Palestine. Ironically, the Struma was built in 1867 as a luxury yacht for a British royalty, but by 1942 she was so dilapidated that the rattly old engine gave up near Istanbul, and the ship had to be towed to port. After 70 excruciating days of abortive diplomacy between Turkey and Britain, the refugees were refused permission to sail on to Palestine. The coast guard towed the Struma out in the open sea, leaving her adrift. As the desperate passengers called out for help at vessels passing by, a Soviet Shchuka-class submarine mistook the Struma for an Axis troop-carrier and torpedoed her. Only four people survived the attack, one passenger and three crew members.

A similar fate befell another wooden-hulled old wreck – the Turkish Mefküre, with 320 souls on board. On 3 August 1944, she and two other steamers in pitiful condition sailed from Constanța in Romania south toward the Bosphorus. This was no underground affair – the trio had official permission from Germany and was accompanied by Romanian naval vessels – but this did not prevent another Russian Shchuka-class to machine-gun the unfortunate Mefküre to shreds. All but eleven people on board perished in the deep waters of the Black Sea.

Post-War Struggles

A failure in itself, the 1947 journey of the SS Exodus may have accelerated the establishment of the State of Israel the following year. Built in 1928 as President Warfield, she was sold for scrap in 1946, and then resold to the Haganah, who invested large sums of money to turn the old vessel into a veritable fortress of illegal immigration. When she finally left Sète for Palestine with 4,500 Jewish immigrants on board, the Exodus boasted formidable defence contraptions – barbed wire around the bridge and engine room, netting around lower decks, as well as improvised “canons” that could spray steam and hot oil to discourage takeover by British personnel.

Nearly half of the passengers were in turn “armed” with fake passports and visas to help them leave the shores of France. But hoping for smooth sailing would have been groundless optimism for the battered refugees – from the moment they left the pier, they were shadowed by British warships, determined to prevent the Exodus from reaching the coast of Palestine. And when a British fleet surrounded the rusty vessel in Palestinian waters, Haganah agents on board prepared for battle. In the ensuing scuffle with the boarding party, two passengers died of gunshot wounds and one crew member was clubbed to death, while dozens suffered various injuries.

Upon arrival in Haifa, the remaining passengers were sent back to internment camps in occupied Germany. With nothing left to lose, they began hunger-strikes to attract attention from the press, and as the news triggered protests all over Europe, public opinion turned a more-sympathetic eye toward Jewish refugees. In the aftermath of the scandal, the British Government felt embarrassed enough to accelerate the process of recognizing the State of Israel in 1948.

The Shipyard

A part of the thousands of tragic stories of human suffering in the WW2, told with empathy and warning about the misfortunes that befall us again.

Thank you The Shipyard

Thank you for reading it!