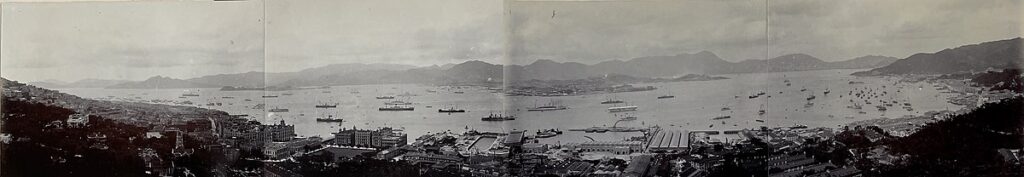

The 20th century brought more prosperity and turbulence to Hong Kong, as the adolescent colony matured to become Asia’s leading commercial, logistical, and financial hub. The port was no exception – with the hegemony of steam and (later) diesel, the city’s maritime and shipbuilding industry boomed, serving as an industrial role model for an entire continent. With the establishment of Communist China in 1949 and the ensuing trade restrictions, the island’s strategic importance as a Cold-War entrepôt soared to new heights. But being a geopolitical hotspot came at a price. Troubles never gave Hong Kong a moment of peace – a legacy that haunts the Fragrant Harbor to this day.

Arrested Development: The Naval Dockyard

The Naval Dockyard, like many great things in Hong Kong, made a humble start. In 1858, the Royal Navy carved out a priceless little plot from the coast, but only managed to build a single rudimentary pier for a victualling yard. The tai pans, outraged by the Navy’s intervention in the profitable land market, raised (legitimate) concerns that a shipyard would become another choke point for the already busy traffic. As a result, the dockyard’s development stalled over the next forty years, with only sporadic extensions in the aftermath of the Second Opium War.

Public opposition to the yard was so strong in the 19th century that the Navy was forced to expand into the sea. When full-scale construction of the dockyard finally began in 1900, the new dockyard had to be a floating basin, requiring massive land reclamation with complex dredging operations. Due to space restrictions, an old troopship (the iconic HMS Tamar) had to serve as the Royal Navy supply base from 1897 all the way to 1941, when it was scuttled during the Japanese invasion. For decades after WWII, the Royal Navy buildings were still referred to as HMS Tamar.

A half-century of turmoil kept the dockyard busy. Even when the Japanese armies advanced through the New Territories on 8 December 1941, the docks were still in operation, with the gunboat HMS Moth and Motor Torpedo Boat 12 still in for repairs. Two gunboats, HMS Scout and HMS Thanet were also docked at the yard but managed to escape to Singapore.

By the end of the war, Asia’s political landscape was changed forever, and Hong Kong’s Naval Dockyard was no exception. With Britain surrendering its role of global naval hegemon to the USA, the empire downsized its Pacific Fleet, cutting down the Hong Kong Naval Shipyard staff by more than a third in 1948. Nine years later, the Government announced its ultimate decision to close down the facility by 1959, putting an end to an era and giving the city its contemporary landscape.

The Golden Age of Shipbuilding

Many early trading houses in Hong Kong flourished on drug profits – after all, these were the people who convinced London to wage Opium Wars – but the tai pans’ black money also fertilized multiple legitimate industries. And while Jardine Matheson and Swire were by far the most illustrious names in the new colony, more relevant to the city’s maritime glory were their shipyards – the Hong Kong and Whampoa Docks and the Taikoo Dockyard.

As was often the case back then, the Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company (HWD) was incorporated by an alliance of astute Scotsmen – watchmaker Douglas Lapraik and P&O agent Thomas Sutherland, under Jardine’s patronage. In 1864, the new dockyard became the first registered limited company in the colony. The second was Lapraik’s Hongkong, Canton, and Macao Steamboat Company.

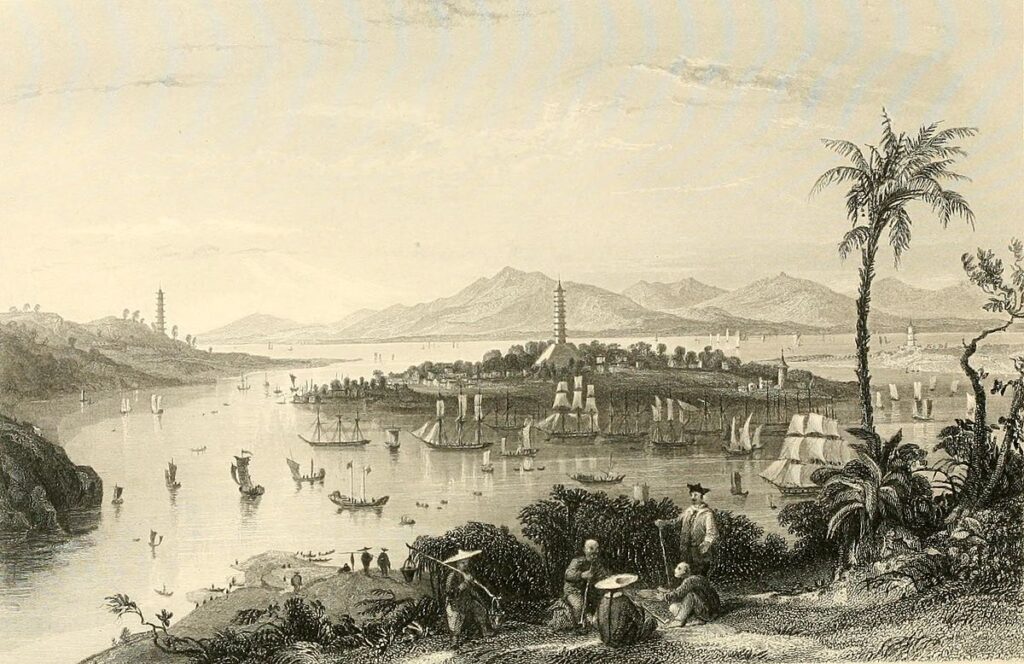

The roots of the yard went back to the 18th century Canton system, when Guangzhou had a monopoly on China’s foreign trade. Europeans could only sail as far as Whampoa Island, where they built warehouses and rudimentary docks for small craft. As trade intensified after the First Opium War, P&O took an interest in the strategically located island, sending Scotsman John Couper in 1845 to build a graving drydock in place of the old mud docks. When Couper disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 1856, his son managed the yard until Lapraik and Sutherland took over.

From these humble beginnings, the HWD grew to become Asia’s leading shipbuilder. In 1865, the company bought the stone-clad Lamont Dock in Aberdeen, then built the Hope Dock two years later, and amalgamated with the Union Dock Company in 1870. Ten years later, with the first land reclamations in Kowloon, the HWD constructed its famous Cosmopolitan Dock. By the turn of the century, the newly formed giant had supplied numerous vessels for the bustling China trade, establishing itself as an industry leader. With the onset of the Great War, the HWD received commissions for several larger vessels, including the 8,000 DWT War Bomber and War Trooper. But these achievements were the zenith of the shipyard, as it soon began to lose market share to a fierce new competitor.

John Swire made his name powering the Yangtze River trade with his paddle steamers. In 1872, in partnership with White Star’s William Imrie and Thomas Ismay (yes, Bruce Ismay’s father), Swire founded the China Navigation Company, expanding the business from 2 to 29 vessels by 1894. As business grew, Swire’s sons and partners were eager to have a dockyard for the fleet’s maintenance, but the man himself opposed the idea until his death in 1898.

With resistance out of the way, the company soon began construction near Swire’s sugar refinery at Quarry Bay. Fighting formidable resistance from HWD, the new dockyard made a slow start, producing their first vessel as late as 1910. In the following decades, though, Taikoo often made the headlines with the largest steamers build in British overseas dominions: the 1917 Autolycus (441ft, for Alfred Holt), the 1924 Anhui (350ft, for the China Navigation Company), and the 1939 Breconshire (508ft, for the Glen Line).

Intense rivalry between the two shipbuilders raged until the 1970s, when rising competition from Japan forced them to negotiate for peace. In 1972, the Hong Kong and Whampoa Docks merged with the Taikoo Dockyard, forming the United Hong Kong Dockyard. The envisioned economy of scale, if not glorious, proved immensely profitable. As the new conglomerate concentrated its operations on Tsing Yi Island, the Kowloon plots were turned into a giant residential complex. Today, the only trace of the famous dockyard is a beautiful ship-monument in the Whampoa Garden housing complex.

A Star (Ferry) is Born

Britain’s acquisition of Kowloon did not create immediate demand for connections across Victoria Harbour – due to the peninsula’s sparse population, boat services in the first twenty years were sporadic and decentralized. But when construction began on the new Kowloon Wharf, Parsee merchant Dorabjee Nowrojee bought a British-made steamboat, setting up a daily shuttle for construction workers across the harbor. As the business grew, Nowrojee purchased three more boats to establish the Kowloon Ferry Company as a regular service to the public. The four vessels were named Morning Star, Evening Star, Rising Star, and Guiding Star, so the company’s renaming to Star Ferry after Nowrojee’s retirement did not surprise anyone.

Over the course of a century, the Star Ferry remained Hong Kong’s most permanent feature, evolving from simple steamboats to diesel-electric double-deckers. The wharves have been reconstructed several times, from the original wooden jetties to today’s iconic twin-pier structures.

From Ruin to Renaissance

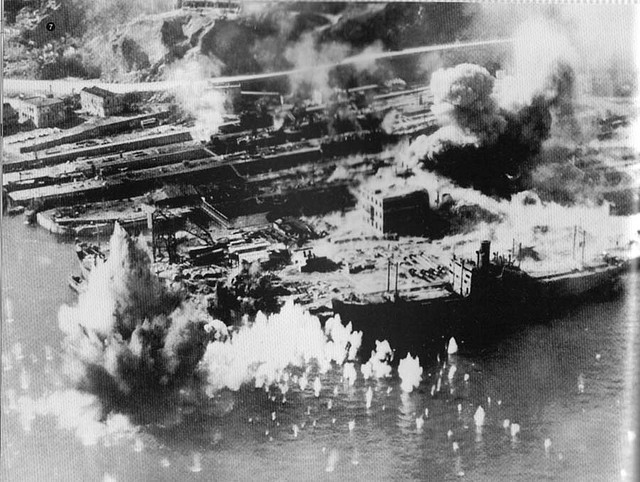

On 25 December 1941, Britain surrendered Hong Kong to the Japanese. The invasion destroyed much of the port facilities – dockyards, wharves, warehouses, quays, as well as numerous vessels at port. Records show that the Star Ferry continued operation under heavy bombardment, evacuating troops and civilians from the advancing Japanese forces. The occupation suspended the service for the next four years, the longest interruption in its history.

Even though the Japanese restored some facilities for repair and maintenance, the Allied bombing from 1944 onward turned the port back into a wasteland. Japan surrendered on 15 August 1945, leaving the British Government and millions of tormented Hongkongers to rebuild the city from ruins. Ignoring the severe shortages of food, medicine, and energy, the colonial government made a push to rebuild the port as the fastest way to revive the economy, but despite some early signs of life, Hong Kong’s industry remained crippled for years.

Following Mao’s 1950 intervention in the Korean War, Western nations implemented a trade embargo against China. Forced to comply, Hong Kong lost a major trading partner, while a wave of Mainland refugees surged toward the colony, putting even more weight on the fragile economy. After a decade of turbulent economic and social restructuring, Hong Kong turned away from entrepot trade and toward manufacturing of textiles and plastic goods. As a result, shipping and shipbuilding entered a new golden age, with the number of vessels entering the port growing threefold from 1949 to 1966.

This upturn was followed by large-scale investments in the port infrastructure: lighthouses and signal stations, typhoon shelters and moorings, a world-class ocean terminal with adjacent tourist facilities, as well as several new piers with modern logistical facilities. 1966 saw the completion of a cruise terminal in Kowloon, able to accommodate two large ocean liners or four smaller cruise ships.

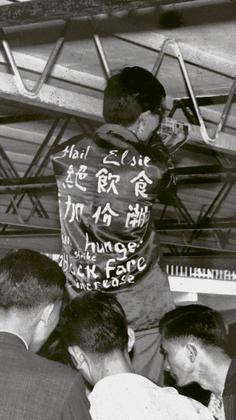

But the 1960s were not all smooth sailing. Industrial growth also led to rising inequality, which not only irritated the local population but also served as a convenient sabotage weapon for Communist China. By 1966, public discontent needed little more than a spark to flare, and the spark happened to be the Star Ferry ticket price. A peaceful demonstration against rising fares escalated to full-blown riots against racial inequality, corruption, and housing shortages. The clamp-down was nothing less than brutal, with nearly 2,000 arrests, dozens injured, and one fatality.

And as the Cultural Revolution raged across the border like a forest fire, a second outburst in Hong Kong was only a matter of time. 1967 saw even larger and more violent upheavals, leaving 51 dead, 832 wounded, and 1,936 convicted of various crimes. This time, though, the government grudgingly offered a package of economic and social reforms.

Sea Monsters: The Age of Container Shipping

Another trend, this one external, joined the Government’s long list of concerns in the late 1960s. With vast potential for efficiency and economy, containerization was taking over the global shipping industry. The problem was that ports required heavy investment before jumping on the lucrative bandwagon, but the colony’s most abundant resources were enterprise and courage. By 1976 Hong Kong had completed its first five container terminals at Kwai Chung, equipped with cutting-edge management software with real-time data on arrivals, departures, and container location. For most years between 1987 and 2004, the city was the busiest port in the world, competing against Western giants like New York and Rotterdam.

Return to the Middle Kingdom

With the expiry of the 99-year lease of the New Territories, the UK agreed to relinquish the entire colony back to China in 1997. Under the policy of ‘one country, two systems’, Hong Kong retained a special administrative status, reaffirming itself as a commercial link between the PRC and the West. And with China’s stupendous economic growth in the following decade, the city saw massive capital inflows from its new master, resulting in further expansion of the port and its surrounding infrastructure. The increasing quantities of Chinese cargo through Hong Kong led to the commissioning of a ninth container terminal in 2005 on Tsing Yi Island, with capacity of 2.6 million TEU per year.

But manufactured goods were not the only commodity on the rise. With the global boom in cruise tourism, the Ocean Terminal at Tsim Sha Tsui could no longer handle the soaring number of leisure vessels, with many cruise ships forced to berth around the container port. Opportunity was knocking at the door, and Hong Kong was not going to ignore it – with the retirement of the legendary Kai Tak Airport, the Government used the land to build a new cruise terminal with enough capacity for two 1,200ft vessels.

An Uncertain Future or Business as Usual?

Since 1841, Hong Kong has not had a single day of peace and quiet, yet it has managed to survive and prosper despite numerous challenges. With the transfer of sovereignty back to China, many claim that the ‘glory days’ are over, but this cheeky little island has heard it all before. Despite losing the lead among container ports to modern behemoths like Shanghai and Singapore, Hong Kong still holds a unique trump – an uninterrupted tradition of enterprise going back almost two centuries. This is what the Mainland lacks, and the Chinese have come up with a grand strategy to capitalize on the city’s unique spirit.

With almost 1% of the world’s population, the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Greater Bay Area (GBA) is now the largest megalopolis on the planet. The project unites South China’s largest ports – Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong – responsible for 37% of China’s exports and 12% of the country’s GDP. Guangzhou is the manufacturing powerhouse, Shenzhen is the IT capital, while Macao serves as a link to Europe, Brazil, and Southeast Asia. With its global heritage, Hong Kong remains the region’s international hub for finance, transportation, and services. Does this seem like the end? Let us wait another 100 years before we answer this question.

The Shipyard

Missed the first part? Click here!