The sea is a treacherous mistress – an alluring caress of winds and waves, below them only silent death. She has called out countless eager lovers throughout the ages, only to swallow them in her dark, bottomless waters. But some return to haunt us – a lost ship reemerges without the crew; a sunk vessel reappears in port; a ship that never was comes to life. Tales of the sea have been around since the dawn of sailing – some true and others less so – but all fascinating to our imagination.

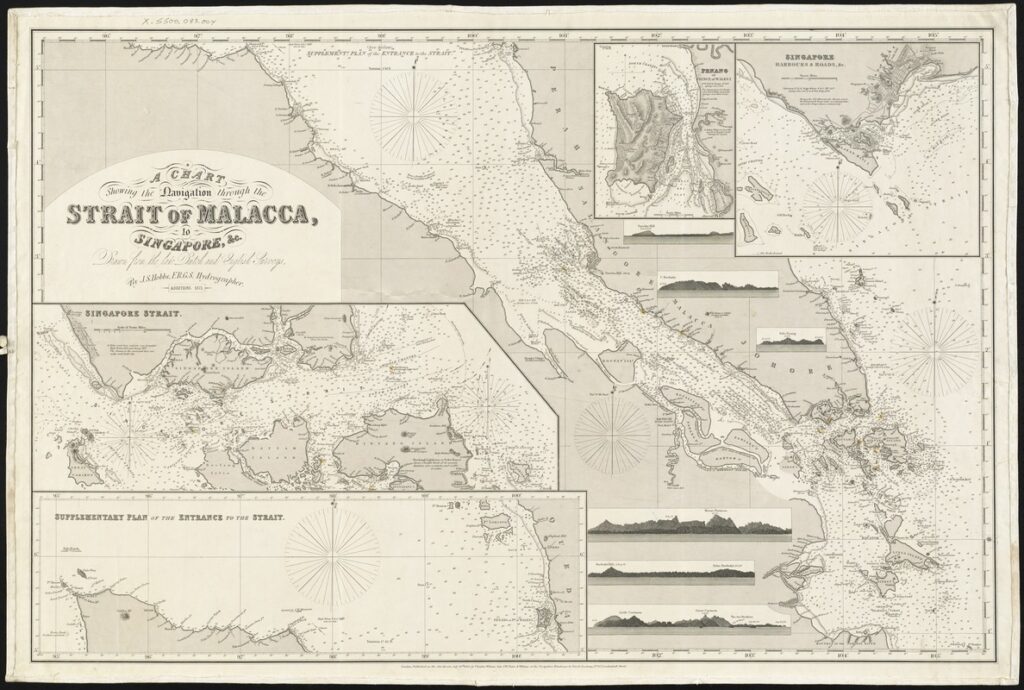

The year 1947 saw the world healing from a devastating war and getting ready for another, cold one. Southeast Asia, recently liberated from Japanese oppressors, was now eager to also shed its European colonizers. The rising tensions attracted naval presence from multiple nations. Dutch ships were among the most common, as the small European power sought to restore its massive colonial interests in what later became Indonesia. Hence, when a US Navy vessel at the Straits of Malacca intercepted a distress signal from a Dutch steamship, the American crew could not have been more shocked by the grisly events that unraveled.

One officer later recalled:

“We were about 200 miles south-west of the Solomon Islands when we intercepted the following signal: ‘SOS from the steamship Ourang Medan. Beg ships with short wave wireless get touch doctor. Urgent.’

With our short wave set, we relayed the call for help. Medical stations in Germany, Rome, and France replied. We informed the Ourang Medan and asked her to transmit her request. The Ourang Medan replied with its auxiliary transmitter: ‘Probable second officer dead. Other members crew also killed. Disregard medical consultation. SOS urgent assistance warship…’

At the end of 16 hours, we sighted a big ship on the horizon. It flew no flag, was listing slightly to the starboard, and the propeller motionless. From our bridge we could see it was the Ourang Medan…We launched two lifeboats with eight men in each and rowed across to the Ourang Medan and boarded her. Bodies of sailors were lying about on the deck. We could find no sign of a wound on any of them. Death seemed to have taken them by surprise at their posts. On the captain’s bridge we found the body of a second officer. We counted 12 bodies, three of them of deck officers, but we reckoned the Ourang Medan should have had a crew of about 40.”

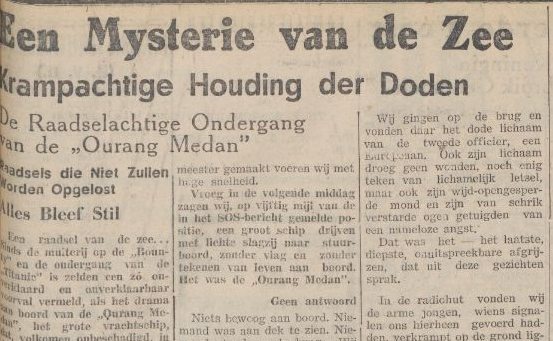

Another record of the gruesome story came out in a 1952 edition of the US journal Proceedings of the Merchant Marine Council:

“Perhaps one of the most perturbing sea dramas occurred in February 1948. Radio silence was broken with an urgent S. O. S. from the SS Ourang Medan, a Dutch vessel, then proceeding through the Straits of Malacca. The strange distress call, transmitted in Morse Code, eerily read, ‘S. O. S. from Ourang Medan * * * we float. All officers, including the Captain, dead in chartroom and on the bridge. Probably whole of crew dead * * *.’ A few confused dots and dashes later two words came through clearly. They were: ‘I die.’ Then, nothing more. Later the Ourang Medan was found adrift approximately 50 miles from her indicated position. When the vessel which had stumbled across her sent a boat over to investigate, the sailors swarming aboard the Ourang Medan found a sight seldom seen. There wasn’t a living person or creature on board. There were dead men everywhere. Bodies were strewn about the decks, in the passageways, in the charthouse, on the bridge. Sprawled on their backs, the frozen faces upturned to the sun with mouths gaping open and eyes staring, the dead bodies resembled horrible caricatures. Even the ship’s dog was found dead. Yet, the bodies seemed to bear no sign of injury or wounds.”

The American vessel is said to have been the Silver Star. The captain gave orders to tow the Dutchman back to port, but just as the sailors secured it, a fire broke out in one of the Ourang Medan’s cargo holds, forcing the Silver Star crew to cut the lines. The ghost ship exploded shortly after and sank.

No evidence of the wreck was found, but no one ever bothered searching for it either. More interestingly, despite numerous sources reporting the ill-fated steamer, records show no registry under that name. So what killed the crew of a ship that didn’t formally exist?

Ten days after the incident, a lifeboat with six corpses and one survivor washed up on the Marshall Islands. The survivor, Jerry Rabbit, claimed to be the second officer of the Ourang Medan. To his astonished savior, a missionary on the island of Taongi, he told an extraordinary tale of conspiracy, horror, and betrayal.

Rabbit was recruited in Shanghai, with no checks to his qualification or background, to work on a former Chinese steamer. What he first thought to be a stroke of luck, however, soon turned into an alarming mystery – after leaving Shanghai under the name Ourang Medan, the vessel took on some 15,000 crates of unknown cargo at various Chinese ports, before taking course for Costa Rica. The observant second mate had no doubts left – this was a smuggling operation.

Soon after loading the secret consignment, Rabbit heard stokers and machine staff complain of stomach cramps and fatigue. He duly informed the captain, only to be dismissed and rebuked. When the illness claimed its first victim, the captain recorded the cause of death as heart attack, something which Rabbit considered unlikely. With his suspicions on the rise, the sailor sneaked a peek into the ship’s logbook, which listed items like sulfuric acid, cyanide, and nitroglycerin, the first two being much more likely causes of the now increasing death toll on board. A survivor by nature, Rabbit did not wait around to be the next victim. He stole the logbook from the captain’s cabin, jumped into a lifeboat with six other men, and fled. He alone survived the tortures of a long and agonizing drift on the open ocean.

Jerry Rabbit died a few days later, reportedly of exhaustion, leaving the missionary as the only pair of ears to have heard his remarkable adventure.

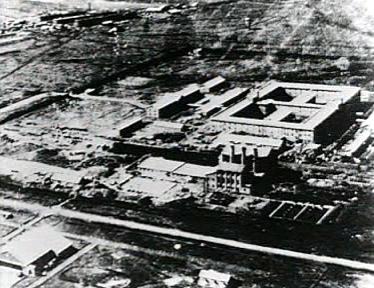

But how much water does this story hold? The mystery of the Dutch steamship has been told time and again, the theories as numerous and untraceable as the sources. Some call it a conspiracy, others an urban legend. Its credibility is further eroded by inconsistencies in the very basic facts. One source, for example, places the incident in 1940, claiming that the Ourang Medan, a camouflaged old tramp, was in fact transporting chemical warfare agents for the notorious Japanese Unit 731, which would explain the ship’s absence from any records. No mention of the Ourang Medan has survived in the Silver Star’s log, no harbor admitted having the shady steamer in port, no shipyard seems to have built her.

And yet, detailed officers’ accounts from the Silver Star and the Marshall Islands missionary have been circulated by various media for many years. In addition, one cannot help but ask why the appearance of Jerry Rabbit in a boat with six dead men was never followed by an investigation. And, by the way, whatever happened to that logbook? If the missionary was diligent enough to report the story, he must have had the good sense to preserve the logbook as the only material evidence.

The question remains – a real horror-story, or a mischievous sailor’s yarn? You decide. Happy Halloween!

The Shipyard

P.S. If you love a good story about a ghost-ship mysteriously washing up on shore, you may also enjoy reading about the SS Morro Castle!

oh my what a gripping story and one for someone to think very hard about, I most enjoyed the part about it being a ship carrying supplies to the Japanese and not being registered for that purpose alone and that does also explain the reason no one logged it on the ports logs.

i for one am not sure if the ship was real no one can really tell but in a way if it was they would probably want to stray as far from the ship for safety reasons.

but again we might never know the real truth behind this ship and probably never will.

So glad you enjoyed it!