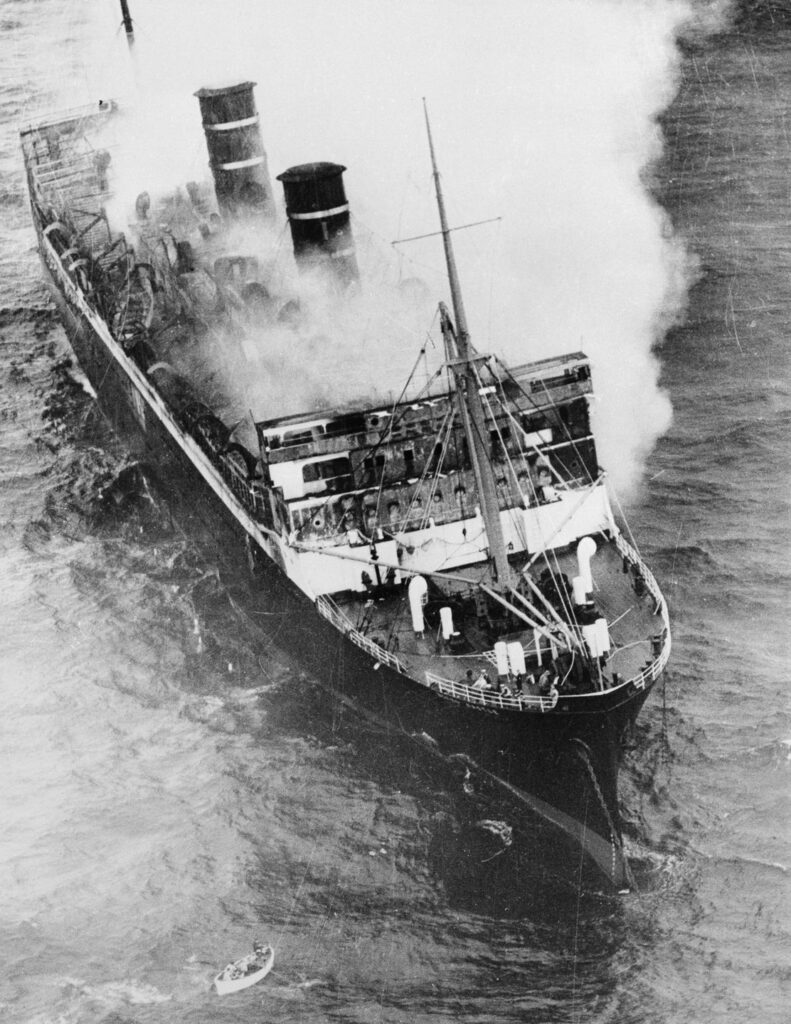

In the dark hours before dawn on 9 September 1934, the residents of Asbury Park, a seaside town in New Jersey, woke up to a gruesome spectacle. A passenger ship, entirely engulfed in flames, approached through the darkness like a ghostly flare and washed up on the shore. But the agonizing wails and desperate cries for help of the dying didn’t reach through the distance, swallowed instead by the roar of a storm. Up close, though, the wild flames illuminated a horrible scene of people jumping into the water, only to drown in the powerful waves. Just hours earlier, this grisly conflagration had been one of the most luxurious passenger ships in the world. The SS Morro Castle – a floating palace of fun – sailed between New York and Havana with a select group of wealthy passengers on board.

Built for the Ward Line in the unfortunate year 1930, the ship was 154.8 m long, 21.6 m wide, and had a tonnage of 11,520 GRT. She could carry a total of 532 passengers (437 first class, 95 tourist class) and 240 crew, and was generously equipped with 12 lifeboats for up to 800 people. Together with her sister ship, the SS Oriente, she was the largest and most commercially successful ship the Ward Line had ever built.

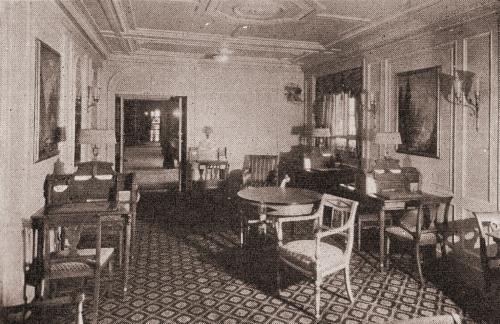

In contrast to the simple and practical style prevailing on cruise ships at the time, the 16 suites and 142 cabins of the Morro Castle exuded luxury and elegance. The five decks boasted cutting-edge equipment, such as telephones, elevators, and the latest heating and ventilation systems, in addition to the ship’s other amenities, like a gymnasium, a day-care, a library, and the expected choice of bars. The largest room on board, a pastel-colored dining room, stretched over two decks, while the First-Class lounge was a fine composition of wood panels, mother-of-pearl inlays, and Corinthian columns. The most fortunate of the passengers enjoyed its cozy atmosphere around a fireplace, with a piano playing in the background.

Despite the rough economy, the Morro Castle was fully booked out on most of its journeys, proving particularly popular with wealthy customers in need of a break from the oppressive sobriety of the Prohibition. The destination: Havana, a Caribbean hot spot with abundant, cheap alcohol and legendary nightlife. In fact, the thirstiest and most impatient passengers didn’t even have to wait until they reached the palm-lined coast of Cuba – they were served alcohol as soon as they set foot on board, making the rest of the journey one wild, roaring party.

So, what went wrong?

In short, everything. It all started on 7 September 1934, while the ship was returning from Havana to New York. Captain Robert Wilmott complained of an upset stomach after having dinner in his cabin, and a few hours later he was found dead in the bathroom, apparently having suffered a heart attack caused by food poisoning. The body was laid out in the cabin for a more detailed autopsy in New York, and Chief Officer William Warms took command.

It was a tradition that a formal captain’s dinner and dance should take place on the last evening of every trip – the social highlight of every crossing. On that evening, however, the death of the captain was announced to the passengers, and the festivities planned for the night were cancelled. The drinking and dancing, however, continued in many of the cabins and common spaces.

While passengers made the best of a spoiled party in the last hours before arrival in New York, the weather outside had taken a turn for the worse. With enormous waves lashing against the hull, the ship rolled from side to side. Perhaps a little sobered out by the jolts, a passenger in the smoking room approached the steward on duty, Daniel Campbell, stating that he smelled smoke. Following a search at three in the morning, Campbell discovered a fire in one of the locked cupboards of the first-class writing room on Deck B. Confident that such a tiny smolder would soon be put out, passengers did not bother leaving the smoking room.

But the fire spread to the carpets, then to the wooden paneling and door frames, from where it blazed out into the hallways, eventually reaching the decks. The paint of the decks and railings flared up in an instant, making it impossible to hold on to anything. The strong wind from the ongoing storm ignited the fire further, from the superstructure all the way down to the hull. As the corridors and stairwells filled with thick smoke, making orientation and breathing difficult, the glass windows in the halls and promenade decks began to burst, raining down on the fleeing passengers. As survivors later reported, the entire ship turned into a torch in a matter of minutes.

Instead of giving orders to lower lifeboats immediately, the new captain wasted time trying to beach the ship. To make things worse, he failed to keep the panicked crew under control, many of whom were inexperienced sailors, hired as cheap labor during the depression. According to George Rogers, radio operator of the ship, the captain gave no orders to send out an S.O.S. signal, nor were any instructions given to passengers, many of whom were already asleep in the cabins that would soon turn into deathtraps.

Those who didn’t suffocate in their sleep, rushed to the stern, gathering into a disorderly crowd – a fatal mistake, as the strong wind drove flames and thick clouds of smoke towards them. The crew ran to the bow to lower the lifeboats, but the davits and chains were stuck. The late Captain Wilmott had recently ordered the crew to repaint them several times, and now six boats remained in their places, useless. The other six drifted away almost empty, as the fire in the mid-section of the ship prevented passengers from reaching the bow. The six lifeboats, with capacity for 408 people, paddled away with a mere 85, almost all of them crew. It was a death sentence for the ones they left behind.

Then the power went out. Fire burned through the cables, causing a blackout all over the ship, and as the engines failed, the Morro Castle was left drifting in the storm. With no help from the crew, no light other than the deadly flames encroaching ever closer, and no other hope for salvation, passengers began to climb the burning railing, plunging one by one into the sea. Deck chairs, lifebuoys, and lifejackets were thrown overboard as swimming aids for the people down there, but the giant waves got to them first, crushing bodies against the side of the ship, the heavy sea swallowing them in its depths. Many passengers broke their necks as they fell in the water – nobody had shown them how to put on a lifejacket correctly, while others landed on objects or on other people, sustaining injuries that lowered their survival chances almost to zero. In a rush to save lives, some men grabbed women and children, throwing them overboard, but most of them drowned without so much as a scream. A few survived the jump as if by a miracle, only to die later of exhaustion from hours in the water.

Rescue Attempts

Although the Morro Castle was very near the shore of New Jersey, the heavy seas prevented rescue vessels from reaching the site early on, and it was well after dawn, when the first of them approached the burning ship and started taking on survivors. By that time, some passengers had even swum all the way to the coast, where the lifeboats lay stranded on the New Jersey beaches. Many of the rescued later stated that crew members had simply paddled by, ignoring their cries for help.

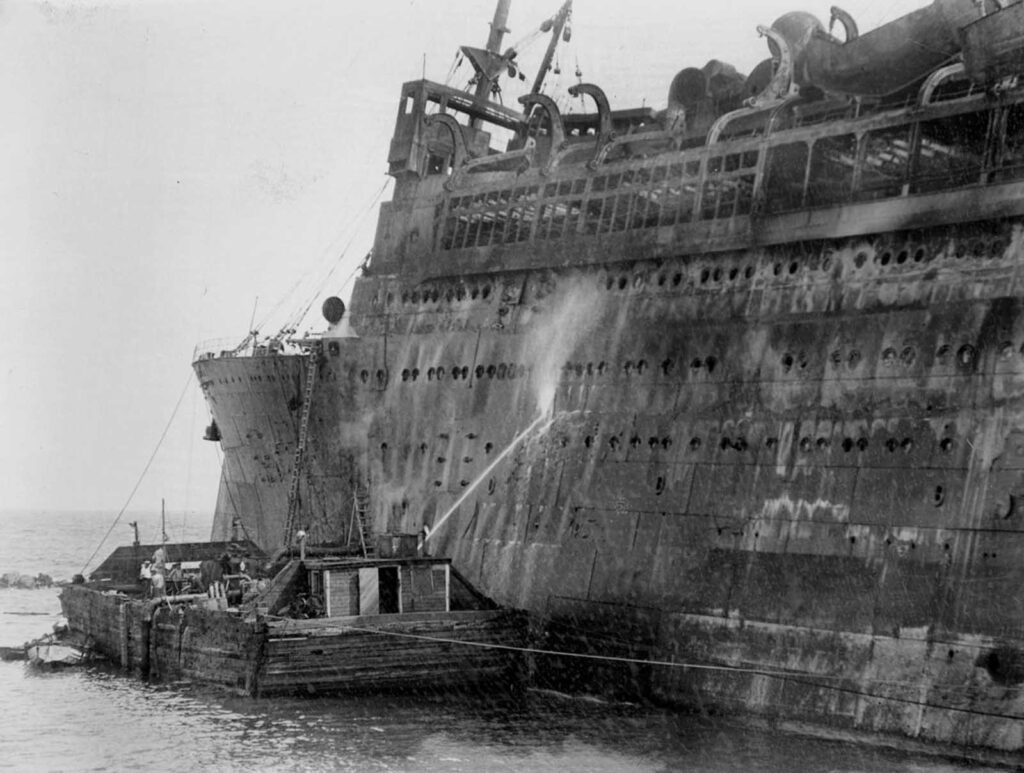

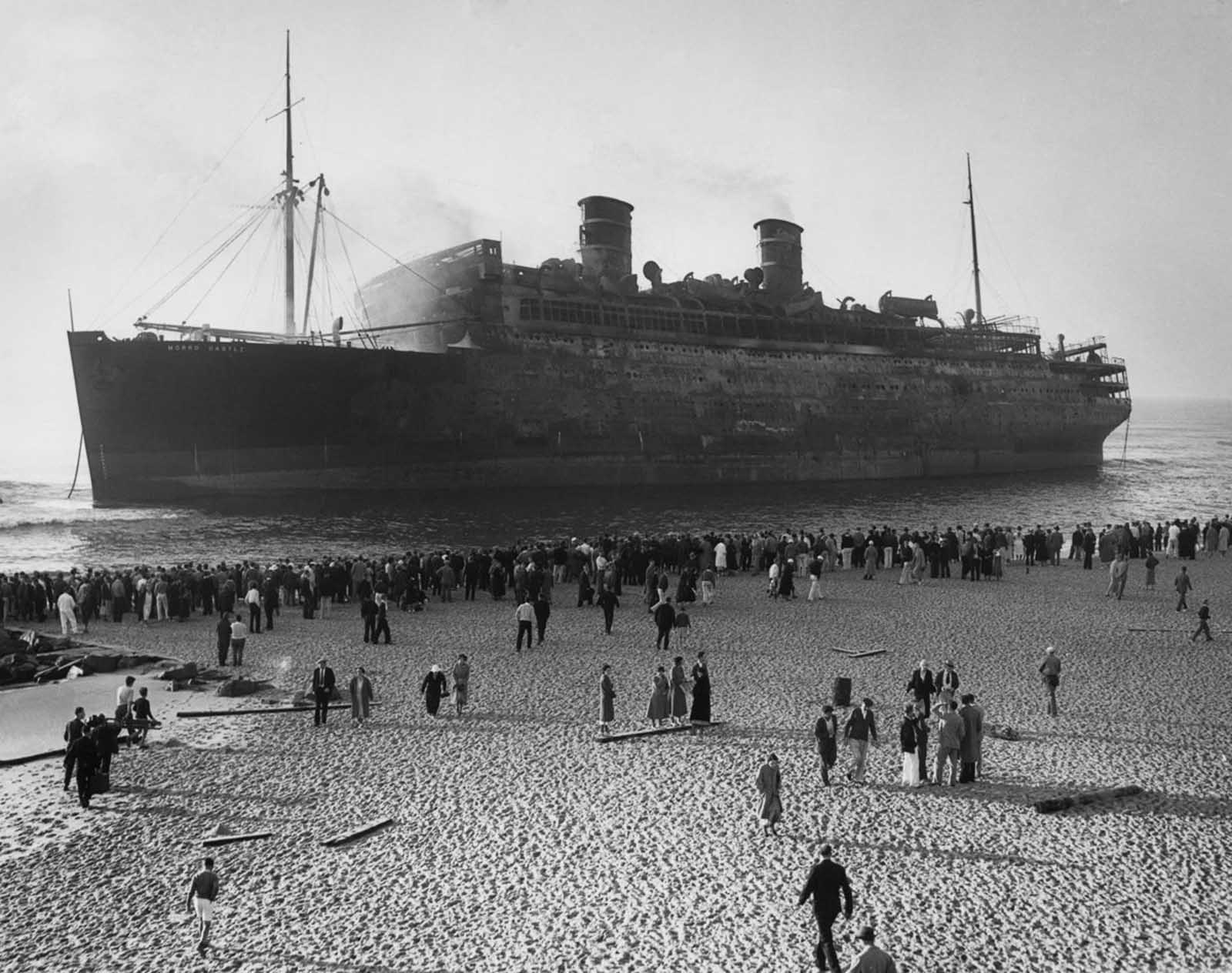

Finally, in the afternoon of 8 September, the black carcass of the SS Morro Castle ran aground in Asbury Park, where locals watched it burn for two more days.

Of the 549 people onboard the liner, 137 were officially reported dead, most of them passengers. The death toll, however, may have been higher, as ships at the time often took illegal refugees who made the crossing to the USA as stowaways. Rumors spread around that dozens of Cuban children, whose parents had sent them off to a better life abroad, perished in the fire.

In the months that followed, the wreck became a tourist attraction and a destination for excursions, bringing back to life the souvenir shops, most of which had closed in the economic recession. On 14 March 1935, what remained of the Morro Castle was towed away, but some accounts say that she sank on the way to the scrapyard.

Mysterious Causes

The cause for the fire was never identified, or at least never shared with the public. In fact, the entire investigation into the Morro Castle incident was kept a little too secret for a passenger ship. Shortly after the tragedy, the aforementioned radio officer, 33-year-old George Rogers, was hailed as the hero of the disaster, having taken it upon himself to send a distress signal despite not being ordered by the new captain. He had remained at his desk until the last possible moment, for which he was celebrated by both public and media.

Later on, however, it was discovered that Rogers had a long criminal record, that included theft, fraud, and, curiously enough, arson. It turned out he was specialized in building explosive and flammable devices, while his medical records stated that he had repeatedly received psychiatric treatment for his antisocial personality disorder.

On the evening before the fire, Rogers had met with Captain Wilmott shortly before the latter had felt ill. The captain having had no prior health problems that could be linked to cardiac arrest, suspicions arose that he could have been poisoned by Rogers. Interestingly, the body of the captain was lost on the way to the morgue, where it was to be tested for poisoning.

Following the Morro Castle disaster, Rogers opened up his own radio repair workshop, which, after a period of financial difficulties, caught fire and burned to the ground. Somewhat ironically, his next job was with the Bayonne Police Department, where he was overheard talking about the Morro Castle fire and sharing specific details about how it started. One of his colleagues, Officer Vincent J. Doyle, became suspicious that Rogers would know such details, considering he was in the radio room at the time, and began to interrogate him. Rogers knew that Doyle was digging up evidence and attempted to murder him by placing a homemade explosive device in a box on the man’s desk. Doyle was seriously injured, but survived the explosion, and spent the rest of his life trying to prove Rogers guilty of the fire.

Rogers was sent to prison for attempted murder but was later released. In 1954, he committed a double homicide in his neighborhood for financial reasons and was sentenced to life. He died in custody on 10 January 1958, of a cerebral hemorrhage. His file was lost.

Rogers was never investigated as a suspect, even though evidence was present, but this was not the only puzzling fact around the Morro Castle incident. The ship’s crew and Captain Warms, despite having been convicted for negligence, had their sentences overturned shortly after the court’s decision. All this, in addition to Captain Wilmott’s mysterious death on the night of the fire and the suspicious circumstances under which Rogers later died in prison, all lead to a speculation that there might have been something about the Morro Castle that the government was trying to hide. But what?

It is worth noting that radio operators at the time were not hired by the shipping line but by the government. Could Rogers have been collecting intelligence for the authorities? Or was he simply an embarrassment to keep away from the public, as nobody had bothered doing a background check when he was hired for the job? And aside from whether Rogers was guilty, why did the government put so much effort into keeping the files classified?

Some claim that Washington used the ship to supply arms to Fulgencio Batista, despite President Roosevelt’s official statement that the United States would not be supporting the 1933 coup in Havana with arms. The ship’s plans were also classified, hinting that they may have shown loading compartments used for the arms. Furthermore, shortly after the court had found the crew of the Morro Castle guilty of negligence, the president overruled the court’s decision, setting the crew free. Did he pardon them in exchange for their silence? If the speculations are right, it is only logical that the government would fear social outrage from public funds being spent on international intrigue, in a time when so many Americans were jobless and hungry.

Conclusion

As with most things buried in the past, we will never know for sure who started the fire on the SS Morro Castle, and why the details of that tragic night are kept so well-guarded to this day. What we know is that many innocent lives were lost due to the incompetence of those responsible for the safety on board. The only positive thing that derived from the tragedy was that it lead to new safety regulations on US passenger and cruise ships, including the use of less flammable materials, a regular mandatory inspection of fire-fighting equipment, and the introduction of emergency drills and safety briefings for all passengers prior to every trip.

The Shipyard

P.S. Do you enjoy ship mystery stories? Read about the ghost ship ‘Ourang Medan’ here!

What a mysterious tragedy! And such a shame, the tragedy always finds innocent people… Amazing article, thank you so much for sharing!!!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read it and for commenting! Means a lot to me! And I agree with you, it really is a shame how many innocent lives were lost in this tragic event.

Love the story of the Morro Castle! I worked at the NJ Maritime Museum for a little while. There was an entire room dedicated to Morro Castle. The breeches bouy in one of the photos is there, along with some charred life jackets. Inferno at Sea is a great book on the subject. The incident was a huge boon for the asbestos market. So many advertisements with the tag line “ The Morro Castle would still be sailing if they used “Such&Such” Asbestos!

A horrific death for many. I am surprised so many survived. It must have been devastating to watch helplessly from the shores of New Jersey. Fascinating piece of history… thank you.