The Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the 18th century and was a time of reason and enlightenment, of ingenuity and progress, of whistling steam-powered engines and awe-inspiring iron structures. Modernity arrived with the groundbreaking ideas of visionaries who often swung between genius and madness, but in the end changed the world with their inventions. Ideas were bursting all around like fireworks and were not limited to the political and social landscape. They also brought about technological progress on a scale never seen before in the entire history of mankind. Iron bridges, tunnels, factories, trains, ships and other modern inventions quickly spread around the country.

Amongst those visionaries was the renowned engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Brunel was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire on 9 April 1806 to Sir Marc Isambard Brunel and Sophia Kingdom Brunel. His father, also a respected engineer, was originally from Normandy in France and emigrated to England in 1799.

Brunel’s education began in England, where he spent his first 14 years and was later sent to study in the most prestigious schools that Normandy and Paris had to offer. Upon his return to Britain, he quickly gained practical knowledge as an engineer through participation in his father’s projects. In 1831 he began working as chief engineer at the Bristol Docks and designed a number of port facilities.

Later, he moved on to work for the Great Western Railway, where he designed the famous railway connection between London and Bristol. It required the erection of numerous bridges, all of which were personally designed by Brunel. Initially, he relied almost exclusively on wood as building material, although cast iron and welding iron were already in use at the time. Brunel became famous for the innovative bridges he raised along the railway, and he was to design many more all over Britain throughout his career.

But as incredible as his civil engineering projects may be, Brunel’s work as a shipbuilding engineer deserves special attention (at least on this website). When his railway line from London to Bristol finally reached the shore, he made a very fortunate decision – he decided that the journey need not end there. His vision was that once the train reached Bristol, a steamship could take passengers on a Transatlantic voyage all the way to New York. The slogan was as simple as it was bold: “With only one ticket from London to New York”. In 1836, Brunel gathered a group of investors around his vision, and together they founded the Great Western Steamship Company.

The Great Western and the Great Britain

Brunel’s first ship, the Great Western, was still made of wood but it was the first transatlantic vessel designed as a steamship from the onset. The two paddle wheels were each powered by 750 hp coal-fired steam engines. The Great Western was also equipped with four sailing masts for auxiliary propulsion as well as for balancing the ship in heavy seas to ensure that both paddle wheels remained submerged under the water. The ship was finished in 1838 and completed her maiden voyage from Bristol to New York in a new record time of only 15 days. The ship offered a regular service and became a great financial success. This triumph encouraged Brunel to build his second ship, the Great Britain, which he commenced in Bristol in 1839.

The Great Britain was a game changer. Over 95 meters long, it was the largest ship in the world, 30 meters longer than anything previously built. The hull was entirely constructed of iron sheets, held together by rivets.

The real novelty, however, was the propulsion. Despite the lack of support from investors and members of the board, Brunel decided to equip the new ship with a propeller instead of paddle wheels. In a spectacular experiment prior to that, he had had two identical ships, one with paddle wheels and the other with a screw, compete in a kind of tug-of-war on the Thames. The one with a screw won, and Brunel’s test managed to convince the Royal Navy of the benefits of propellers. The Great Britain was thus the first iron propeller ship, heralding a new era of Atlantic travel. The ship initially operated mainly between England and America, but later also served the route between England and Australia.

The Great Britain is now located in a dry dock in the harbor of Bristol and is one of the city’s most visited attractions.

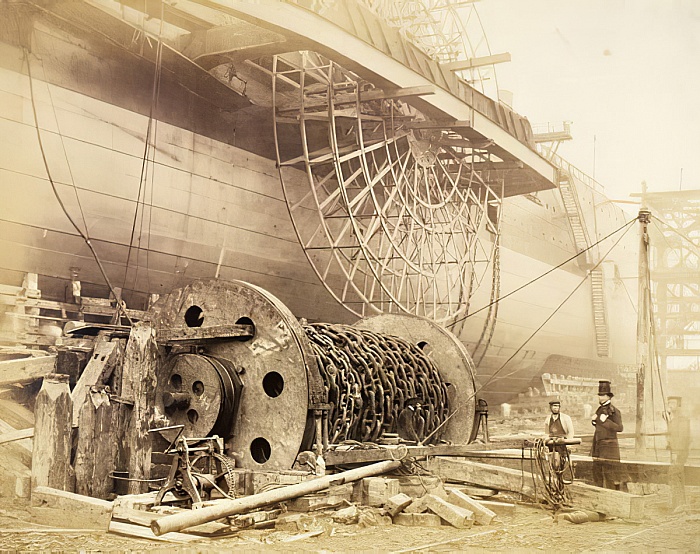

The Great Eastern

Brunel’s work in the shipbuilding world did not stop there. In 1854 he began work on a third ship, the Great Eastern or as he liked to call it, the Leviathan, which was intended to sail the route between England and Australia. This ship was decades ahead of its time in terms of size and technology. At 211 meters, it was more than twice as long as the Great Britain or any other watercraft existing at the time, and it could carry 4,000 passengers. The Great Eastern had a beam of 25.3 m, height of 17.7 m, gross tonnage of 18,915 grt, displacement of 32,000 t, and a draft of 9.1 m when fully loaded.

In addition, the ship had a double hull made of riveted steel plates, with a distance of 0.85 m between the two plating layers. Fearing that coal supplies in Australia would become scarcer and more expensive, the ship was to manage the trip from England to Australia and back without having to reload coal on the way. To achieve this, it was equipped with three different types of propulsion: two 17 m paddle wheels, a large 7.3 m propeller, as well as six sailing masts with sail area of approx. 1,700 m². The paddles and propeller were driven by steam engines with a total output of 8,300 hp, the largest of their time.

Unfortunately, the Great Eastern turned out to be too far ahead of her time. It soon transpired that there was no need for such large passenger capacity yet, and as a result, none of her sailings were profitable. But Brunel was not around to witness her lack of success, as he died shortly after her launch in 1859.

Still, his last creation had its brief moment of fame, when the Great Eastern was sold off and then used for another epic project – the laying of the first transatlantic cable between Europe and America (1865 – 1866). She was the only ship capable of carrying the gigantic cable, even if that required removing the fourth funnel and a part of the boiler to make additional room. The cable alone took five months to load and the Great Eastern laid 4,200 kilometers of it on the ocean floor.

Despite the crew damaging and losing the cable in the course of the project, the first direct telegraph message from Britain to the United States was received successfully in New York in 1866. Later, the Great Eastern was also involved in the laying of telegraph cable between Suez and Bombay.

Final Thoughts

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was no doubt one of the greatest minds of the 19th century, and also one of the most energetic and determined. He broke bones on numerous occasions while at work, received burns from an engine fire during the launch of the Great Western, and once almost drowned while working on the Thames Tunnel. And every time he stood up and harnessed his entire being in his quest for groundbreaking innovation. Despite failing over and over again and struggling with his investors’ disapproval at every step, the short man who liked to be photographed with a giant cylinder to appear taller, changed England like few others before him. He built the longest tunnels of his time, raised breathtaking bridges over deep ravines, and constructed ships that preceded their time by decades. He carried the spirit of the Industrial Revolution by pioneering technological advances and celebrating the inventiveness of the human mind.

See Brunel’s Legacy with Your Own Eyes

If you want to get a feel of the man’s genius, the Brunel museum in Bristol is the place to go. It is only a short boat ride away from the city center and offers something very close to time travel. The dry dock is fully accessible, and one can spend as much time as one likes walking around and looking at the Great Britain from below. Most areas of the ship are open to visitors, including the storage facilities, the passenger and crew cabins, the dining hall, the kitchen and perhaps most impressively, the engine room (!), where a reconstructed working model of a steam engine can be seen up close. For the most enthusiastic Brunel fans, like me, the museum also displays a beautiful, pulse-accelerating, heart-thumping collection of the great man’s notes and technical drawings. In the photos below, you can see some of the areas open to visitors.

The Shipyard