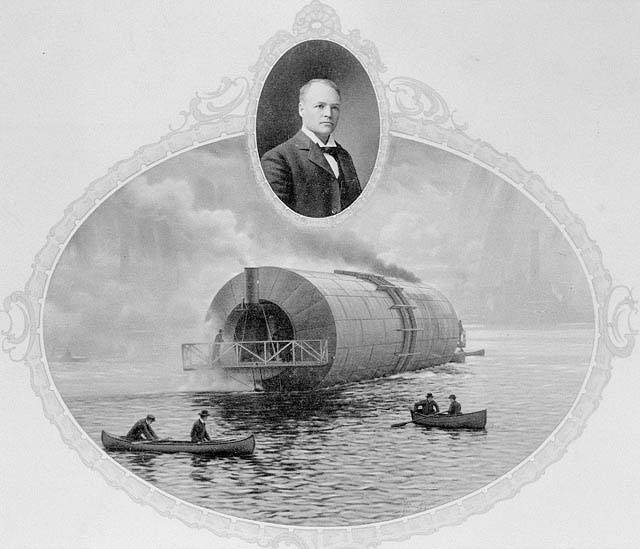

Anyone who has watched a logrolling competition must have wondered how such heavy logs can stay afloat, with people sprinting on top. The same phenomenon must have unlocked the creative impetus of Frederick Augustus Knapp, inventor of the infamous roller boat. In 1897, a crowd of bewildered Toronto residents witnessed the maiden voyage of Knapp’s steam-powered barrel, which promised (or threatened) to change maritime transportation forever. The Canadian inventor’s ambition was to reach 200 miles an hour on the open ocean, while almost insusceptible to the nauseating effect of larger waves. But the maiden voyage on Lake Ontario fell short of these goals, with speed only reaching a couple of miles an hour, before the bizarre apparatus ran aground shortly after departure.

What on Earth Was He Thinking?

At a time of frenzied innovation, when inventors enjoyed the cult-status of modern-day pop stars, the career of a provincial lawyer held little appeal for Frederick Augustus Knapp. He was a man of the world – educated, well-travelled, and ambitious. On his transatlantic voyages, he had often ruminated how to overcome a ship’s speed-limitations, caused by the drag of a hull’s wetted surfaces. The conclusion seemed obvious: minimize contact area and let the vessel roll over the water. Not only would this overcome the major barriers to speed, but it should also increase passenger comfort, as the hull would no longer have to cut through the waves.

Rumormongers said it was vanity feeding the lawyer’s creative aspirations, as Queen Victoria, sovereign of Canada and the largest ever global empire, was known for her travel sickness and reluctance to embark on long-distance voyages. With his determination to cross the Atlantic in twenty-four hours, Knapp could have harbored the dream of bringing the mighty monarch to her Canadian dominion and earning a knighthood.

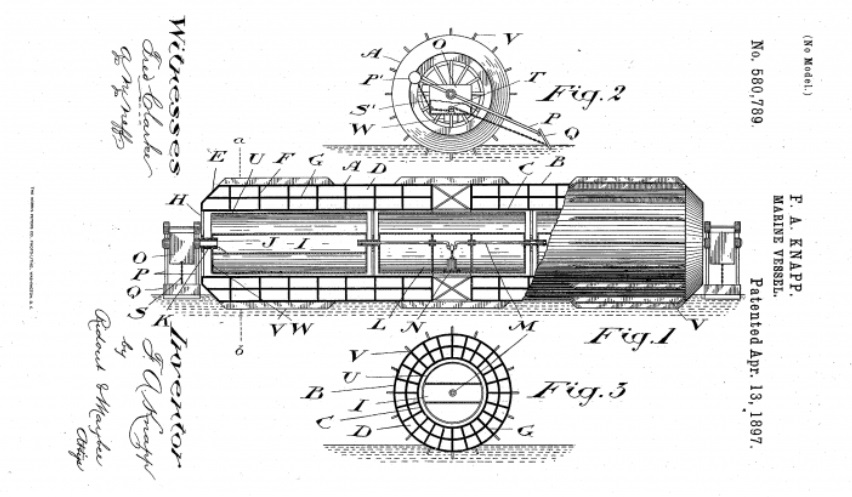

Whatever the motives may have been, Knapp’s efforts at the drawing board produced a design as unorthodox as his ambitions. The boat could be summarized as a giant hollow paddlewheel, with the outer cylinder rotating, while the inner remained stationary to accommodate two engine rooms, a passenger compartment, and some modest cargo space. The stationary section lay suspended in a gimbal mechanism, with the hope that no rolling and pitching from the water underneath would affect passenger comfort or the safety of the steam engines. Propulsion came via several small paddles around the circumference of the hull, while the rudimentary steering system used leeboard-like elements, creating drag on either side to turn the boat.

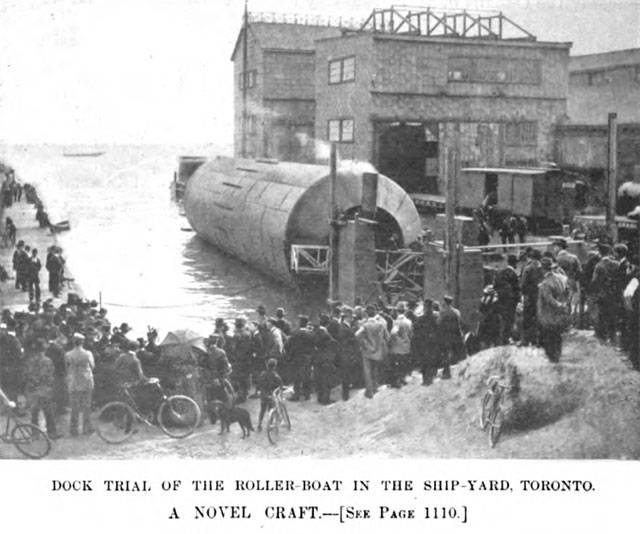

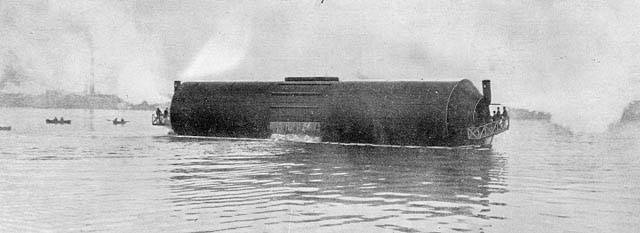

The prototype, built by the Polson Iron Works in Toronto, was 110ft long (33m) and 22 ft (7m) tall – imposing but still a long way from Knapp’s awe-inspiring vision for an 800-foot giant (244m), crossing the oceans with thousands of passengers on board.

Click the images below to visit The Shipyard Shop!

Mother Nature Weighs In

As with many forgotten inventions, the grandest moment for the unnamed vessel was its clash against reality. Creative as he might have been, Knapp neglected several important factors, which would ultimately doom his design to remain little more than a curiosity. In theory, minimal drag could increase speed, but it also left the craft to the mercy of the wind and waves. Instead of rolling over, it would either crash into the waves or roll with them.

On 2 October 1897, a towboat pulled the bizarre contraption out of Polson’s yard and into Toronto Bay, under the gazes of thousands of curious onlookers. There, the vessel made its first baby steps, with speed only reaching a couple of miles an hour. At least the prototype remained afloat, so Knapp called it a success and returned to the dockyard for improvements. The following month, the inventor took the boat out for another spin on the lake, trying a few basic maneuvers to demonstrate the functionality of the steering system. Exuberant as ever, he announced to reporters his intentions to double the size for the next prototype.

Rolling into a Gale

Press and maritime community alike were far from dazzled. Criticism rained from all sides, as engineers, mariners, and journalists sunk their teeth into what they now called Knapp’s Folly. But the inventor’s enthusiasm did not lose steam under the attacks – the following year, he unveiled the improved prototype, this time with conical ends and longer paddles. He even pitched the concept to Washington’s naval circles, expounding its potential as an amphibious troopship, but his pledge to land 30,000 marines on the beaches of Cuba only prompted a few sneers. Knapp’s brief career as an inventor and naval architect was coming to an end.

Rejected and ridiculed, the roller boat embarked on one last journey to Knapp’s hometown Prescott, but forty miles into the voyage, the ill-omened contraption ran out of coal and got stuck in the mud. In the following years, the inventor made a final attempt to salvage his brainchild by converting it into a conventional steamer, but this too failed and the unnamed rusting carcass found its final resting place in Toronto Harbor. Queen Victoria never graced her Canadian subjects with a royal visit.

Was It That Absurd?

The short answer is yes. Much of Knapp’s scientific rationale was flawed and improvised, a fact as obvious to his contemporaries as it is now to us. We know little about his personality and what drove his blind ambition into the mudbanks of Lake Ontario, but history has shown many intrepid inventors falling prey to an overzealous, often vain nature. In the interest of fairness, modern shipbuilding was still in its infancy at the time and was marked by as many follies and fads as any other technology the world had ever seen. So, before dishing out a fresh batch of sarcasm, we should remember that the achievements of each Brunel often step on the failures of a thousand Knapps.

If you loved this post, click here to read about another curious type of ship: the whaleback!

The Shipyard