The late 19th century was an age of vigorous experimentation, with enough talent and money spent on extravagant naval innovations to make our modern shipbuilders blush. And as it often happened in those turbulent days, many inventions barely made a few shaky steps into the world, before sinking into obscurity. One such curiosity was a tiny family of round-shaped monitors, developed in the Russian empire – bold, extravagant, and controversial. Just like the times.

Sailing Around the Rules

The Crimean War (1853 – 1856) ended disastrously for the Russians, with the Treaty of Paris depriving their mighty empire of naval presence in the Black Sea. Alexander II was only allowed a pitiful fleet of six 800-ton corvettes and four 200-ton vessels, which not only neutralized his efforts to challenge Ottoman supremacy, but also created a major defense problem. How does one defend an empire with eight boats?

The navy’s answer was simple enough – by piling onto them as many guns as possible. The only catch was that most compact vessels would sink like a stone under the weight of such armament. But for good or ill, the late 19th century had no shortage of bold visionaries, and Rear-Admiral Andrei Popov was the one to rise to the challenge.

Click the images below to shop nautical hats!

Popov, an ambitious naval shipbuilder, studied the work of Scotsman John Elder on widened beams and calculated that a circular, flat-bottomed ship could carry substantial large-caliber artillery, while maintaining low draft and small displacement. The admiral’s concept still exceeded the tonnage limits nearly three times, but as Prussia crushed France in 1870, the Tsar had a perfect excuse to scrap the treaty and give Popov the green light.

A Paper Tiger

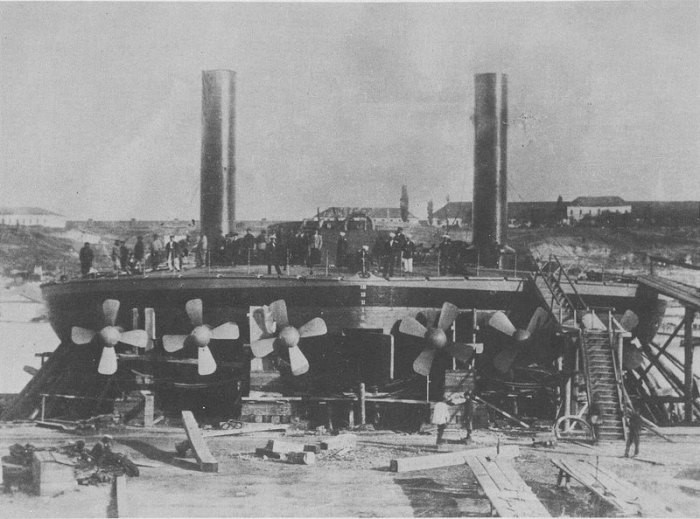

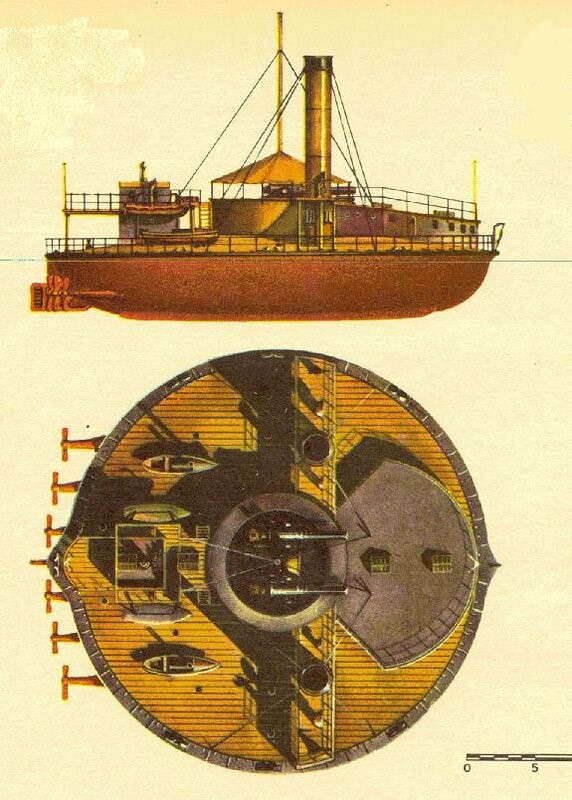

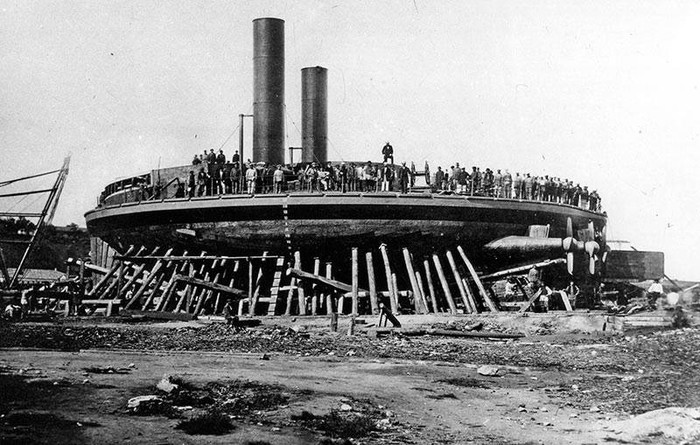

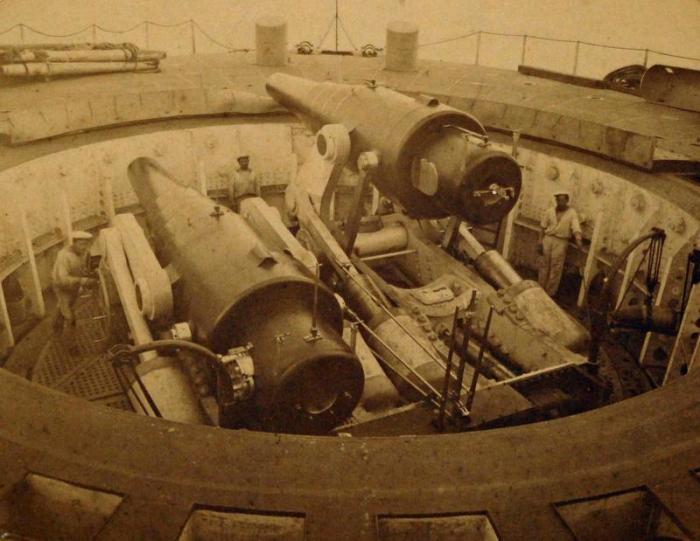

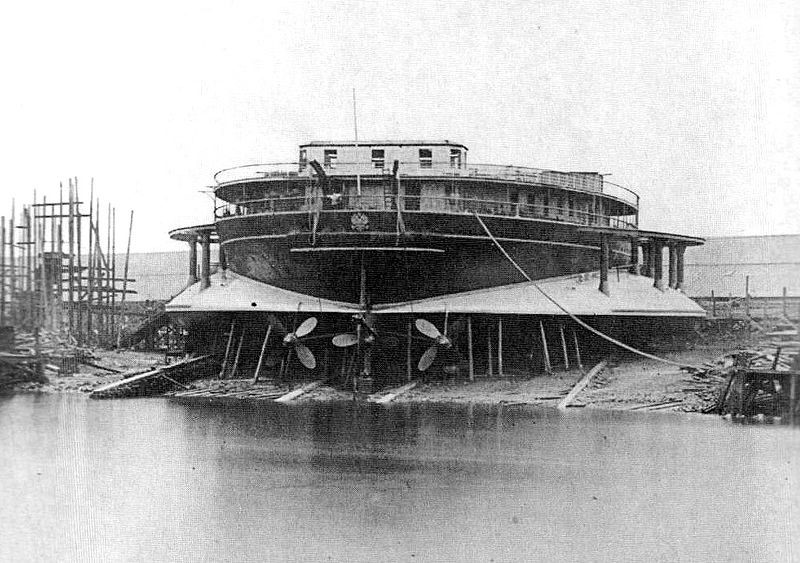

As construction began in Saint Petersburg, the engineers confirmed that the weight of the hull would only be 1/5 of the total displacement, making ample room for the big guns and ultra-heavy armor. The monitor Novgorod came out of the shipyard in 1873 – a 101-feet steel pancake, displacing 2,491 tons with only 12-feet of draft. These 12 feet were even more impressive considering the 9-inch armor of the belt and barbette, as well as the almost fantastic sight of two 11-inch rifled guns, two 4-pound cannons, and two machine guns, all proudly resting on their massive turrets. The main guns were mounted on a turntable, allowing an almost unlimited shooting angle.

On paper, the vessel had achieved important objectives – with her formidable firepower and minimum draft, she could serve as a scarecrow for enemy fleets in the shallow waters around the Crimea. More importantly, Popov now had the Tsar’s ear, and despite some serious technical concerns, Saint Petersburg commissioned a second, larger, and even more expensive pancake – the Kiev, later renamed Vitse-admiral Popov.

With tonnage-restrictions officially lifted by the time, the new ship’s 120-feet length and 3,550 tons of displacement added just 1.6 feet to the draft. What was even more impressive was the increase in armor thickness to 16 inches, as well as the larger 12-inch disappearing guns, complemented by four 4-pounders and two 1.5-inch Hotchkiss revolving canons.

Troubled Water

But as these veritable fortresses sailed out of the Nikolaev dockyard, their shortcomings could no longer remain hidden. To begin with, the ships did not prove agile enough for the open seas. Despite their relative stability and easy roll in calm waters, the popovkas (as they were derisively called after their weaknesses began to show) were a nightmare to stir. In addition, things got so bad in choppy seas that sometimes a wave would cause a propeller to come out of the water. But perhaps the most obvious snag turned out to be speed. Despite sizeable steam engines of 3,360 and 4,480 hp respectively, the round shapes produced four to five times the resistance of a regular hull, meaning that the Novgorod and the Vitse-admiral Popov only reached top speeds of 6.5 and 8.5 knots. And at 2 tons of coal per hour, keeping these top speeds resulted in frightful inefficiency and limited range.

These flaws doomed the popovkas to a brief and inglorious career as deterrent weapons. Deployed in the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878, they neither had the speed to chase the swift Ottoman ironclads, nor the stability to fire the massive canons with any meaningful level of precision. Over the years, the navy kept adding gun after gun to the already cumbersome vessels, hoping to capitalize on the round design’s single advantage. But the two sisters only became older and slower with the years, until wear and tear condemned them to the scrapyard in 1911.

A Sequel Better than the Original

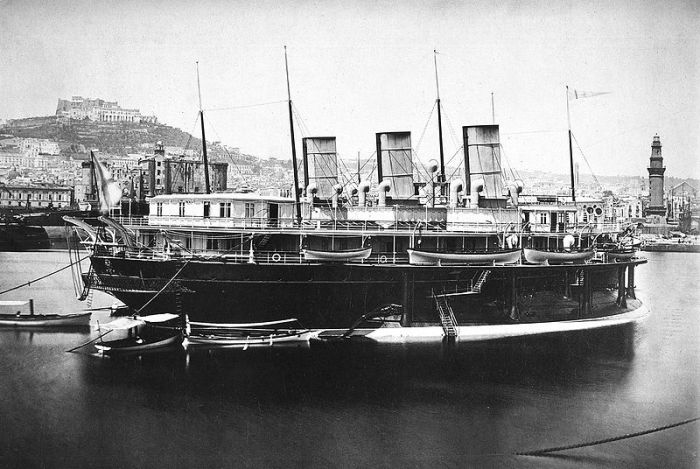

Fortunately for all of us enthusiasts, the story does not end with Popov’s two naval experiments. The cushy sailing experience of a rounded hull may not have been relevant for a warship, but it proved decisive for one particular luxury yacht. In October 1878, the Romanovs’ old imperial yacht Livadia ran aground in Crimea. To fill in the void in the Tsar’s lifestyle, Popov convinced Alexander II to order a new one – large, expensive, extravagant, and…round. The monarch must have been pretty enthusiastic about his new boat, for it took John Elder & Co. in Scotland less than a year to build it.

A regular superstructure mounted on an oval pontoon-hull, the new Livadia took tumblehome architecture to the limit, and although a bit more pedestrian than her extravagant naval predecessors, she far surpassed them in maneuverability and reliability. By then, the Tsar was well-aware of the popovka’s disadvantages, so his condition for acceptance (and payment) of the boat was that the new Livadia could reach 15 knots. The yacht was launched with the expected lavish ceremony, with British newspapers blasting as many superlatives as conspiracy theories. Some admired the 23 steam engines and backup accumulators, while others speculated with a smirk that Britain had been duped into building a battleship prototype for its archenemy.

Click the images below to visit The Shipyard Shop!

Smooth Sailing? Yes and No.

Whatever mix of fact and fiction the media circulated, no one could deny the yacht’s main advantage – she was stable. Despite being likened to a soup plate by some ill-wishers, experts were unanimous that a storm would not even cause a ripple in His Majesty’s soup. What a storm could do, however, was damage the hull. The radial framing created structural weaknesses in the outer sections of the hull, and as the pontoon rose and fell with the waves, the impact could tear the rivets and damage the crossbeams. This is exactly what happened on the yacht’s maiden voyage, resulting in a nasty crack. And since no drydock was wide enough to accommodate the Livadia, what followed was a repair so long and troubled that Alexander II did not live to board his jewel.

Out of Favor

The new emperor, Alexander III, disliked Popov for his extravagant experiments and left the unfortunate yacht to rust for years, until both she and her creator were completely forgotten. The Livadia remained a ghost ship for the next forty years, abandoned and despised, until she was officially struck off the Soviet register in 1926. Thus ended Russia’s expensive but unique adventure with round ships.

Want to read about more strange vessels? Click here!

The Shipyard