Despite years of turmoil, the shipping industry seems more assertive than ever, its long-term ambitions clearly manifested in the current fleet expansion. And though the world’s top 11 carriers have nearly 90 large new vessels in the pipeline, the most bombastic headlines are dedicated to one name: MSC.

This year, the Swiss-Italian group launched four record-breaking ships on the lucrative Pacific route: the 24K TEU MSC Tessa, MSC Irina, MSC Celestino Maresca, and MSC Raya. To equip its new super-fleet for a low-emission future, the Mediterranean Shipping Company has placed an order for 30 Silverstream air-lubrication systems, in addition to innovative scrubbers, energy-saving ducts, small bulbous bows, and large diameter propellers.

But why is this happening now, when the world’s entire logistical chain swings from one extreme to the other, from sudden underutilization to drastic shortages? Moreover, with the political winds blowing towards de-globalization, what motivates such impetus for growth?

Bigger…

Just as the supertanker marked the rise of a global energy market in the post-war boom, giant boxships were spawned by the globalization in mass-production goods after China’s accession to the WTO. As the developed world began offshoring labor-intensive manufacturing to East Asia, cargo volumes between China, USA, and Europe swelled to unprecedented proportions, pushing for rapid expansion and restructuring of the shipping sector. Not only have operators invested heavily in new tonnage (much of it also built in China), but they have been eagerly forming alliances to optimize their operations and gain more control of the business environment. The new Irina, Tessa, Celestino Maresca, and Raya are about to join one of these alliances (called 2M) between the world’s leading container carriers, MSC and Maersk.

… And Cleaner?

MSC (like most other majors) has made a bold investment to enter a transition phase towards a future without fossil fuels. The most notable feature of the new giant carriers is the air-lubrication system. Developed by Silverstream, it aims to mitigate the main energy-consuming factor: friction between the hull and the water. By injecting tiny bubbles along the entire hull bottom, the system forms a sheath of air, reducing frictional resistance and, thus, fuel consumption.

Further improvements in efficiency come from the vessels’ energy-saving ducts, mounted in front of large-diameter propellers. These ducts are simple but clever fins, which help straighten and accelerate the hull wake before reaching the propeller, amplifying thrust. And speaking of propellers, the shafts of the new vessels will be further enhanced with generators for added power.

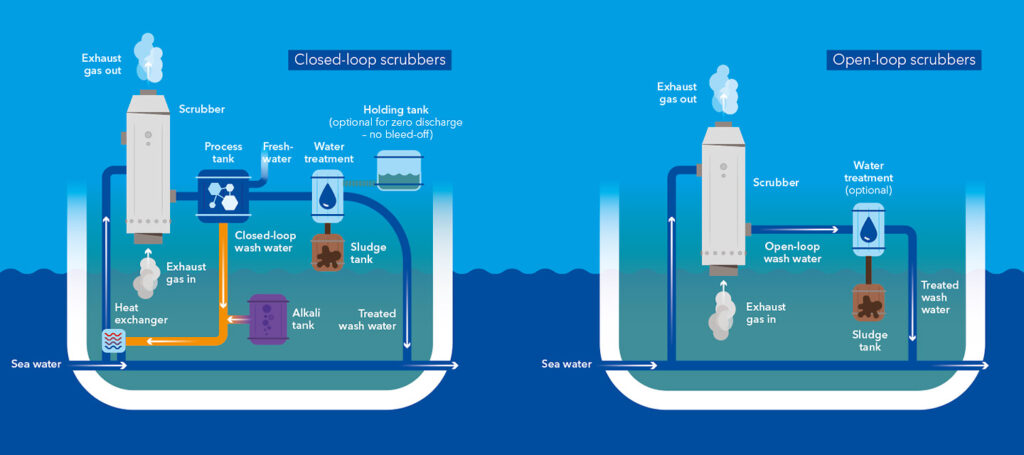

Finally, all mega-carriers in the series have advanced scrubber systems, aiming to conform to the IMO 2020 criteria for mitigating global marine pollution. The new standards stipulate that sulfur content in marine diesel be reduced from 3.5% to 0.5%. This leaves operators with two choices – burn expensive clean fuel or install systems to remove the harmful sulfur oxide from the exhaust fumes. So far, scrubbers are winning. A (wet) scrubber system sprays an alkaline solution of sodium hydroxide or calcium carbonate into the exhaust to neutralize the acidic sulfur oxides, forming a sludge, which is then collected and filtered out.

A Transitional Fleet

In addition to the eight super carriers, MSC is rumored to have placed orders for six dual-fuel vessels, as well as ten LNG-powered boxships with the latest ammonia-ready design. The environmentally sustainable fleet may not comprise a massive percentage of the company’s total acquisition of 134 new and 271second-hand ships but, in the context of the recent global turbulence, is nevertheless an impressive and slightly puzzling investment.

Poor Timing or Strategic Competence?

Considering the years of COVID-induced chaos in global logistical networks, further exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some analysts criticize the current fleet expansion as rash and risky. After all, lockdowns may have spiked orders of physical goods from China, but as life returned to normal, consumers resumed their interest in services, causing a sharp drop in shipping demand. Add the sanctions against Russia with the resulting petroleum-crisis, and the growing number of LNG-fueled vessels makes even less sense. Finally, there is the decoupling between the West and China, with the USA embracing friendlier and less powerful nations like Mexico, India, and Indonesia. This process is expected to reduce the volume and regularity of Pacific trade, which is crucial for the profitability of mega cargo ships like MSC’s new giants.

So, are shipping companies really making a huge gamble?

Not necessarily. While each of the above arguments makes sense in a broad political context, business factors will continue to shape reality on the ground. True, shipping rates have dropped from their recent record-high, but the last three years have also offered good opportunities for shipowners to retire obsolete equipment at favorable terms. Material shortages have led to high metal prices, with shipbreaking yards paying good money for old vessels, which were bound to be scrapped anyway. In addition, the regulatory environment is making firm steps toward a more environmentally responsible future, so investments in cleaner fleets are likely to pay off in the long term.

On another front, while the rift between the USA and China is affecting global logistical chains, this process is not as uniform and aggressive as presented by the media. Despite the political push, China’s manufacturing sector is mature and optimized, offering smooth operations and serious economic benefits. Western companies, having invested billions over the last forty years, are unlikely to withdraw as quickly as Washington would like it. Apple’s troubled attempts to diversify its manufacturing base to India is just one of many examples. In this sense, MSC and the other shipping majors have made an educated bet on the future of large-scale Pacific trade.

Nevertheless, the petroleum crisis resulting from the Ukraine war is a fact. While regular bunker fuel can be sourced from multiple locations across the globe, cutting off Russia from the world economy has eliminated the most reliable exporter of natural gas. With the war turning into a geopolitical swamp, an LNG-fueled transition to a low-emissions economy is likely to remain unstable.

Wonder how these giant ships stay upright? Find out here!

The Shipyard