Back in September 2019, Saint Simons Island in Georgia had one of those idyllic promenades many wished they could retire to – sandy beaches, rows of palm trees, serene sunsets, a colossal keeled-over hull, rising like the cadaver of an ironclad whale… Wait, what? Yes, the MV Golden Ray. The story of its capsizing reads as if Murphy forged his proverbial Law precisely for this unfortunate car carrier, a reminder how a seemingly small human error can trigger a catastrophic chain.

The When, Where, and How

In the early hours of 8 September 2019, the RoRo vehicle-carrier MV Golden Ray headed out of Colonel’s Island Terminal at the Port of Brunswick. It was an ordinary maneuver in calm weather conditions, the experienced pilot minutes away from completing his routine task and disembarking the vessel. With all systems on board well into the green zone, the Golden Ray parted with her tugboat and went for a final starboard turn out of port and into the Atlantic. Then, out of nowhere, the ship made a heavy list to port. Crewmembers gasped.

“What’s the GM on this thing?” exclaimed the pilot.

The answer came from the ship herself, as she heeled further down. Both pilot and master barked orders to the helmsman amidst the din of numerous alarms, but when the equipment began to slide and crash to the floor, everyone in the bridge knew what was coming. At 1.38 in the morning, the Golden Ray ran aground with a 60° list to port. Water rushed through the open pilot door, flooding the area around the engine room. Within minutes, the propulsion systems and all electric generators were dead, leaving everyone on board in complete darkness.

The Rescue

The pilot wasted no time, calling out to a nearby vessel for help. Anxious to prevent the Golden Ray from sinking in the deeper waters, he also contacted a towboat operator, requesting the dispatch of several tugs. Finally, he signaled the local Coast Guard for assistance. The reaction was immediate – two pilot boats and two tugs rushed to the site, followed by the local Coast Guard’s 45-foot response vessel and MH-65 helicopter. After a brief consultation, the tugboats pushed the Golden Ray into the relative safety of the nearest riverbank, securing enough stability for the rescue teams to begin their intricate operation.

Within the first hour, 11 crew climbed down a hose from the bridge to the response boat, among them the master and the pilot. They brought bad news – among the 13 crewmembers left on the ship, three engineers and one cadet were trapped in the engine room. And even though seven others were rescued in the following hour (two hoisted by helicopter from the side of the hull), for the four stranded in the engine room, things took a turn for the worse.

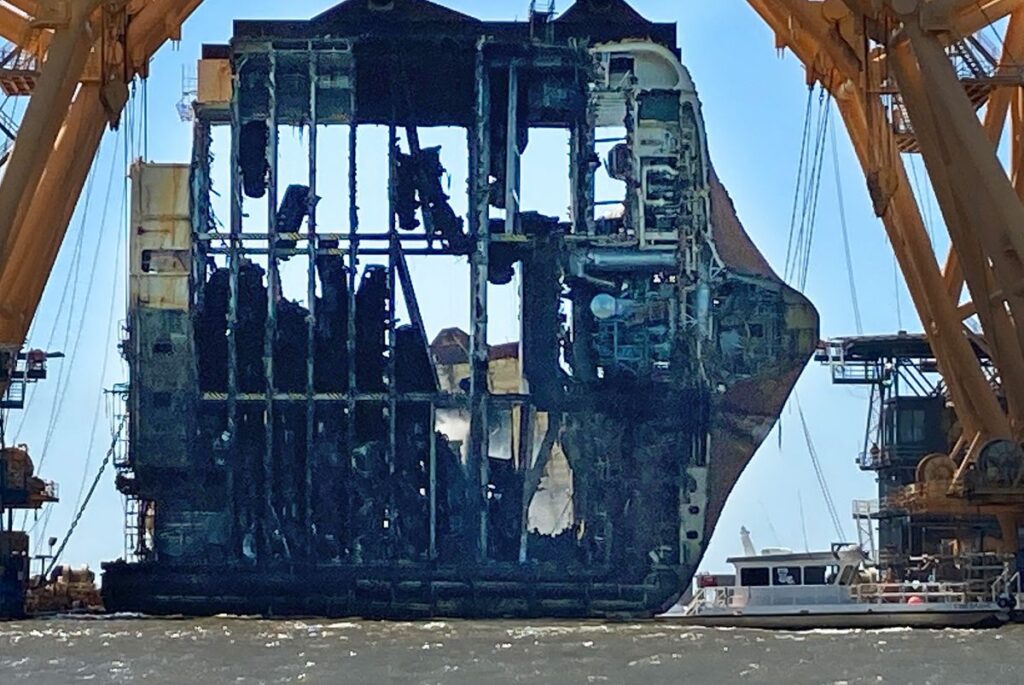

At 4.30am, flames and clouds of smoke belched out from the vehicle compartments. With the cargo holds full of combustible materials, the heat got so intense that rescuers decided to suspend attempts to reach into the vessel for 24 hours. The only signs of life from the trapped engineers were the occasional taps reaching out through the groan of steel plates.

In the meantime, another threat lurked beneath the water surface – the soft, silty bottom of the channel gave in under the weight of the hull, and the Golden Ray heeled to a full 90° angle. Dozens of cars with partially filled tanks crashed together into a corner, threatening with more fires. After consultations with local authorities and salvage experts, the Coast Guard issued a somber verdict: due to explosion hazards, access could only be secured by cold cutting. The nearest equipment was 14 hours away.

To the ones trapped inside, this was a death sentence. The engine room was already turning into a furnace, with temperature readings as high as 155°F (68°C) and toxic fumes spreading throughout the ship. Fortunately, sound minds took the upper hand in the rescue team outside, and the cold-cutting plan was quickly scrapped in favor of a simpler and smarter solution – to drill connected holes and form a square opening into the hull. Two frantic hours later, at 3.00pm, three of the men were pulled out of the engine room. At 5.51, after rescuers managed to break into the engine control room, the last engineer emerged from the wreck, alive and well.

A Few Days Earlier…

Nine days before the accident, the Golden Ray left Freeport, Texas, taking a course for Brunswick. Soon after, a message arrived from the charterer Hyundai Glovis that Hurricane Dorian was making its way up the coast of Florida. The master commanded the chief officer to top up the ballast tanks with 1,500 tons of water (a standard procedure to increase stability in rough seas) and steered the ship to a sheltered location to wait out the storm.

With Dorian out of the way, another message from the charterer ordered an unexpected stopover at Jacksonville, where draft restrictions required releasing all that extra ballast water. Later, upon arrival at Brunswick, the pilot saw nothing unusual in the ship’s steering. Loading and unloading were also uneventful, and so were the soundings the quartermaster did for all tanks under the chief officer’s supervision. The Golden Ray seemed in perfect shape and ready to depart.

“What’s the GM on this thing?”

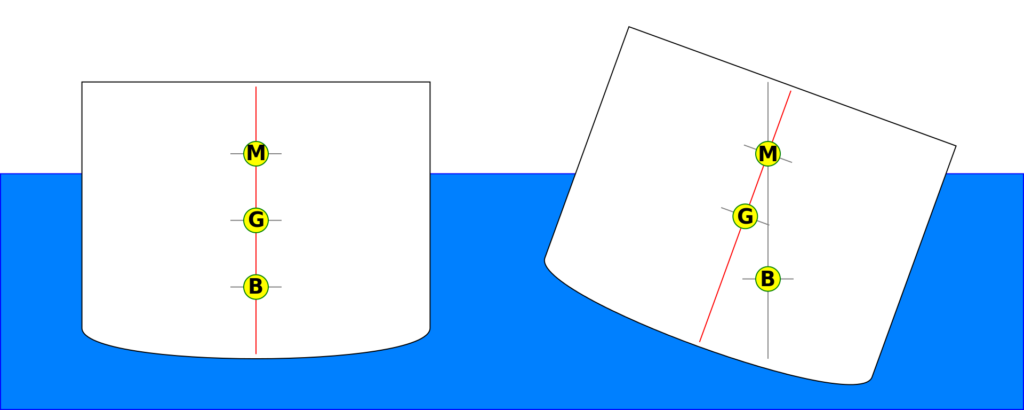

The pilot’s startled comment at the time of the accident summed up the lengthy forensic investigations that followed. The GM (or metacentric height) of a ship is the distance between her center of gravity and the metacenter. The lower the GM, the smaller the righting force when the vessel heels over. In short, a ship with low GM is more likely to capsize during a maneuver.

Before leaving Brunswick, Golden Ray’s chief officer calculated the GM at 2.5 meters (around 8 feet), which allowed enough margin of error and was duly accepted by both the ship’s LOADCOM computer and the master. However, simulations of the Coast Guard’s Marine Safety Center (MSC), established that the actual GM was closer to 1.8 meters – an unacceptable value that, if known at the time, would have prevented the ship’s departure. Stability was further compromised by the pilot door, wide open for the pilot’s departure, which let in large quantities of water that further compromised stability. What is more curious, however, is a statement in the 2019 Marine Accident Report that “with 1,492 MT additional ballast, the vessel would have been in compliance with the current international stability standards”.

If the number rings a bell, it is no coincidence – this is the amount of ballast water the chief officer topped up in preparation for Hurricane Dorian, and the same quantity he discharged prior to entering the Port of Jacksonville. But how does a 1,500-ton error happen on a modern 71,000-ton vessel, operated by a major international company? Cargo loading had gone as planned, IMACS readings had been cross-checked as required, tanks had been sounded, stability calculations had been verified, and all the data had been passed through the LOADCOM computer. Except for one little detail.

Further probing identified that, instead of letting the IMACS system feed readings automatically into the LOADCOM, the chief officer had entered everything by hand. The reason – he had not been trained by the operator to use the full features of the LOADCOM and often resorted to manual input. And even though the LOADCOM sustained irreversible damage before being retrieved by the salvage operation, an accidental omission of this ballast discharge is not an improbable cause of Golden Ray’s capsizing.

The Aftermath: An Expensive Mistake

The timely intervention of rescue brigades prevented casualties, limiting the seriously injured to two and extracting the remaining 22 unscathed. Financial damages, however, were stupendous – in addition to a complete write-off of $62.5 million for the Golden Ray and $142 million for her cargo, the extensive salvage operation topped $840 million, exceeding by far maritime disasters such as Exxon Valdez.

And while the operator has implemented advanced training and communication procedures since the accident, experts cannot help but ask the question – was this an isolated case of human error and corporate oversight, or a habitual practice in an industry so focused on cost reductions that it would compromise on safety?

The Shipyard

Read more about ship stability here!

Thanks for the insight and sign off statement. Getting into aviation we too study about how there is an oversight and increased appetite in risk allowance in the name of reducing costs and increasing margins.

They’re called accidents for a reason, but prevention through isolation and omission can go a long way.

I appreciate the work you put into mainting this blog and the insta page. Keep up the good work!

Thank you for your encouraging comment! I really appreciate it.