Streamlined muscular design, chrome on the outside, leather on the inside, monstrous power under the hood… No, this is not Elvis Presley’s pink Cadillac. We are talking about the NS Savannah – the world’s first nuclear merchant ship and, without doubt, one of the prettiest. This is a story of great shipbuilding, bad timing, and a world in which beauty is always tragic.

A President’s Expensive Toy

The world after Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a scary place, with billions across the globe trembling at the prospect of total annihilation. Political and military elites, however, could not turn their backs on the shocking effectiveness of atomic warfare and waited for the right moment to present their case to the skeptical public. The opportunity came in 1953, when Stalin’s death sparked some hope in the West that the looming Cold War (or worse, a hot one) could be thwarted in favor of international cooperation.

Taking advantage of the nation’s reluctance to another major conflict, President Dwight D. Eisenhower publicly denounced arms spending as a theft from the people and a waste of precious resources. Thus began the White House’s calculated propaganda campaign for controlled nuclear militarization as a byproduct of a peaceful atomic future. Branded as “Atoms for Peace” after Ike’s famous speech, the strategy aimed to showcase civilian applications of enriched uranium and gain popular support for the development of nuclear technologies.

The most prominent global ambassador of Eisenhower’s initiative was a groundbreaking merchant vessel, propelled by a nuclear reactor. Completed in December 1961, NS Savannah was America’s response to the 1957 Soviet ice-breaker Lenin, which was the first nuclear civilian ship. With a hefty price tag of almost $50 million, the Savannah sported an avantgarde Atomic Age exterior and meticulous luxury interiors, down to even the cargo-handling equipment.

Why the eccentric lavishness – this beauty was meant to be seen. From her maiden voyage in 1962 to her deactivation nine years later, the Savannah toured 77 ports, attracting 1.4 million visitors. And although she ultimately failed to convince civilians in the benefits of nuclear transportation, the NS Savannah still stands proud (and defueled) in all her beauty at the Port of Baltimore.

Atoms for Luxury

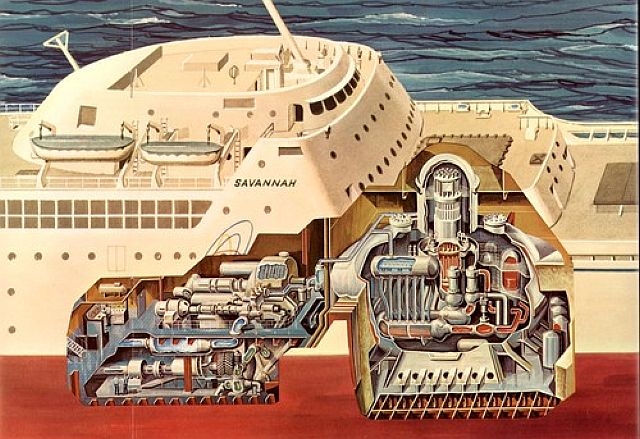

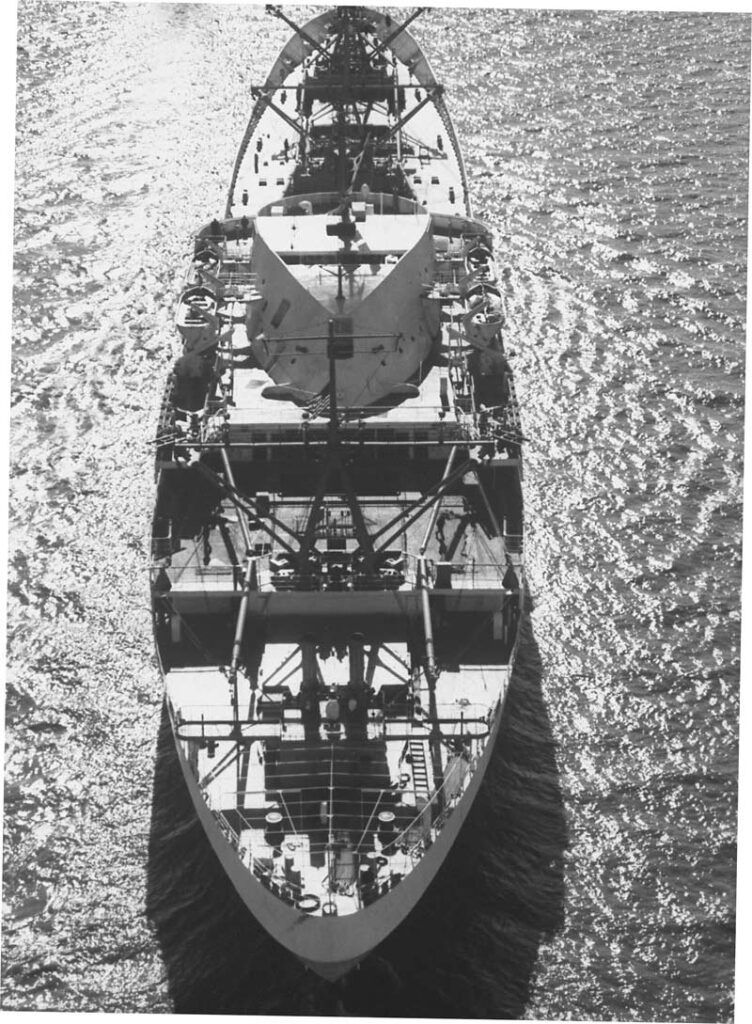

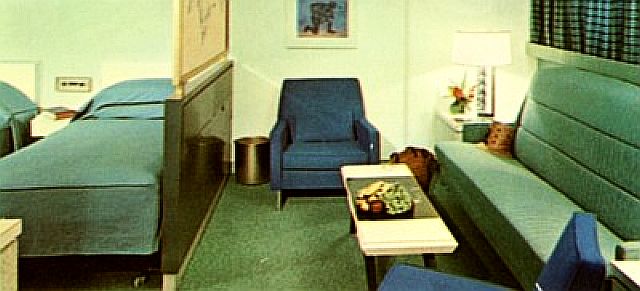

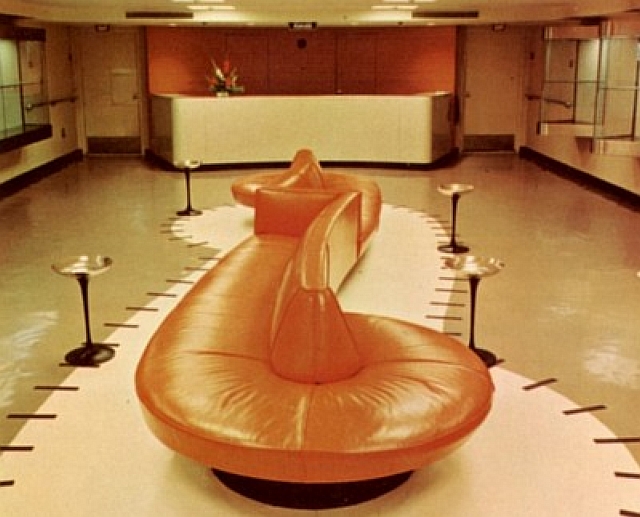

At just below 600 feet in length, the visually striking prototype combines 8,500 short tons of cargo capacity with 30 staterooms, furnished with enough luxury to impress a billionaire or a monarch. The seven cargo holds are distributed around the ship in a somewhat odd manner, to allow the reactor a central position with top access for refueling. However, the designers at George G. Sharp managed to turn this shortcoming into a visual advantage, placing the superstructure to the aft and giving Savannah the muscular appearance of a superyacht. Four holds are fore of the bridge, and the fifth one is directly beneath the swimming pool, requiring special side ports for loading and unloading.

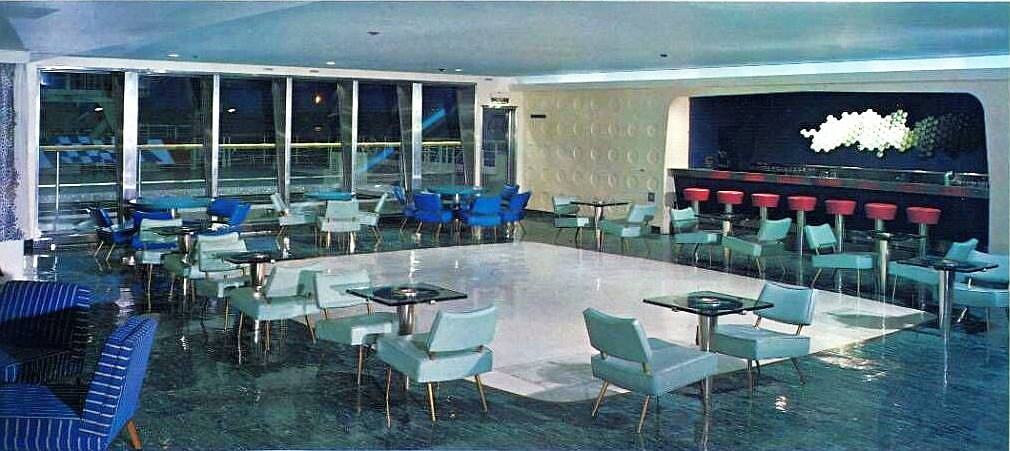

This distribution left precious little space for passengers (three full decks), but the level of luxury on board implied that this vessel was not for the mass consumer. Inside, the Savannah looked like the set of a James Bond film – glass outboard walkways, illuminated tables at the bar, a kitchen with one of the first microwave ovens, as well as numerous science-inspired modern artworks. All this grandeur surely impressed the public, but with less than 850 passengers carried in the ship’s entire career, it was clear that the nuclear stigma kept people at bay.

Space Age on the Seven Seas

To ease popular fears of its 5,248 enriched-uranium pellets, the 74MW Babcock & Wilcox reactor was conceived as a masterpiece of safety and reliability. Shaped as a tall and slim cylinder, it operated inside a steel containment vessel with wall thickness reaching 4 inches – enough to withstand the enormous pressure from a ruptured coolant pipe, one of the main hazards of nuclear power.

In addition, the containment vessel’s floor had designated manholes to let in water and equalize the pressure in case of sinking, preventing the walls from caving in. As for collision protection, the sides of the containment vessel had a 1-inch steel armor, padded with 3 inches of soft redwood. Finally, all this high tech was backed up by diesel generators, capable of powering the ship’s propulsion, as well as the reactor coolant pumps.

Failed but Not a Failure

From a technical standpoint, the Savanah was a relative success, with one minor instrument malfunction during her maiden voyage, which shut down the reactor. Despite the huge negative publicity that the incident received, it demonstrated the system’s responsiveness to glitches in the equipment. The rest of her career was smooth sailing, with 450,000 accident-free miles, stopping at multiple locations in 26 countries.

What was less impressive was the quantity of radioactive waste, especially in the beginning. Her modest size limited the waste storage capacity to 10,000 gallons, so in her first year of operation, the Savannah released 115,000 gallons of contaminated water at sea. Later improvements dealt with valve leaks, reducing these emissions to the ship’s onboard capacity. In addition, the Todd Shipyard in Texas supplied the Savannah with its own lead-lined servicing barge, NSV Atomic Servant, which could help discharge waste and provide spare parts at any location in the world.

Commentators also criticized the Savannah for being uneconomical and impractical with her bloated crew, expensive operation, and impossible insurance status. After all, the post-war economic boom of the 50s and 60s ran on cheap fossil fuels, and by the time the Arab oil embargo shocked the world in 1973, the Savannah experiment was history. Had she survived another year to see the surge in oil prices, her economics would have been more convincing.

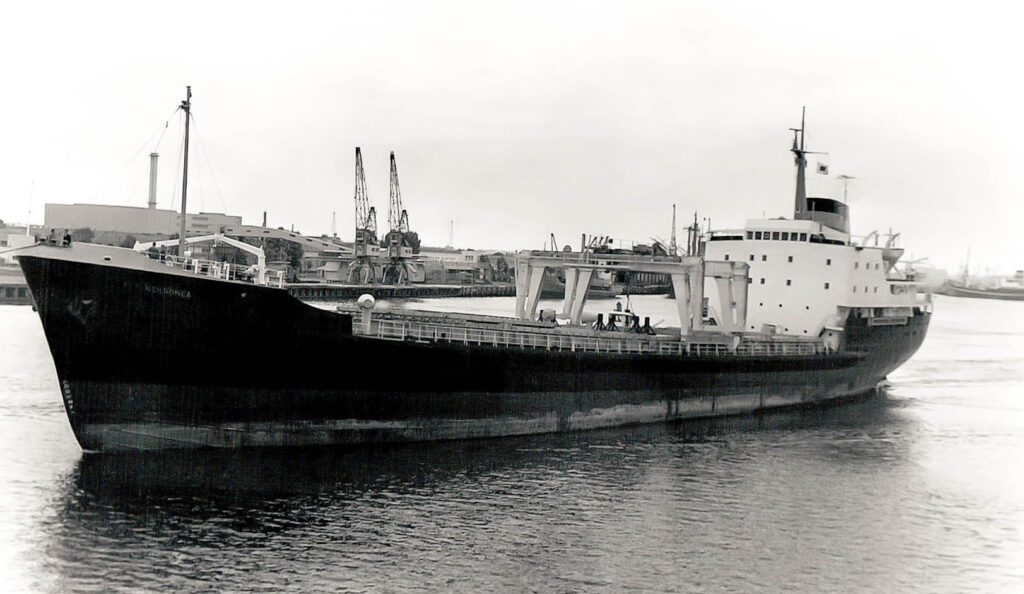

But what really doomed the prototype were not operating costs or radioactive emissions. Two years after Savannah’s maiden voyage, Australian Steamships launched the MV Kooringa – the first fully cellular purpose-built container ship. From that day on, there was no turning back. A quick look around any major port in the world makes explanations redundant – the NS Savannah was a breakbulk freighter in a world of containers. As impressive as she was, she simply became irrelevant.

And finally, we have politics. The Savannah took six years to complete, and those who had conceived the idea of a peaceful nuclear future in 1955, were already losing faith in it by 1961. The doctrine of nuclear deterrence was taking shape fast, with both the US and the Soviet Union jumping boldly into a chain of proxy wars – an excruciating model that defines the multipolar world to the present day. All this considered, one could say that the gorgeous NS Savannah did not fail, it was failed.

The Shipyard

Keep scrolling for more photos of the Savannah below.

P.S. If you found this article interesting, you might enjoy reading about nuclear-powered icebreaker Yamal here!

It should be noted that the Savannah only carried passengers for two years but during that time the staterooms were 100% booked. No “nuclear stigma” kept them away. Passenger service was discontinued after the demonstration phase to cut costs of the extra staffing required. There are several other minor inaccuracies such as her being the USA’s answer to the Lenin, Savannah’s construction was approved in 1955 well before Lenin’s launch, in 1957

Thank you very much for the information, I appreciate the feedback! I will make some edits to the article.