The atomic bomb defined the latter half of the 20th century and continues to shape the global geopolitical framework to the present day. The prospect of total annihilation on both sides of the Iron Curtain turned kinetic war into a complex strategy of deterrence, with each camp doing their utmost to discourage the other from making a move – a global peacock dance with a plumage of ballistic missiles. And if the A-bomb was not scary enough on its own, the rise of nuclear technologies spawned a new breed of submarines that could not only remain submerged for months but also carried enough firepower to torch an entire continent.

The thought of a nuclear reactor crossing the oceans, loaded with weapons of mass destruction, made civilians across the globe bristle with terror. The navy did not even have to launch any of its deadly toys – a mere accident with this novel technology could alone spell the end of all humanity. And while mishaps did happen, they often remained shrouded in secrecy, both to avoid public condemnation and conceal strategic weaknesses. In fact, decades after the end of the Cold War, both press and academia still often rely on leaks and educated guesswork.

Just reading about these made my hair stand on end, and with Halloween approaching fast, I decided to share this feeling with you. Let us be thankful that we are still here to enjoy a good story.

Soviet K-108 vs. USS Tautog

To vastly oversimplify things, nuclear submarine tactics are a cat-and-mouse game, in which an attack submarine (or hunter-killers) of one country shadows a ballistic-missile submarine (SSBN) of another. If command is given to deploy the nuclear missiles, a hunter-killer’s task is to destroy the SSBN before the latter can carry out orders. Attack submarines like to approach from behind, as the noise from the SSBN’s propellers often creates a blind spot for the sonar.

This was exactly what the USS Tautog was doing on 20 June 1970, when it literally bumped into a Soviet 675-class cruise-missile carrier near the USSR’s Pacific base in Petropavlovsk. Russian captains often made abrupt maneuvers to clear the blind spots in the sonar, and the American boat failed to detect one of them. Seconds later, the K-108 landed on top of the Tautog, crushing its superstructure. Both submarines escaped to base without casualties but with significant damage, a sizeable piece of the K-108’s propeller even getting lodged in the Tautog’s hull. The incident remained classified for twenty years.

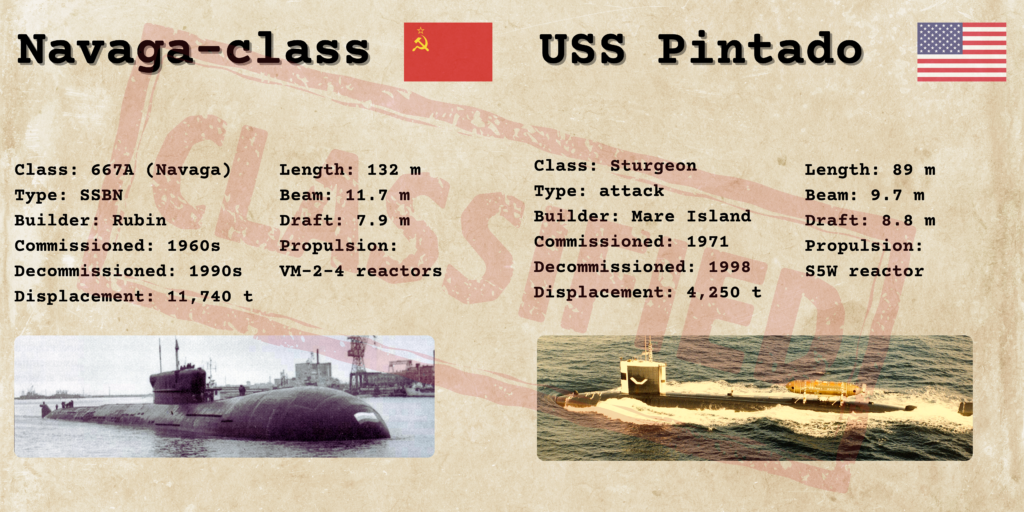

USS Pintado vs. Soviet Navaga-class

By the mid-1970s, the oceans were brimming with underwater espionage, leading to frequent incidents that forced both sides into awkward silence. In May 1974, the USS Pintado was lurking near the Petropavlovsk naval base in Kamchatka, when it rammed almost head-on into a Soviet Navaga-class SSBN, which remains unidentified to the present day. How and why both U-boats failed to detect each other is still a mystery – we only know that the USS Tautog suffered moderate damage, while rumors about the Russian side range from a few scratches to significant loss of life. Only scraps of information leaked to the media in the following decades, too vague and fragmented to make waves.

Soviet K-211 vs. HMS Sceptre

A near-disastrous scenario unfolded in 1981 between a Russian ballistic carrier and a British hunter-killer in the Barents Sea of the Arctic Ocean. The incident would have been worthy of a Hollywood screenplay, had it not been kept under lock and key by both sides for decades.

Following the well-established routine, the K-211’s captain issued a command to halt the boat and run the sonar to clear the blind spots at the stern. The equipment returned no indication of threats in the vicinity. A few minutes later, though, the entire vessel tremored with a series of impacts that made everyone on board skip a beat. After a few horror-filled seconds, the K-211 surfaced, and the crew inspected the damage, concluding they had been hit by a US Sturgeon-class submarine.

Don’t forget to visit The Shipyard Shop!

Shortly after, however, the British press reported that the Royal Navy’s Sceptre had suffered a collision with an iceberg and had returned to base with extensive damage. The iceberg-theory fooled no one, and the smell of intrigue filled the air between Devonport and Petropavlovsk.

The story of the Sceptre was publicized much later, confirming it was indeed the British vessel that had crashed into the 544-foot Soviet monster of mass destruction. Records indicate that even though the Sceptre was quick to bolt from the crime scene, the damage was so extensive it very nearly sank the boat. In a split second, the captain activated the manual override to avoid the automatic shutdown of the reactor and kept the boat in operation. When they finally surfaced, the crew uncovered the chilling extent of the damage – a frightful gash stopped a few inches short of the forward escape hatch, which, once breached, would have plunged the Sceptre to the bottom of the sea.

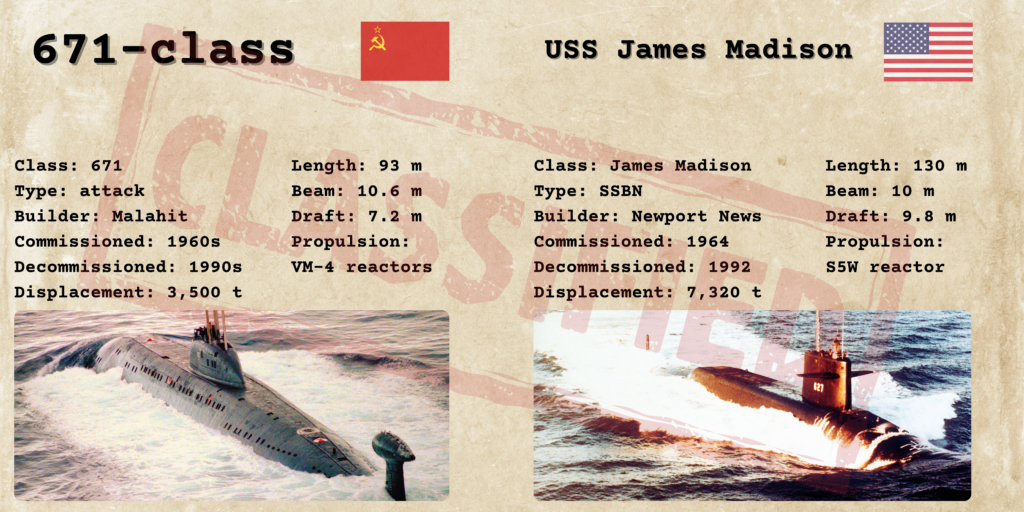

Soviet 671-class vs. USS James Madison

After 43 years of secrecy, many in 2017 shuddered that this incident in British territorial waters could have sparked a nuclear war. Russian media downplayed the more bombastic claims in the West, but no one could ignore the fact that both sides must have had a good reason to remain tight-lipped for decades.

On 3 November 1974, an attack submarine of the Soviet 671-class nearly sank NATO’s ballistic flagship a few miles off the coast of Scotland, while the US vessel was armed to the teeth with 16 cutting-edge Poseidon missiles. What set this incident apart was the daring maneuver of the Soviet captain, penetrating deep into British territorial waters near Holy Loch – a major US submarine base from 1961 to 1992. Following the well-established tactic, the Victor-class submarine was supposed to wait for the James Madison in international waters and follow it as the latter submerged in the North Atlantic. But the US boat was already under water at the time of the collision – an unusual practice in the narrow waterway of Holy Loch, which may have caught the Soviet crew by surprise. The nasty collision must have shocked both crews, as the two vessels surfaced for a frenzied inspection of the damage, before the Russians submerged again and made a hasty getaway.

The reasons for the Russian captain’s bold and risky move may never be revealed, nor shall we ever know if this was an isolated incident or a custom, but we could guess why NATO kept silent all these years. Even though Holy Loch was a US base, guarding the coastline was the responsibility of the Royal Navy, and neither ally was too eager for the nuclear blunder to reach the public. Despite Holy Loch’s perfect location for a nuclear strike on the USSR, the Scottish population vehemently opposed the base for the contamination risks it presented, and this near miss would have added oil to the fire. As for the USSR, the last thing the Kremlin needed was having to explain a brazen violation of British sovereign territory to an already skeptical audience.

Want to read more about nuclear power? Click here to read about icebreaker Yamal!

The Shipyard

Great post, brought back “fond” memories of my time at sea in the 1980s. Only comment would be gilding the lily — putting the NATO codewords for the Soviet boats “Echo II”, “Charlie” and “Delta” respectively for the first three entries would be helpful, as you have done with “Victor” in the last.

Thank you for your comment! Great suggestion, I will add them.