If you have ever been to a modern-art gallery, you must have heard the likes of:

‘Hmm…what am I looking at?’

‘What in the world is this?’

‘Which square is her face again?’

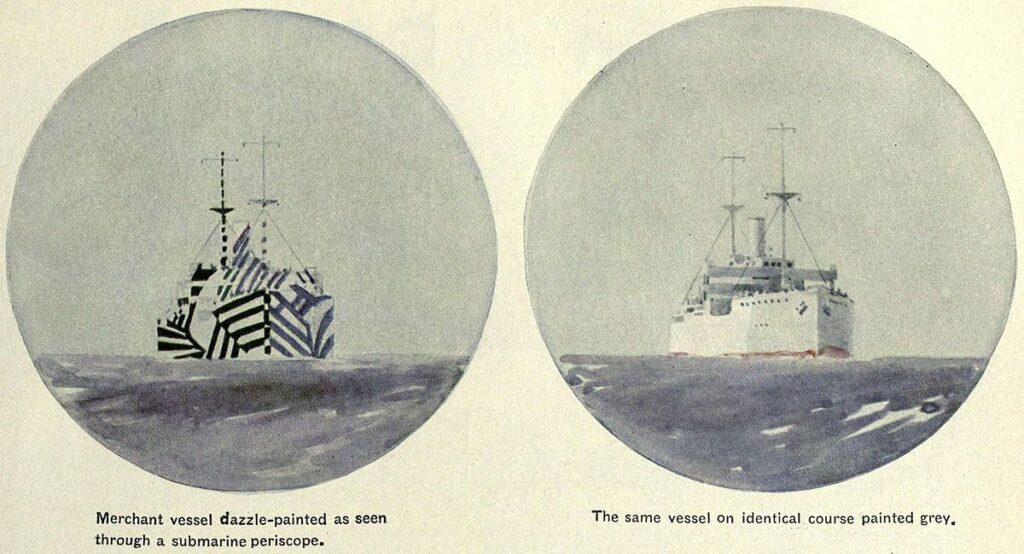

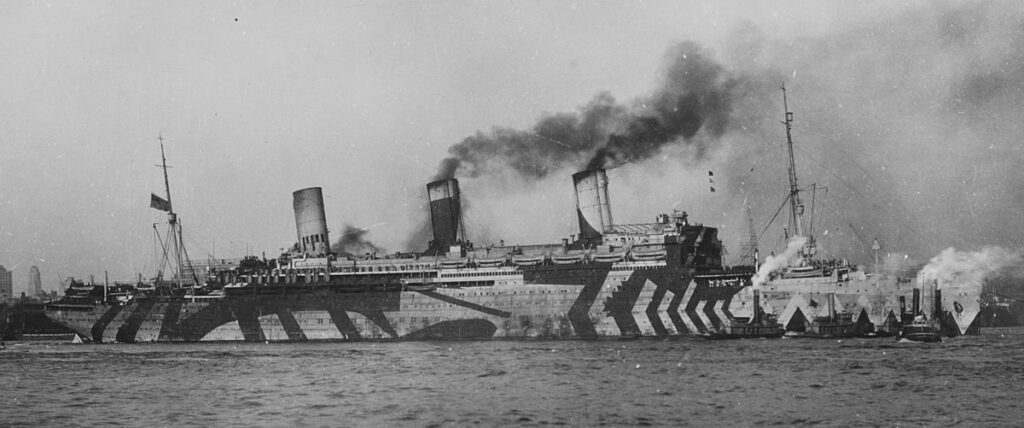

Now imagine the same bewildered conversations taking place inside a German U-boat, in the summer of 1918. The gunner has had a few brief moments to peek through the periscope and to make a quick appraisal of an enemy ship’s type, speed, and direction. With a brain trained to work like a computer, he knows what he is doing, having sunk many British vessels since the German Empire began unrestricted submarine warfare three years earlier. But what he sees through the periscope today looks more like a Picasso painting than a troopship – giant stripes of black and white, random geometrical patterns, inverted perspective. The German gunner holds his breath, makes a guesstimate of the thing’s trajectory, and fires a torpedo. He misses. Thus begins the story of a crazy and brilliant invention: dazzle camouflage.

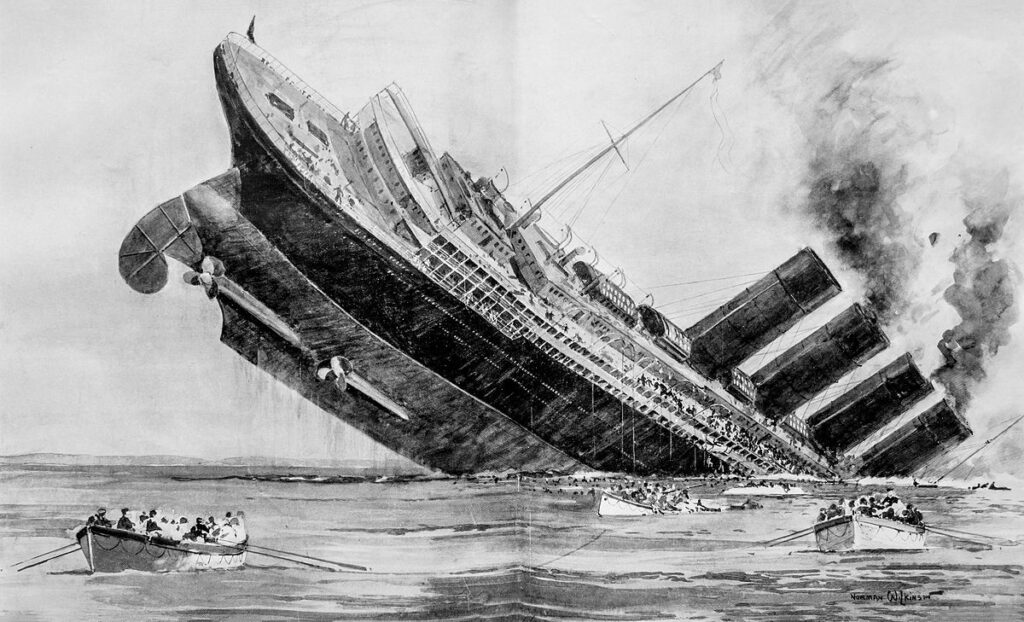

A formidable naval power, Britain entered the Great War with a somewhat lofty confidence, which was not meant to last. Having tried and failed to measure up to the Royal Navy, the German Admiralty had redrafted its strategy for the new century, investing heavily in a novel but promising technology – the submarine. The results were deadly. On 7 May 1915, the RMS Lusitania was attacked and sunk by German submarine U-20 off the coast of Ireland, killing 1,198 of her 1,962 passengers. By 1916, one in every five British supply ships in the English Channel fell victim to German torpedoes. The ease with which Imperial U-boats took out British vessels became even more alarming with Germany’s declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare. By the end of the war, U-boats sank more than 5,000 ships and killed nearly 13,000 men. In early 1917, while many on the British Isles followed the carnage with despair, one man got creative.

Like many others at the time, marine artist Norman Wilkinson experimented with camouflage techniques, but each new attempt led the British volunteer to the same unsurmountable problems. The first hurdle were the ships themselves – to the trained eye of a gunner, a vessel’s shape, size, and position betrayed her direction and speed within seconds. Moreover, unlike forests and deserts, the sea offered no suitable background for an object to blend in, the volatile weather conditions constantly altering light and cloud patterns. But as Emperor Wilhelm’s underwater assassins turned the ocean into a slaughterhouse, sinking 23 British vessels on average each week, Wilkinson could not afford to fail.

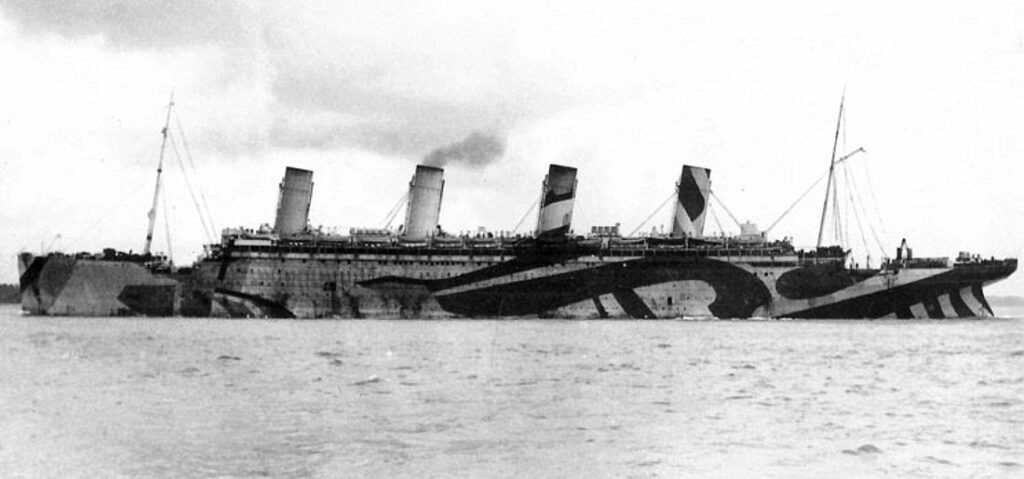

In 1917, the talented reserve officer decided to turn the problem on its head – instead of evading the enemy, why not confuse him instead? Wilkinson began by covering model ships with irregular and contrasting geometrical patterns, so that shape, size, and direction were hard to determine from a distance. In some designs, he painted a fake bow on the side of the hull, in others he made the front seem like the back, or visually broke up the stern to make the vessel look shorter. The most befuddling combinations used blue stripes to make one large ship look like several smaller ones. All this could cause a gunner to miscalculate the trajectory of his torpedo by a few degrees, enough for a miss or a less damaging strike.

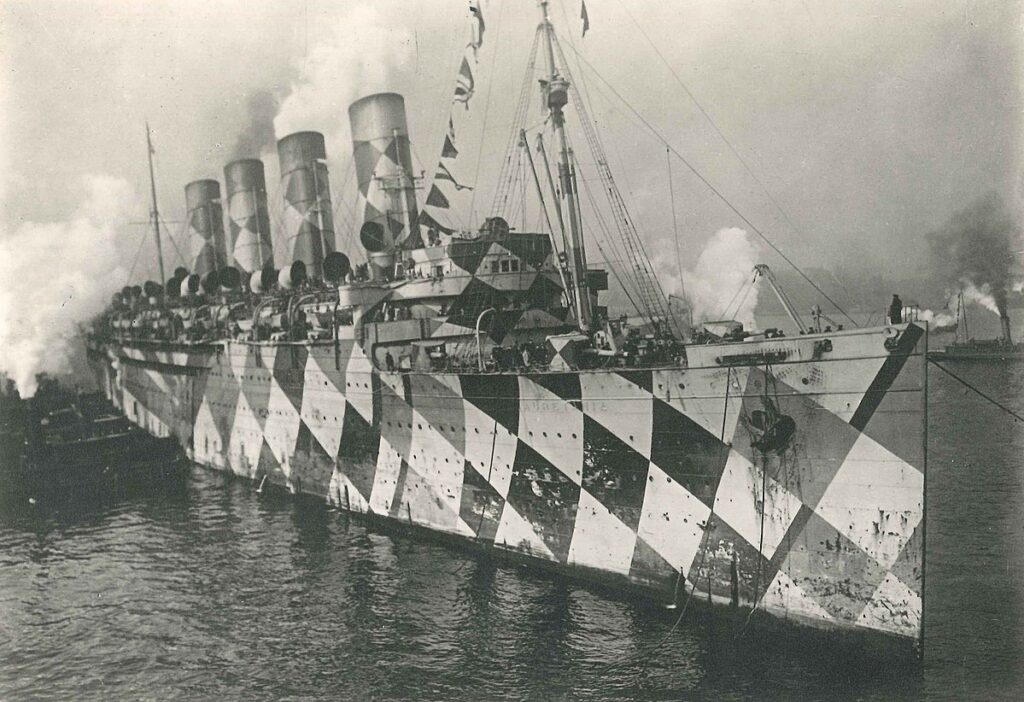

Wilkinson called this game of smoke and mirrors ‘dazzle camouflage’, dubbed by many ‘razzle dazzle’. The experiment, outrageous at first, was effective enough to convince King George V to give his royal blessing. The British Navy’s Dazzle Section was a go.

The first ‘dazzler’ was the HMS Industry in 1917. Within less than a year, Wilkinson’s team (staffed mostly with talented women from the Royal Academy of Arts) designed the camouflage of more than 2,000 British ships – conspicuous enough to make an impression across the Atlantic, where the USA had already failed several disguising attempts. The Americans had the additional problem that many of their troopships were seized German vessels, hence, even more recognizable to the enemy. After demonstrating his invention to the admirals in Washington, Wilkinson was invited to share his know-how with the US Navy, partnering with American expressionist artist and fellow reserve officer Everett Warner.

Curiously, the inventor of ‘dazzle’ had no love for contemporary art. Indifferent to the likes of Picasso and Braque, Wilkinson was a traditional marine painter and illustrator, preferring tame seascapes and dramatic naval battles to the ‘savagery’ of cubism and abstraction. Still, his bold camouflage designs were so reminiscent of modern art, that Picasso reportedly joked about having invented them himself.

Artistic anecdotes aside, razzle dazzle gained such popularity with naval top brass that, by the end of the war, more than 4,000 British vessels were camouflaged by Wilkinson’s unit. In hindsight, though, the effectiveness of the invention was controversial. The Navy determined that reductions in fatal strikes had been marginal, although comparisons with non-camouflaged ships proved tricky. First, each design was so unique that its effectiveness could only be evaluated on an individual basis, rendering generalized conclusions irrelevant. Second, ships with dazzle patterns were more visible to submarines and got attacked more frequently but were less often damaged or sunk. And finally, however small the effect may have been, human life is priceless, and if this bizarre form of art saved even one soul from the bottom of the sea, then it was well worth it.

The Shipyard

P.S. Missed the previous post? Read it here.