Shanghai, the busiest port the world has ever seen, may also be the oldest in existence. The tiny fishing village sprouted out of the marshy soil on the banks of the Huangpu River and, with the persistence of a weed, survived over 7,000 turbulent years before the mighty wheel of fortune put it at the top of global trade. Having kept a low profile through most of its history, as though saving its strength for the right moment, Shanghai is now China’s cosmopolitan gate to the world and one of the cornerstones of its economic growth. Contrary to its flashy present, the port city has had a bumpy ride to the top – a story as inspiring as it is controversial.

Roots Run Deep

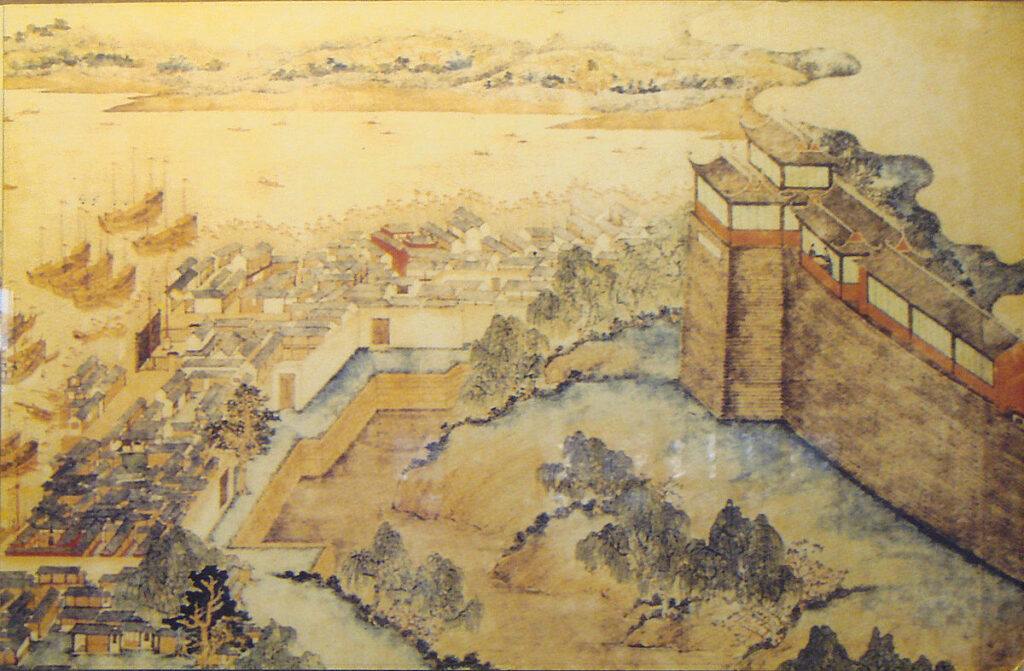

The oldest discovered settlement in the area dates to 5,000BC, but the village only gained fame around the 4th century CE. It was then known as Hu, a name derived from the special fishing traps the locals used near the mouth of the Yangtze. It must have been an important-enough invention, for it is still one of the symbols of the modern city. But it took almost a millennium and a stormy Mongol conquest, until the villages around the Yangtze estuary were fused together to form the city of Shanghai and participate in the growing shipping industry. The year was 1291, and Genghis Khan’s grandson Kublai ruled a mega-empire out of Beijing.

As Mongol rule fell apart less than a century later, the Ming emperors saw Shanghai’s real strategic potential for international, coastal, and inland trade. Not only did it control the access to Asia’s longest and most important navigable river, but its geographic characteristics made it ideal for a major port. Completely flat and interspersed with numerous waterways, it was also the only ice-free port in the northern half of China – perfect for year-round navigation, logistical infrastructure, and unlimited expansion. As a result, records from the time indicate that most of the city’s 300,000 inhabitants were employed in shipping.

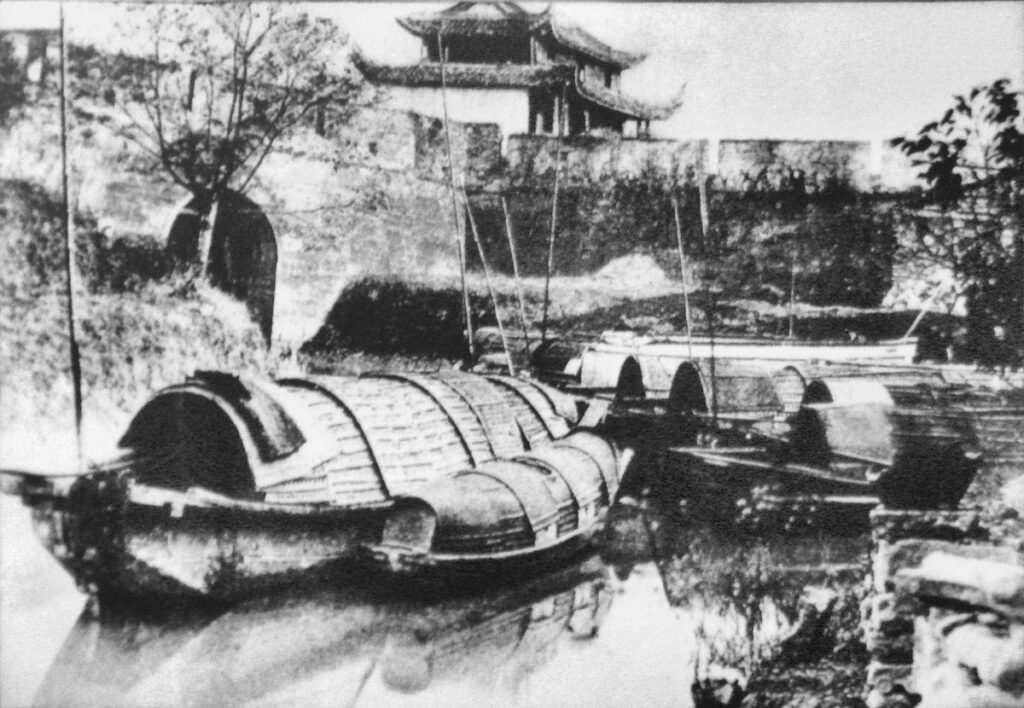

Shanghai’s fortunes in the following centuries swung between prosperity and hardship, as the port’s development often attracted Japanese pirates. After some devastating raids, the Ming emperors unleashed a decade-long campaign against the daring marauders, annihilating most pirate-fleets and restoring unobstructed maritime trade. Another menace, however, was not so easy to deal with. In the coming centuries, it would lavish Shanghai with immense riches and cause it terrible calamities.

The West Sails East

The first European in Shanghai to leave a historic footprint was Jesuit monk Matteo Ricci, famous for compiling the first Sino-Portuguese dictionary in the early 1600s, which helped open doors to cultural and commercial exchange between China and the West. But despite Shanghai’s strategic location, European trade in the next 250 years flowed through nearby Zhoushan, and after 1760 – exclusively through Guangzhou under the Canton System. And even though Shanghai remained an export hub for textiles and fertilizer to India and Persia, political restrictions deprived the port of its share in the silver from Spanish South America, brought on the legendary Manilla Galleons. In the light of China’s 19th-century demise, many argue this may have been for the better.

Victim of Western Drug Cartels

One of China’s greatest opportunities turned out to be its curse – Britain fell in love with tea. From an exclusive treat for the rich and noble-blooded, this traditional Chinese beverage took the Isles like a typhoon. At one point, tea became such a predominant commodity for British merchants that their elite clipper-fleets were chiefly dedicated to carrying it across the oceans as fast as their sails would allow. The Middle Kingdom was an endless source of tea, the British market – a vast source of profits. The only problem: payment.

After the influx of Spanish precious metal in Asia, Beijing decided to only export goods in exchange for silver, creating a huge problem for the British, who did not have enough of it to sustain the booming trade. But crafty colonial magnates soon came up with the ‘perfect’ solution – they sold Indian opium to Chinese dealers, generating more than enough silver to finance subsequent purchases of tea. The result was nothing short of an opium epidemic, as Chinese society sank into addiction. Of course, drugs were illegal in both Britain and China, but since laws and morals never stood in the way of profits, merchants soon gained enough power to dictate policy measures to the parliament in London.

Appalled and outmaneuvered in this deadly way, Beijing made a desperate attempt to seize and destroy opium stocks in Guangzhou, only to find itself embroiled in what became known as the First Opium War. There were two of these, and China lost both. The result – a series of unequal treaties, in which the Qing Emperor was forced to not only lift restrictions on foreign trade, but to offer Britain and other Western powers preferential treatment. Several ‘treaty ports’ were established for the new trade, and Shanghai, with its population of 500,000 and strategic access to the manufacturing hinterland, was one of them. Britain’s “Gunboat diplomacy” gave rise to a new age – golden for some, dark for others.

“Paris of the East”

As a treaty port, Shanghai’s multi-national core was divided among Britain, France, Italy, the United States, and (later) Japan. Positioned at key locations at the Huangpu River and Soochow Creek, the foreign concessions enjoyed extra-territorial status and freedom of trade, leading to the creation of advanced port facilities, enormous trading houses, financial institutions, and even their own police force. In the early 20th century, as tea clippers gave way to iron steamers, the Xinhai Revolution replaced the humiliated monarchy with a volatile republic, and the lively port town of Shanghai grew into a dazzling megapolis.

With the rapid accumulation of wealth among the city’s merchant class, the foreign enclaves gained an increasingly Western façade. Straight avenues replaced winding alleys, Art Deco high risers rivalled New York and Chicago, and the new riverfront hotels surpassed even Paris in their lavish luxury. The glamour of Shanghai could only be matched by its depravity, with the “roaring twenties” lasting well into the thirties – a powder keg of money, crime, and social tensions.

The Giant Steamers Arrive

Between the world wars, major steamship lines hurried to include the new and glorious Shanghai in their Far Eastern voyages, bringing scores of European and American tourists to the “Paris of the East”. Following the British and Hong Kong shipping tycoons, overseas lines raced to open their offices in the city – the Dollar Steamship Company and Pacific Mail Steamship Company from the USA, the French Messageries Maritimes, the Dutch Java China Japan Line and Royal Interocean Lines, the German Norddeutscher Lloyd, Canadian Pacific, Australian Oriental Line, the Japanese Nippon Yūsen Kabushiki Kaisha, and many others.

The formidable hulls of ocean liners became an increasingly common sight, surrounded by the junks and sampans crowding the bustling harbor. More than 40,000 tourists a year visited Shanghai in the 1930s – a staggering number, considering the troubled Chinese affairs at the time. The former empire was barely standing on its feet, fighting a civil war between Mao’s communists and Chiang’s nationalist government, as well as suffering the consequences of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Such dramatic contrasts were to define Shanghai in the glorious and tragic thirties.

Steamers surged from all corners of the world, unloading cargoes of glitter and despair. In 1936, the Dollar Line’s SS President Coolidge brought the brightest Hollywood star to China – it was in Shanghai that Charlie Chaplin revealed his engagement to actress Paulette Goddard. He was so impressed he even considered moving to China permanently. But this trip also opened Chaplin’s eyes to Shanghai’s less-fortunate visitors – the 35,000 Russian refugees, chased out of their homeland to find shelter in this Wild East. Since the Russian Civil War, numerous emigres had been pouring into the freeport on naval steamers, passenger ferries, and even boats. The plot of Chaplin’s film A Countess from Hong Kong (set on an ocean liner), was the result of this troubling encounter.

As the Nazi and their allies tightened their grip around Europe, a new wave of asylum seekers flooded the foreign concessions. The first Jewish refugees arrived in 1938 on the SS Usaramo, a former liner of the German East Africa Line on her way to the scrapyard in Japan. And with the Holocaust gaining its monstrous momentum, many Jewish fugitives spent their last money on tickets to China. Many travelled on the famous Japanese Hikawa Maru (currently docked at Yokohama and serving as a museum) and her sister Heian Maru. Before Italy joined the war in 1940, some 17,000 Jewish refugees arrived on Lloyd Triestino steamers, including the beautiful but ill-fated SS Conte Verde, which remained permanently in Shanghai until its scuttling in 1943.

The port’s refugee crises did not end with the war, culminating with the SS Kiangya disaster in 1948. The small steamer carried over 4,000 Chinese, displaced from one of the deadliest civil wars in history. On her way out of Shanghai, she struck a leftover Japanese mine in the Huangpu River and sank with a shattered stern. Sources report up to 3,900 casualties (surpassing the Titanic by 2.5 times), making the Kiangya incident the deadliest non-combat maritime disaster until then.

A Turbulent Peace

With Mao’s victory in 1949, China got the peace it so desperately needed but at the price of international isolation, social instability, and economic decay. In response to the PRC’s support for the Korean communists, the United States imposed a trade embargo from 1950 to 1972, limiting Mao’s major trading partners to one – the USSR. In addition, the United Nations took twenty-two years to recognize the People’s Republic, while the World Trade Organization kept Red China out of mainstream global commerce until 2001. In the meantime, Far Eastern shipping routes were redirected from Shanghai to Hong Kong and Singapore, leaving behind a couple dozen dilapidated steamers. From one of Asia’s leading ports, the city became a regional backwater – the gateway to a country with nothing to sell and no money to buy.

Despite its modest needs, the PRC had a tough time scraping together a useful fleet. National shipping was divided in three regional administrative entities – North, East, and South – but the former two were soon amalgamated into the Shanghai Maritime Bureau. The centralized running of ocean, coastal, and river lines was no easy task, especially with the Party’s hesitations between purchasing foreign vessels or building its own. To stay afloat, the Shanghai Maritime Bureau did both. Notable tramps built in Shanghai were the 13,500-ton Dong Feng (1960) and the 10,000-ton Feng Qing (1973). And while local shipyards struggled with limited capacity, foreign acquisitions proved just as complicated, most of them carried out through Hong Kong “front” companies or Western intermediaries like the Wallem agency in Shanghai.

The Giant Returns

Richard Nixon’s visit in 1972 was a major public step in the Red China’s acceptance into the international community, while Deng Xiaoping’s ascent to supreme leadership ten years later triggered unseen economic growth. China’s transformation into a global exporting power triggered staggering development in the shipping industry, of which the port of Shanghai was the natural champion.

From the jumble of dysfunctional state-owned shipping lines rose one of the leaders in global maritime freight. In 1997, the Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Dalian conglomerates merged to form the Shanghai-based China Shipping Group, which in turn merged with the China Ocean Shipping Company to form the behemoth COSCO Shipping. Headquartered in Shanghai (with parent group in Beijing), the company runs one of the largest commercial fleets in the world with more than 1,300 vessels, among which the giant container ships of the Constellation and Universe classes.

To accommodate the monstrous new fleet, the port facilities underwent rapid expansion between 1991 and 2005, the result of which was the world’s largest port by throughput, surpassing Singapore in 2010. 25,000 container ships pass through every year, carrying more than 40 million TEU. Categorized as a port-megacity, Shanghai has 125 docks and 19 terminals, including a cruise terminal for one million passengers a year and a RoRo terminal for 1.2 million vehicles annually. A 32.5-kilometer cross-sea bridge connects the deep-water port in Hangzhou Bay to the Pudong business district, with a new Shanghai-Ningbo bridge in the planning. All this is backed by the momentum of the world’s second largest economy, dead set on becoming number one. And even though the road ahead is shrouded in uncertainty, Shanghai’s persistence over the last 7,000 years shows us without any hesitation that this port is here to stay.

The Shipyard

Beautifully written article. I learned many new, exciting details about the history and development of Shanghai. Thanks for the shared knowledge.

Thank you for reading it!

I am a intermodal truck driver and have an immense fascination with world trade history this was fantastic reading

Thank you for your kind comment! Trade history is one of my soft spots too, and I really enjoyed writing this.