Oil was among the cornerstones of the 20th century and continues to be a prevalent energy source so far in the 21st. Glorified by some and demonized by others, this liquid fossil-fuel has defined global political and technological processes for more than a hundred years. And despite decreasing popularity, few things symbolize the golden days of crude oil better than the supertanker. Though ultimately a short-lived trend, supertankers were the result of long-term economic, political, and technological developments.

From Floating Barrel to Oil Tanker

Early designs were plagued by inherent instability due to the free surface effect, with the oil sloshing to the sides of the hold in the same direction as the rolling of the ship. This neutralized the righting effect of displaced water outside the hull, changing the center of gravity enough to capsize the vessel. In 1883, British engineer Henry Swan tried sectioning the cargo holds of the Nobel tankers Blesk, Lumen, and Lux – a principle so effective it still defines modern tankers. Swan then used his concept to design what many consider the first purpose-built oil tanker, the Glückauf (1886). In addition to divided holds, she had a direct filling system, horizontal bulkheads, and a ballast system to replace oil with seawater when unloaded.

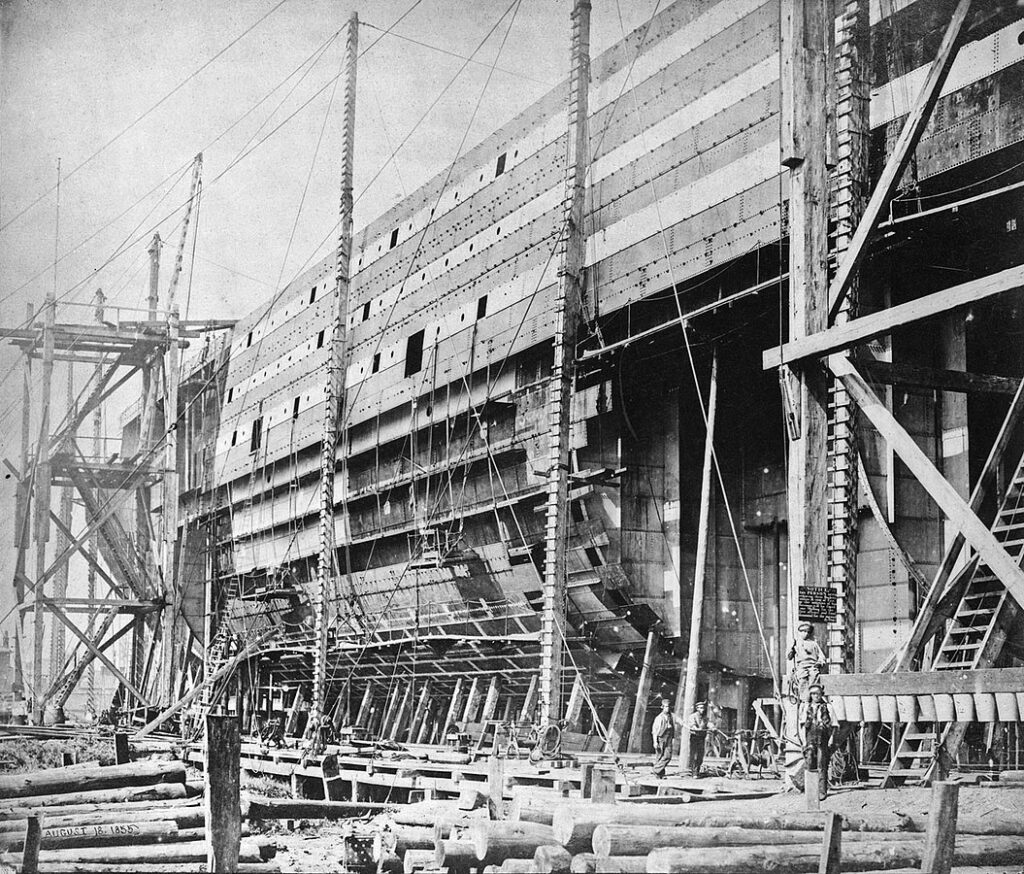

The second development to expedite the birth of supertankers was longitudinal framing, in which the heavy transverse frames are reinforced by light longitudinal members. Despite the existence of longitudinally framed ships in the late 19th century (most notably, Brunel’s Great Eastern), the process only became economical through Joseph Isherwood’s 1906 patent, allowing for much longer cargo vessels, without compromising structural integrity. The successful 1908 prototype Paul Paix encouraged shipbuilders and owners to adopt the technology and produce longer and safer oil carriers.

The third design milestone came about in the 1950s, with shipbuilders moving away from the “three-island” profile (forecastle, midship, and poop deckhouse) to produce the streamlined tanker we know today. The new concept moved the navigation-bridge and crew quarters to the aft, which not only improved the practicality of the ship’s layout but made construction and operation much cheaper.

The Suez Bottleneck

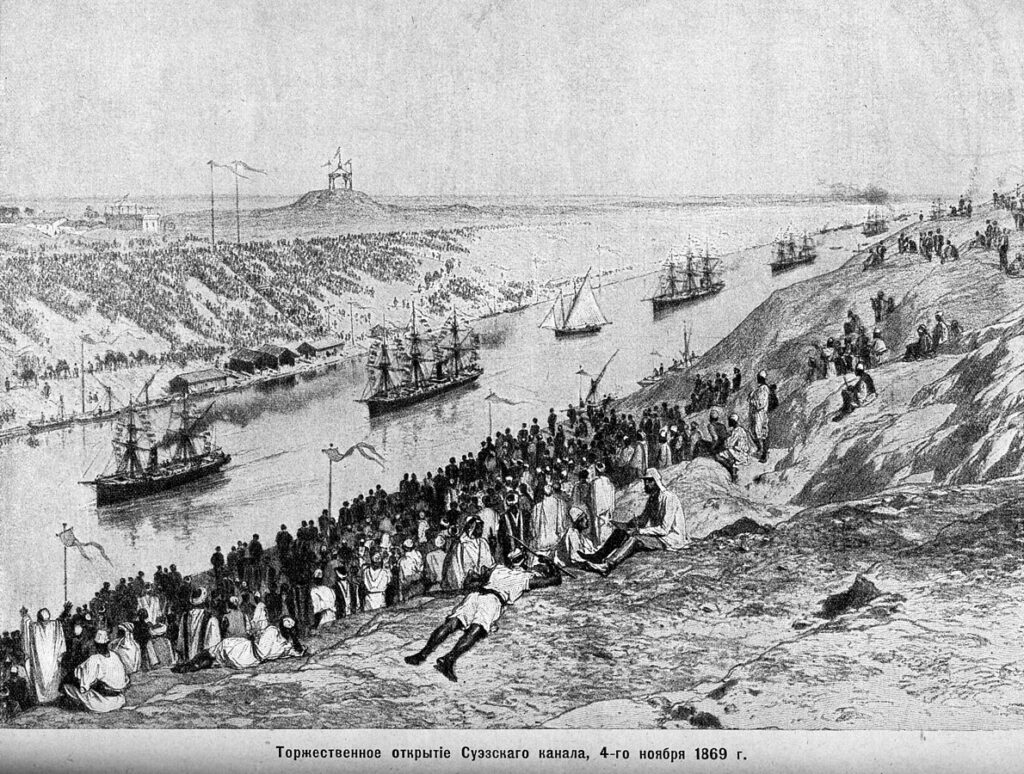

As it turned out, design problems were easier to resolve than infrastructure challenges, the most important of which was the Suez Canal. When an oil tanker first sailed through it in 1892 (Shell’s Murex), draft was not yet an issue, but as longitudinal framing quadrupled the size of the average tanker, the Canal’s 8-meter depth threatened to turn into a bottleneck.

WWII: The Great Accelerator

As with many modern technologies, the Second World War’s monstrous scale was the decisive trigger for the development of supertankers. The T-2 class of turbo-electric oil tankers was a pioneer not only for its all-welded hull, but also for being entirely made of standard components. This unlocked the potential of mass-production, leading to the completion of 533 tankers in the last five years of the war.

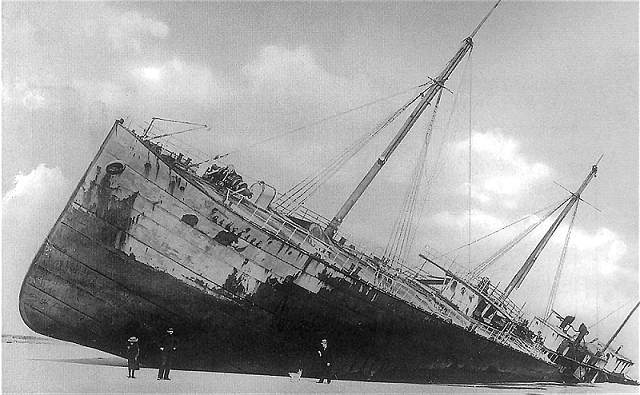

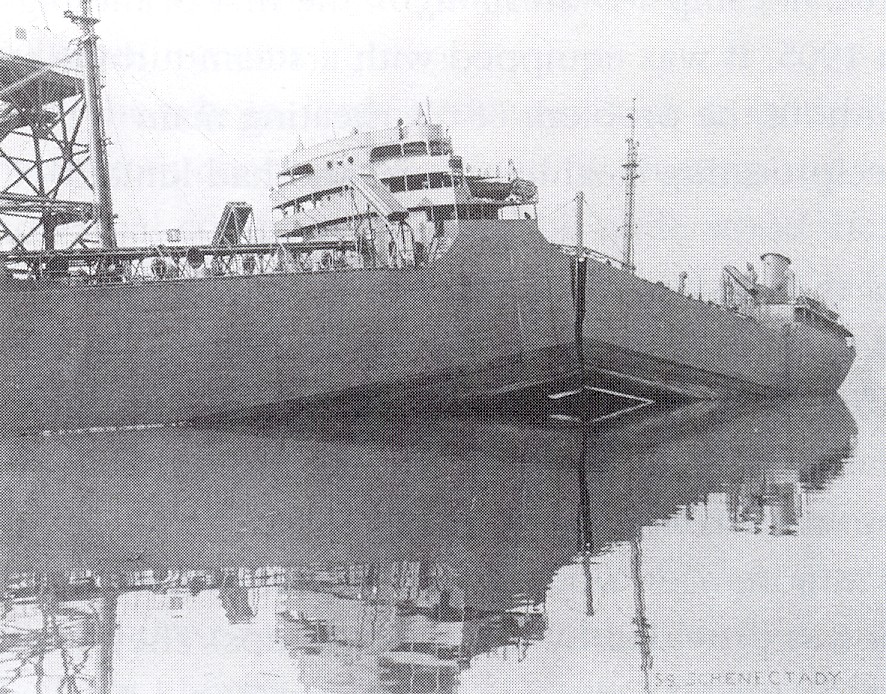

Early T-2s suffered from structural weaknesses, like the SS Schenectady, which broke in two while still in dry dock. Ambiguous naval studies lay the blame on electric welding (then still a novel technology), but engineers soon proved that the problem resulted from the brittleness of the notch-sensitive steel used at the time. Mild steel contains mineral impurities, forming areas of high stress concentration that lead to cracks. The problem was effectively solved with the use of crack arrestors (or rip-stop doublers), a method still used in multiple sectors today.

The Supertanker Boom: Rebuilding a World

Raising the world from the ashes of war led to explosive economic growth in the following three decades. To fuel the boom, companies had to ship staggering quantities of oil from the Middle East to the gluttonous markets of Europe and North America. And while a general undersupply of cargo capacity was beginning to show in the early 50s, one unexpected event made supertankers an urgent necessity overnight.

In 1954, a staunch Arab nationalist took the reins in Egypt, a nation fed up with a turbulent history of colonial rule. As part of his assertive anti-Western approach, Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal on 26 July 1956, infuriating Britain and France. In response, Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, followed close by French and British paratrooper-attacks. During the hostilities, Nasser ordered the sinking of 40 ships in the Canal, leading to a six-month blockade of all maritime traffic. This crisis was only a foretaste of the coming disaster – in retaliation to the Six-Days War in 1967, Egypt closed Suez again for the next eight years. The only alternative was the 5,000-miles longer route around the Cape of Good Hope.

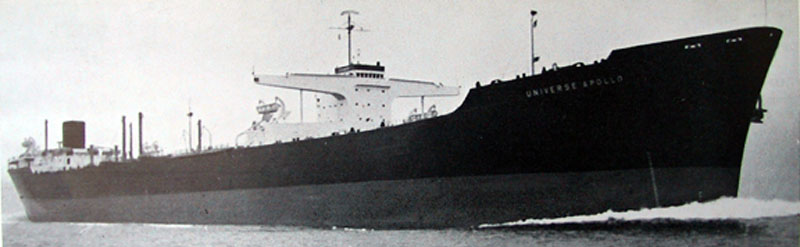

But from these challenges rose a big opportunity – longer journeys called for more and larger tankers, prompting companies to expand their fleets. The title of “supertanker” was first given to the 45,000 dwt Tina Onassis, built for the Greek magnate in 1953 by the Howaldtswerke (formerly Vulkan) in Hamburg. The following year, Onassis one-upped himself with the 47,000 dwt Al-Malik Saud Al-Awal, and so the trend continued, with tonnage rising exponentially over the next twenty years. In 1958, Daniel Ludwig first crossed the 100,000-dwt mark with the Universe Apollo – a huge achievement at the time, but negligible only a few years later.

The 1960s also gave rise to Japanese shipbuilders, whose streamlined manufacturing processes achieved lower costs and shorter construction times. And so, with Far-Eastern shipyards on the scene and Western economies in an oil-fueled frenzy, the age of behemoths had arrived. In 1966, the Idemitsu shipyards built the first Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) – the 209,413 dwt Idemitsu Maru. Only two years later, Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries in Yokohama delivered the first Ultra Large Crude Carrier (ULCC), the Universe Ireland with deadweight tonnage of 331,825 dwt.

The trend peaked in the late 1970s, giving birth to giants like Nai Genova (409,000 dwt), Esso Atlantic (508,000 dwt), the four Batillus-class tankers (555,000 dwt), and the unsurpassed Seawise Giant (657,000 dwt). The latter was renamed several times – Happy Giant, Jahre Viking, Knock Nevis, Mont – and was famously sunk during the Iran-Iraq War in 1988. With nearly 500 m in length, she was the longest ship ever built and remains the largest oil tanker in history. To accommodate these and many other leviathans, several of the world’s major ports, including Rotterdam and Genova, underwent enhancements in depth and handling capacity. Some companies even discussed the construction of a million-ton tanker, but the boom was beginning to subside, and the Seawise Giant’s record remained untouched.

The Bubble Bursts

The 1970s began badly for the oil industry, with Western companies losing much of their bargaining power, leading to complete nationalization of the oil sector throughout the Arab world. The 1973 Yom Kippur War with Israel led to further dissatisfaction in the Middle East, culminating with OAPEC’s notorious oil embargo. The 1973 oil crisis triggered petroleum companies to diversify their operations globally. One result of this effort was the discovery of new oilfields in the North Sea, Alaska, Canada, and Mexico – all located relatively close to major consumers and able to deliver via pipelines or smaller fleets. This not only reduced overall demand for shipping but also highlighted the limitations of supertankers.

New market realities required flexibility, and when smaller and cheaper ships returned to the scene, the overtonnage crisis was impossible to hide. By 1984, nearly 20% of the world’s tankers were redundant, while many of the active vessels were employed in unprofitable activities. With freight rates at bottom levels, many operators went bankrupt, while others reduced the share of VLCC’s and ULCC’s in their fleets. Under such unfavorable conditions, oil companies relinquished their shipping activities to charter operators, who could neither afford nor had much use for supertankers. A golden age was coming to an end.

An Uncertain Future

Today’s oil industry is as volatile as ever, with unpredictable changes happening on a regular basis. And while supertankers are still the backbone of long-distance transoceanic trade, companies are more conservative in their investments. The world has changed since the 1970s, with new economic powerhouses emerging over the years – South Korea, Brazil, Mexico, India, Southeast Asia, and China – shaping new priorities for shipbuilders and operators. With the focus shifting from economy of scale to safety and environmental sustainability, developments like double hulls and energy efficiency have been far more important than size. And as the world slowly moves away from fossil fuels, it is unlikely that we see another Seawise Giant in the future.

The Shipyard