Split between the most abandoned corners of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, lies a forlorn desert, one saltier than the ocean. Not a single path runs through the horizonless plain, and not even the buzz of an insect disrupts the eerie, sunbaked silence. The only lifeform that the naked eye can distinguish is the occasional fox, hunting for gerbils among dried-out, dusty shrubs. It is inconceivable to the imagination that here at this spot, not long ago, the fourth largest lake on earth glittered under the sun – the Aral Sea. Fed by the Amu Darya river in the south and the Syr Darya in the north, it once stretched over 69,000 square kilometers and was home to over 20 different species of fish, its richness and biodiversity providing the livelihood of some 40,000 fishermen.

In the middle of the 19th century, the Aral Sea became a strategic asset for the Russian Empire. The Tsar used it to expand his borders into Central Asia by commissioning a brand-new naval fleet, known as the Aral Flotilla. The fleet was officially set up between 1852 and 1853 with the purpose of carrying troops during colonial expeditions, delivering supplies, enhancing trade, as well as protecting the coastal areas of the Syr Darya. But it all began in 1847, when the wooden two-masted schooner Nikolai was built in Orenburg, a city on the outer edge of Siberia. Once completed, the vessel was taken apart for the thousand-kilometer journey through the steppe, and then reassembled upon reaching the Aral Sea. Intended as a war ship with its two guns, the Nikolai was 11.73 m long, 3.56 m wide, and had a draft of 1.65 m. That same year, a second two-master, the Mikhail, was added to the Aral Flotilla, but unlike the Nikolai, the Mikhail was planned to operate as a merchant ship in local fisheries. The design of both ships, however, proved impractical for the largely shallow waters of the giant lake, and the two ended up carrying out rather limited surveying assignments.

In early 1848, Lieutenant Aleksey Ivanovich Butakov was appointed to lead the first Russian naval expedition to the Aral Sea, the purpose of which was to photograph, survey and record the geography of the area. A special schooner with a crew of 27 men made the expedition possible – the Konstantin. She was again built in Orenburg and delivered by land to Fort Raim, a small fortification about 60 km from the mouth of the Syr Darya. The ship was 14.33 m long, 4.88 m wide, and had a draft of 1,85 m. One of the men on board was the exiled Ukrainian writer and artist Taras Shevchenko, assigned the task of sketching the coastal landscapes. During his 18 months aboard the schooner, Shevchenko documented the entire expedition with his drawings and paintings of the area. The expedition was a success, producing the first reliable maps of the Aral Sea.

Four years later, Butakov delivered two iron steamships to Fort Raim – the Perovsky and the Obruchev, both built in Sweden and specifically designed with a remarkably shallow draft. Like their predecessors, they travelled to the small hilltop fort in disassembled form. Due to the lack of coal in the area, the new steamers were designed to burn saxaul, but due to its fast burning rate, this desert bush proved inefficient as fuel, and coal had to be procured from far-away regions at premium price. Although expensive, this proved to be the right decision, considering the important role the two ships were to play in future battles.

In 1853, the Perovsky aided the capture of the Kokand fortress Ak-Mechet by transporting men, supplies, and military equipment along the Syr Darya. Later on, during the takeover of the Kokand and Bukhara regions between 1864 and 1868, both the Perovsky and the Obruchev served as military vessels. The two ships proved useful again in 1873, when Russia fought and conquered Khiva.

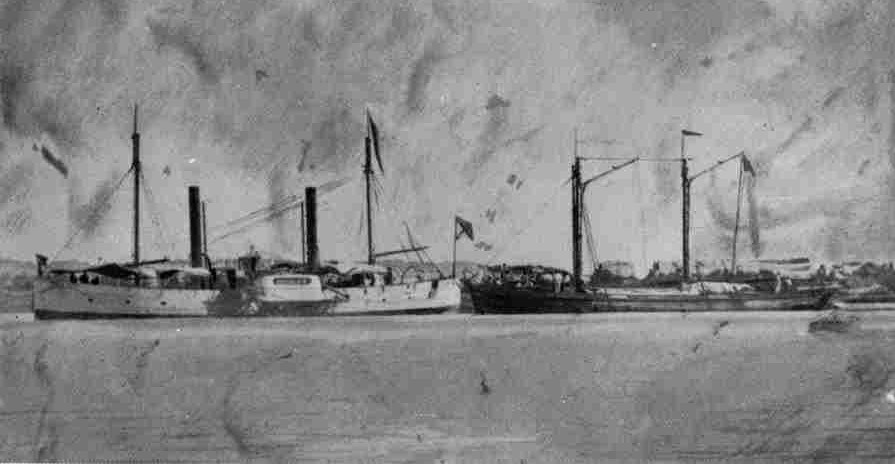

(July 1858)

Two additional steamers joined the Aral Flotilla in 1861, the Aral and the Syr Darya, both with iron hulls and built in Liverpool, England. Five years later, the Samarkand was built in Belgium and specifically designed with a paddle wheel at the bow, allowing her to maneuver both forwards and backwards – a major advantage over the other Aral Sea ships. A much larger vessel (her length was 45.72 m, with a 6.7 m beam, and draft of 0.61 m), she could accommodate a crew of 2 officers and 50 lower ranks.

The Aral Flotilla was an important instrument in the Russian Empire’s expansion into Central Asia, but from 1880 onward, the fleet began to break apart. The main reason for this was that a regular shipping service along the Syr Darya turned out uneconomical. The shallow and unpredictable waters of the river made it difficult to navigate, turning ships with a higher draft into expensive but useless assets. At the same time, vessels that could handle the shallow waters were extremely slow.

Attempts to reestablish the fleet were renewed by the Red Army in the early stages of the Russian Civil War to aid its efforts against Tsarist troops. The fleet, however, became obsolete after the Communist victory, and with the rise of the Soviet Union came the demise of the Aral Sea. The main reason, as usual, was money. A water-intensive crop, cotton was a traditional product of Central Asia, and with the introduction of long-fiber varieties during the monarchy, the region’s “white gold” became a global commodity. This resulted in a monoculture economy, entirely based on cotton – a death sentence for the Aral Sea and any dreams to revive navigation on it.

In the 1930s, Moscow went ahead with its “cotton independence” strategy, which saw the building of canals to divert fresh water from the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya rivers and irrigate nearby deserts to turn them into arable lands. The culmination of this Babylonian effort was the 270 km Great Fergana Canal between modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, completed within just six weeks by 160,000 local farmers. A major addition came some fifteen years later, when the USSR began the construction of the Karakum Canal in the Turkmen Desert.

The result was nothing short of a disaster. Due to poor engineering, 80 percent of the 47,750 km canals did not have adequate insulation, resulting in most of the water leaking into the sandy soil before it could reach the crops. From 1960 onwards, the lack of water supply led to the drastic shrinking of the Aral Sea, eventually splitting it into two separate basins, then into four. In the 1980s, its total surface area was a mere quarter of what it used to be.

The extreme salinity of the remaining water led to the extinction of almost all animal and plant species in the sea, bringing an end to the once flourishing fishing industry in port towns like Moynaq and U’shsay. The last fleet to ever sail the Aral Sea, the rusted carcasses of their fishing-boats now lie decomposing on the toxic sand – a monument to human irresponsibility.

The Shipyard

P.S. Do you enjoy maritime history? Have a look here!