There is a reason why the Arctic passage to China is less known than the Silk Road: it never came into existence. But not for lack of trying – in fact, seeking a navigable route along the ice-clogged northern coast of Eurasia was among the most ambitious and dramatic maritime enterprises in history. A Hollywood-worthy tale of courage, grit, and despair, it was the supreme challenge for the toughest of men, lured by the promise of riches, fame, and power. Most perished in an icy grip, and the handful who survived by the skin of their teeth only confirmed it was all a delusion. But now, this may be about to change. As polar ice melts away in the changing climate, the deadly passage north of Siberia may be fully operational by the end of the century. The impact – global trade will change forever.

It Is So Cold, Why Even Bother?

At 3,500 nautical miles, a voyage through the five seas of the Russian Arctic is three times shorter than the 11,000-mile odyssey around the Cape of Good Hope, the only seaborne route from Western Europe to China in the 16th century. But distance was not the only obstacle – in 1494, the Spanish and Portuguese empires signed the (somewhat egomaniacal) Treaty of Tordesillas, splitting the world into two spheres of influence, with Spain taking over the West, and Portugal “pocketing” the East. With the oceans thus divided between the two super-navies, little remained for fledgling powers, such as England, the Netherlands, and Russia. Unwilling to challenge Portuguese supremacy in the Indian Ocean, an Englishman ventured into the cold embrace of the Arctic.

Someone was already there.

Ancient Icebreakers, and Lots of Them

The first to populate the northern coastline of Siberia were the pomors (or “seasiders”), a group of Russian settlers who migrated from Novgorod to the White-Sea coast in the 12th century. To navigate the treacherous waterways, they developed an ingenious sailboat with a double egg-shaped hull beneath the waterline – the koch. A rounded hull allowed the vessel to slide up, escaping the grip of encroaching ice, a design so effective it still defines modern icebreakers. Additional equipment for Arctic service included a unique rudder (slim at the top and extra-wide at the bottom), as well as two auxiliary boats with windlasses to pull the koch out of the water and onto the ice.

As our British gentleman rounded Scandinavia and sailed into the inhospitable waters of the Barents Sea, the square sail of Russian koches was an almost ubiquitous sight, with numbers reaching in the thousands.

Sir Hugh Sets Sail

Although something of a hero in the Eight-Year War, Hugh Willoughby was falling out of favor with Henry VIII. Knowing the temper of his monarch, the soldier turned to the sea. It was 1553, and the opportunity lay further north than any Englishman had ever ventured – a mission to reach the Far East from the north, while also establishing business ties with Ivan IV of Russia. The name of this noble enterprise: Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands.

Things got off to a bad start, though, with adverse weather causing one delay after another, until a severe storm north of Norway separated Willoughby’s ship from that of his first pilot Richard Chancellor. With limited visibility, Sir Hugh and his crew went from one uninhabited island to the next, until the encroaching ice extinguished all hopes for return before the spring.

Meanwhile, Chancellor located the entrance to the White Sea, landing at the village of Nyonoksa to wait for Moscow’s reaction. It came without delay, as Ivan the Terrible, eager to expand his trading network, summoned the Englishman to the capital. Agreements were signed and wine was drunk, but still no news came of Willoughby. It was only after Chancellor’s departure from Moscow that fishermen reported the discovery of a foreign ship with 62 corpses on board near Novaya Zemlya. Chancellor made another successful visit to the White Sea and Moscow, only to perish on the return voyage in 1556.

Enjoying this post so far? I bet you would love The Shipyard Shop for some awesome maritime-themed gifts!

A Very Persistent Dutchman

For a professional cartographer and geographer, Dutchman Willem Barents had a rather experimental notion – heated by midnight sun, the North Pole should be free of ice. Barents set sail to prove his theory in 1594, only to run into scores of massive icebergs west of Novaya Zemlya, a reality-check that almost cost him his life. Still, after fighting a polar bear and killing a few walruses, the crew called the expedition a success and returned to the Netherlands.

Back home, the Prince of Orange was so fascinated by Barents’s stories he ordered immediate dispatch of a new expedition, this time loading the ships with premium Dutch goods for the Chinese market. The cargo never reached its destination, as the awful weather once again extinguished all hopes of sailing past Novaya Zemlya.

The Dutchman’s third voyage, with captains Jan Rijp and Jacob van Heemskerk, would be his best and worst. Crossing into the Arctic, Barents made the important discovery of Svalbard, where friction between him and Rijp erupted into a complete breach. Rijp sailed northward, convinced that the shortest route over the North Pole would also be the easiest, while Barents continued toward Novaya Zemlya.

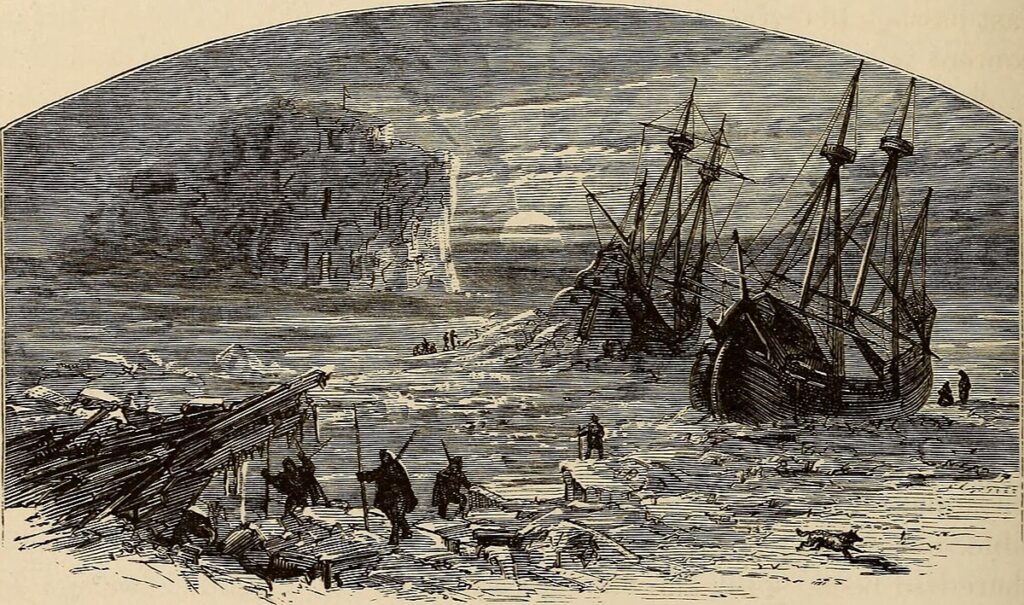

Ironically, Rijp’s overconfident decision saved him, as the ice proved impenetrable early on, forcing his return to the Netherlands. Barents was not so lucky, and although he maneuvered south toward the Vaigach Strait and the Kara Sea, the dense floes clamped around his ship, and the journey was over. The crew dismantled the vessel to build a shack for the ferocious winter, but the cold was only one of many dangers. Exhausted by scurvy, Barents died in June 1597, less than two months before the remaining 12 survivors were rescued by Jan Rijp.

Bering vs. Dezhnyov – Whose Strait Is It Anyway?

The Age of Discovery was all about who arrived first, and one of the hottest disputes in the history of the Northeast Passage is who first sailed through the Bering Strait. “Who else but Bering,” most of us would wonder, but a less-known Russian explorer had sighted the narrow waterway 80 years earlier.

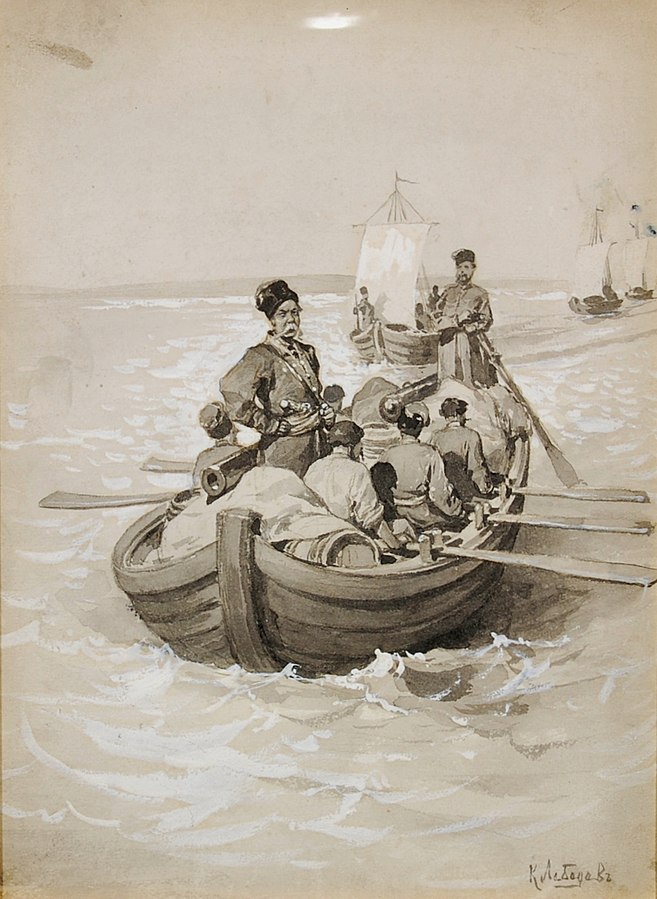

Semyon Dezhnyov, a government official in remote Yakutia, was more interested in sable furs than geographical discoveries. As part of a hunting expedition in 1648, he sailed down the Kolyma River to the Arctic, where six of the group’s seven koches were lost to gales, ice, or belligerent Koryak tribes. Rounding the easternmost cape of Asia, which now bears his name, Dezhnyov sailed into the Pacific, only to have his koch wrecked by a storm. He did not let adversity distract him from the mission – the first thing Dezhnyov did in the new lands of the Russian Empire was to slaughter thousands of walruses and return to Moscow with five tons of tusks. Paling next to this fortune, the report of his discovery remained buried in a clerk’s desk until 1736, eight years after Bering had taken all the credit for proving that Asia and North America were separate landmasses.

On His Majesty’s Arctic Service

Peter the Great remained a controversial figure in Russian history, but few can deny his sweeping scale. Perhaps the first cosmopolitan Russian monarch, Peter hired numerous capable sailors from abroad to staff his fledgling Imperial Navy. One of these recruits was Danish officer Vitus Bering. The young man quickly gained popularity in naval circles, until the emperor handpicked him for a grueling mission to Kamchatka in 1724. But as Arctic winds hampered the expedition, Bering and Peter prepared for a second one.

As always, the Tzar had a bold vision – as if mapping the empire’s Far East was not ambitious enough, Bering was to prospect the shores of Alaska and confirm if Russian merchant ships could reach Japan and Spanish America. Unfortunately for the Dane, now approaching middle age, Peter died in 1725, leaving the expedition on standby.

Fifteen years later, Bering was finally back in Kamchatka, landing on the southern shores of Alaska in the summer of 1741. The crew, drained from the arduous trans-Siberian journey and the rough seas, was eager to return home, but scurvy killed almost half of them just miles away from salvation. Bering himself found his final resting place on a desert island, a stone-throw from the Kamchatkan coast.

Finally, a Breakthrough

Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld did not give a hoot about a life of comfort. Born in Finland in 1832 (then part of the vast Russian Empire), his seditious political activities earned him a speedy expulsion to Sweden. In exile, he harnessed his boundless energy towards a career in adventure and exploration. In 1877, with financing from King Oscar II and some private investors, Nordenskiöld purchased the 60hp steam-powered whaler SS Vega and had her equipped with the latest technologies for Arctic service, including a reenforced hull and an impressive kitchen to maintain morale in tough times.

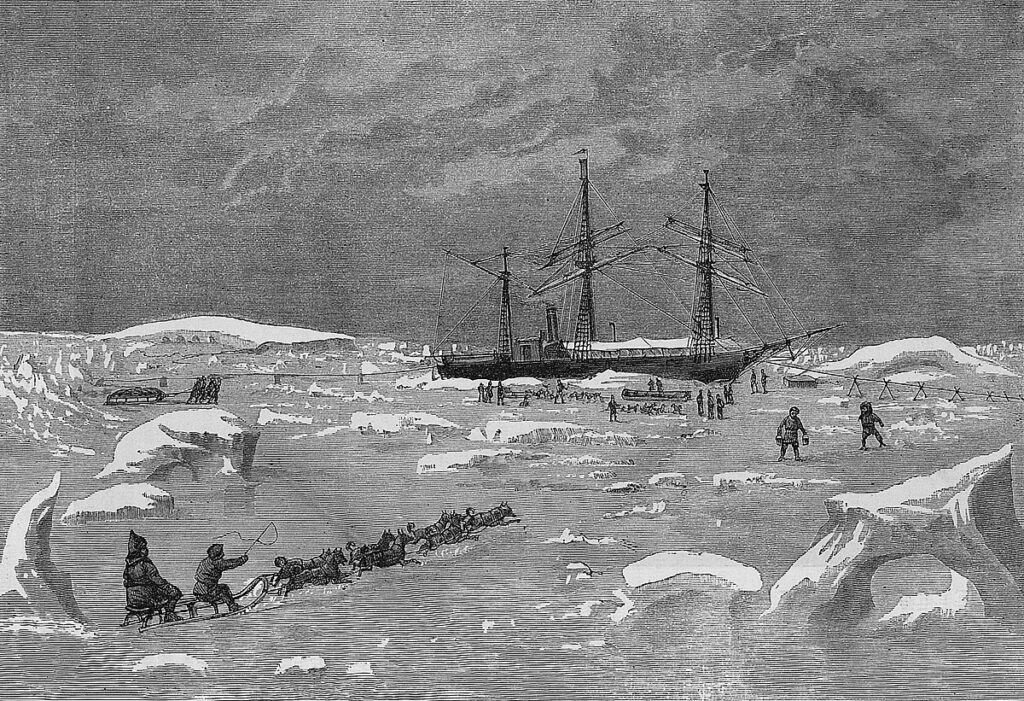

The following summer, the expedition left Stockholm, sailing close to the Siberian shore through narrow passages in the floes. 120 heart-breaking miles before reaching the Bering Strait, the ice closed in, and the Vega was trapped for a long, dark winter. But thanks to Nordenskiöld’s administrative talent, the crew suffered none of the privations of prior expeditions – the man had even stocked festive decoration for the onboard Christmas party! After almost a year in polar captivity, the ice released the Vega from its clutch, and Nordenskiöld returned to Stockholm a hero – the first ever Arctic passage and the first circumnavigation of Eurasia.

Operation Wonderland: Frostnip for Germany

Even though the navigability of the Northeast Passage had been proven many times since Nordenskiöld’s successful attempt, no one ever harbored illusions of its practicality. That is, until a war changed everything, eliminating one alternative after another. In 1942, the Soviet war machine was gasping on all fronts. When the German occupation of Crimea cut off the USSR from the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic turned into the deadliest shipping lane in history, the vital Anglo-Soviet corridor through Iran simply could not keep up with materiel requirements.

Pressed by circumstances, the Allies redirected some convoys through Iceland and Alaska, towards the Arctic ports of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. The Kriegsmarine, well-positioned on both sides through Nazi-occupied Norway and Imperial Japan, made the first decisive step in the summer of 1942.

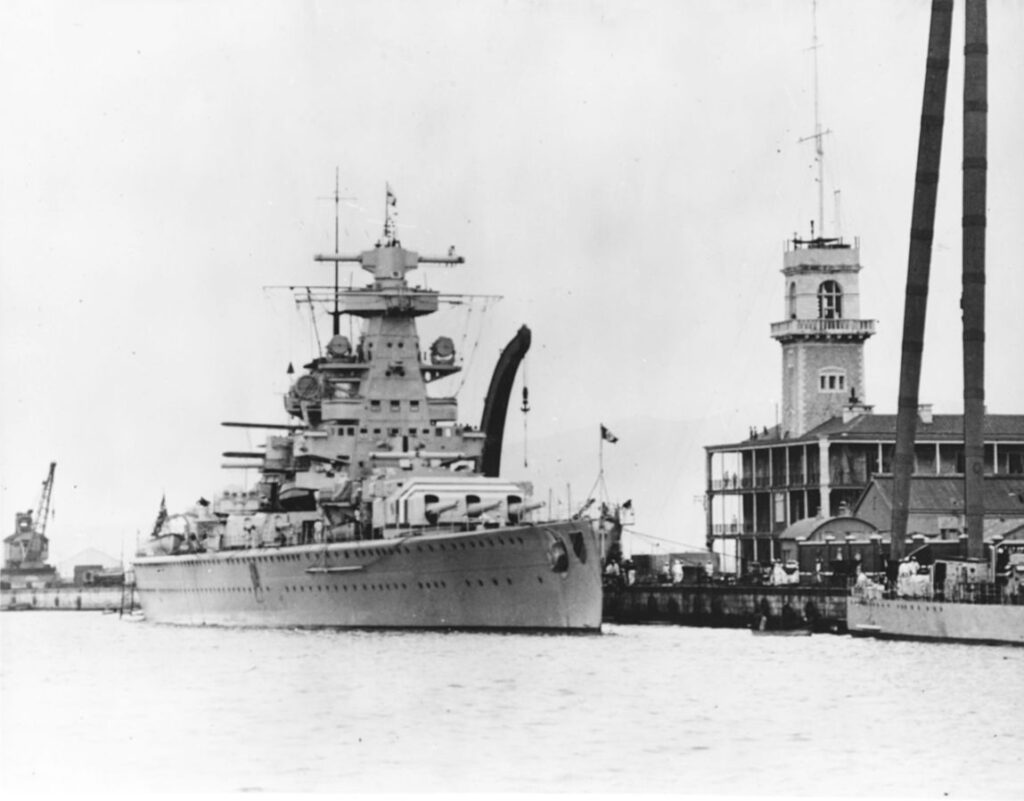

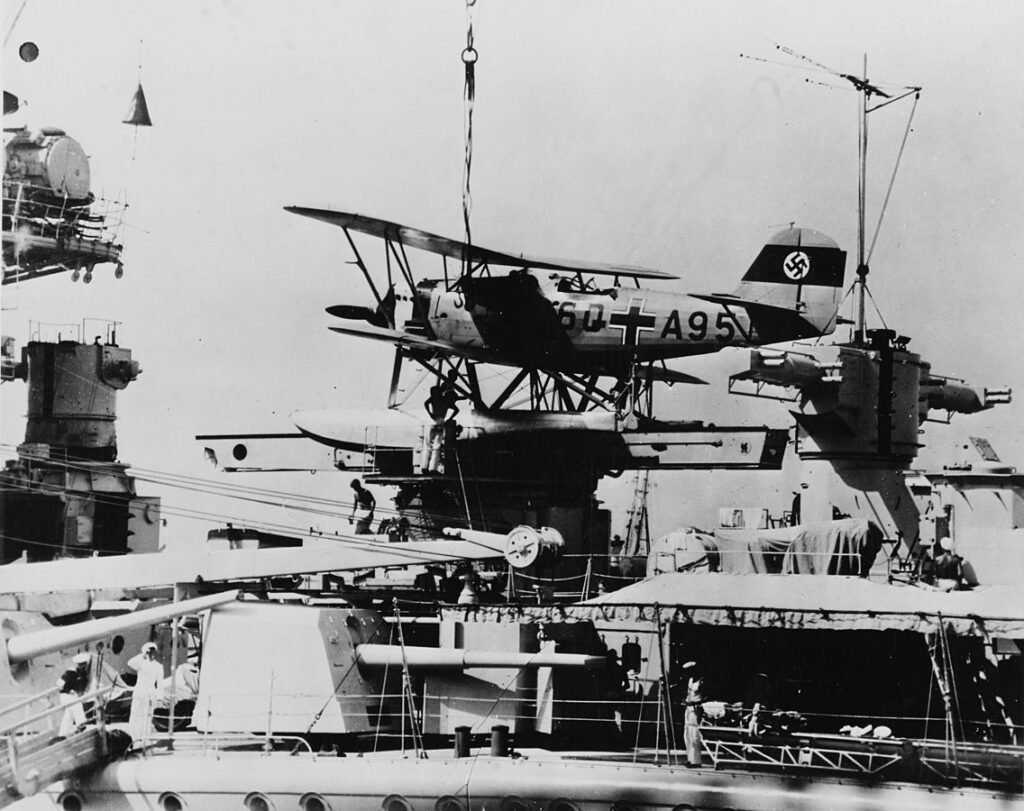

The main character in Operation Wunderland was the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer, a state-of-the-art vessel with enough fire power to lay waste to the entire Arctic. The Russians, however, were about to turn a former nemesis into a formidable ally – Mother Nature. The Kriegsmarine was not prepared for the intricacies of Arctic navigation and, despite Commander Wilhelm Meendsen-Bohlken’s brilliant seamanship, progress through the pack-ice was slow and excruciating. Foul weather turned away Admiral Scheer’s convoy of destroyers and U-boats, leaving the cruiser alone amidst a series of storms and permanent low visibility.

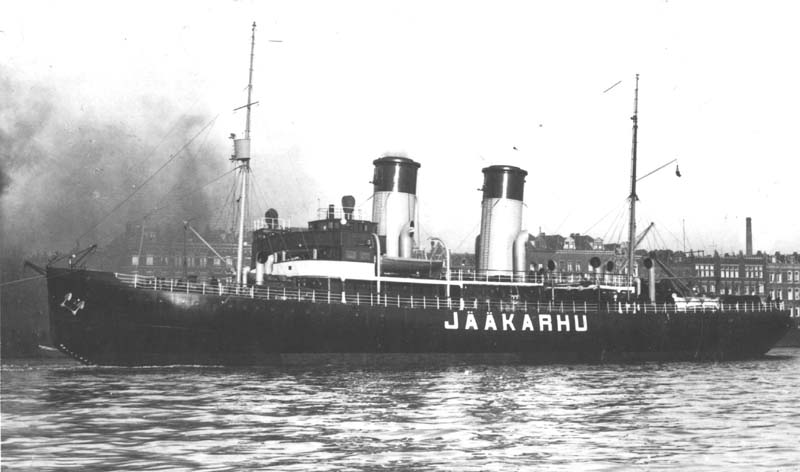

At first, the fog played in the Germans’ favor, hiding them from Soviet patrols in the Kara Sea, but as the cruiser approached Nansen Island, a mast appeared in the distance. It belonged to the legendary steamer Sibiryakov, the first vessel to complete the Arctic crossing without wintering. A clash was unavoidable. It took just four hits from the Admiral Scheer’s powerful guns to neutralize Sibiryakov, but the Russian crew fought till the end, with only 19 of the 104 men on board captured by the Germans. Before the surrender, one of the Soviet engineers opened the seacocks, scuttling the ship and drowning in the process. Despite the efforts of German operators to jam radio broadcasts from the Sibiryakov, a distress signal squeezed through, reaching nearby vessels. For Commander Meendsen-Bohlken, time was running out.

While the frantic news of the Kriegsmarine’s presence circulated the Arctic, more and more ice packed in the narrow Vilkitsky Strait, cutting off the Germans from the Allied convoys in the Laptev Sea. With Operation Wunderland’s main objective now beyond reach, the cruiser made a hurried attempt on the port of Dikson, which Meendsen-Bolken assumed almost undefended. He had no idea the port town had been reinforced with heavy guns on land and several icebreakers, including the auxiliary ship SKR-19 Semyon Dezhnyov. Surprized by the ferocious resistance, the Admiral Scheer failed to capture Dikson, losing precious time to the advancing ice floes. Crippled by the forces of nature and the sparse Soviet defenses, she returned to Norway.

The Ice Retreats: A Commercial Future for the Arctic?

As climate change decreased the density and reach of pack ice, profitable sailing in the Arctic no longer seemed like a fantasy. In 2017, the Russian tanker Christophe de Margerie made the first journey from Norway to South Korea, without being escorted by an icebreaker. This boosted Russia’s hopes for a direct maritime link between the giant Yamal gas field and the insatiable East Asian energy markets. And speaking of energy, global warming could not only grant full access for navigation in the Arctic but also allow exploration of what experts estimate to be 22% of the world’s undiscovered hydrocarbons.

Russia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, and the United States have already submitted claims for the right to explore the continental shelf of the Arctic Ocean, but as the northern boundaries of these countries come very close to one another, the political arena is ready for the first clashes. To make things even more complicated, China has initiated a “soft” offensive to establish a presence in the region, as part of its effort to circumvent the maritime chokepoints at Malacca, Bab-el-Mandeb, and Suez.

Russia is still the undisputed naval hegemon of the North, with a mature fleet of 51 icebreakers and a strategy as grand as it is risky. In 2022, global media erupted with the news of the ongoing construction of a new $110-billion mega port on the Taimyr Peninsula, planned by the Kremlin as the leading oil hub of the North. This and several other smaller projects are part of the country’s Northern Sea Route (Sevmorput) plan to redirect marine traffic from Suez and Panama. But while Russia is making the most assertive steps, it also faces the challenge of financing the staggering infrastructure needed for commercial navigation and hydrocarbon extraction. With Moscow’s finances stretched almost to breaking point, the completion of these projects will depend on funding and long-term political support from abroad.

As each contender in the Arctic race has temporary advantages and long-term weaknesses, the conflict now only exists on paper, but, in an increasingly unstable world with depleting resources, the Northeast Passage might heat up in more ways than one.

Want to read more about the Arctic? Click here to read about nuclear-powered icebreaker Yamal!

The Shipyard