A peculiar species of cargo ship populated the Great Lakes in the late 1800s – the whaleback. Designed by Scottish captain and inventor Alexander McDougall, these barge-inspired steamers sported extravagant cigar-shaped hulls with a continuous curve, not unlike the body of a whale. McDougall had often observed how shallow waters and narrow canals limited the size of most lake barges. Prior attempts to overcome this inefficiency included towing several barges with a single powered vessel, but as soon as wind and waves came into play, these consorts had a hard time keeping a straight line. McDougall’s deceptively simple solution was a hull-design allowing waves to wash over the deck, instead of smashing against the sides. The result – eighty years of innovation, triumph, and tragedy.

SS Colgate Hoyt: The First Self-Powered

Built in 1890 in Duluth, Minnesota, the first of McDougall’s whales to sail under her own power was an 84 m single-screw with two boilers. Nine years later, while towing barge 115 with a load of iron ore through a storm, the lines broke and the barge drifted away. The Colgate Hoyt attempted a search, but fuel was running low, and the captain soon gave up. The 115 drifted for five days before it emerged near Marathon, Ontario, and beached on Pic Island. All crew members made it back to safety on a tiny raft. The Colgate Hoyt was renamed Bay City in 1905, then Thurmond in 1909.

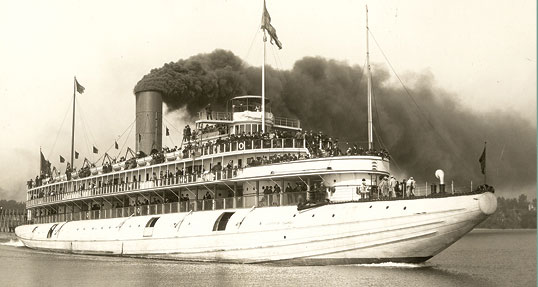

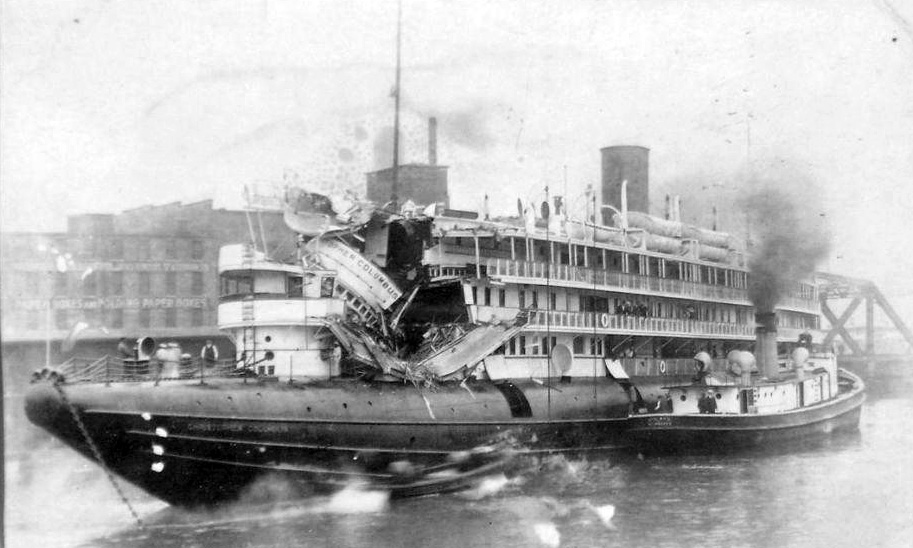

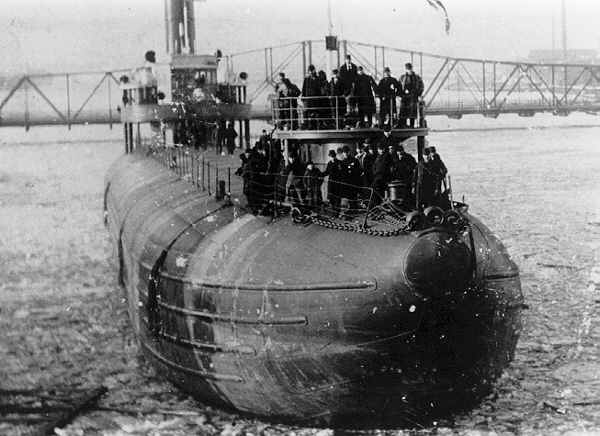

SS Christopher Columbus: The Only Passenger Whaleback

Three years after the Colgate Hoyt, the SS Christopher Columbus left the docks of the American Steel Barge Company in Superior, Wisconsin. The longest whaleback built to date (110 m), she was the only one to ever carry passengers – first from Chicago Downtown to the Columbian Exposition, then on leisure trips around the Great Lakes.

The propulsion system consisted of two Samuel F. Hodge & Co. reciprocating triple-expansion steam engines, fed by six boilers to produce the liner’s 3,000 horsepower and top speed of 17 knots. Nine watertight compartments and ten steam pumps kept guard against hull flooding – a daily risk on the notoriously moody lakes. Two decks (later three) spread across six turrets above the rounded hull. Oak walls lined the interiors, complemented by marble, etched glass, luxurious furniture, and fine carpets – all bathed in electric light.

As for accidents, the Christopher Columbus got a nasty bump on the head in 1917, when the Milwaukee River swept her away from the tugs, lashing her against the legs of a water tower. The reservoir crashed onto the stern, flattening the pilothouse and the front parts of three decks. 16 died and 20 were injured.

Her forty years of service were time enough for many legends, including one that the Christopher Columbus carried more passengers across the lakes in her lifetime than any other ship. The ‘Queen of the Lakes’ retired in 1933 and was scrapped three years later at Manitowoc, Wisconsin.

SS Thomas Wilson: The First Casualty

An unassuming freighter for most of its existence, the Thomas Wilson gained considerable fame as a shipwreck. On 7 June 1902, soon after departing fully loaded from Duluth harbor on Lake Superior, and with cargo hatches still open, she encountered inbound wooden steamer George Hadley. The two captains maneuvered to avoid collision, but after a fatal miscommunication, the Hadley rammed the Wilson, then pulled out, causing the latter to roll over to port, before up-righting herself again. She sank, bow first, within three minutes. Nine of the twenty men on board died.

The disaster brought about a new set of regulations at Duluth harbor: all ships leaving port must have their hatches closed; no ship may recoil immediately after collision; all ships must have signaling equipment on board; pilots must request additional confirmation of captain’s orders in proximity to other vessels.

Today, the wreck of the Thomas Wilson lies 21 meters beneath the surface of Lake Superior and is a popular attraction for divers.

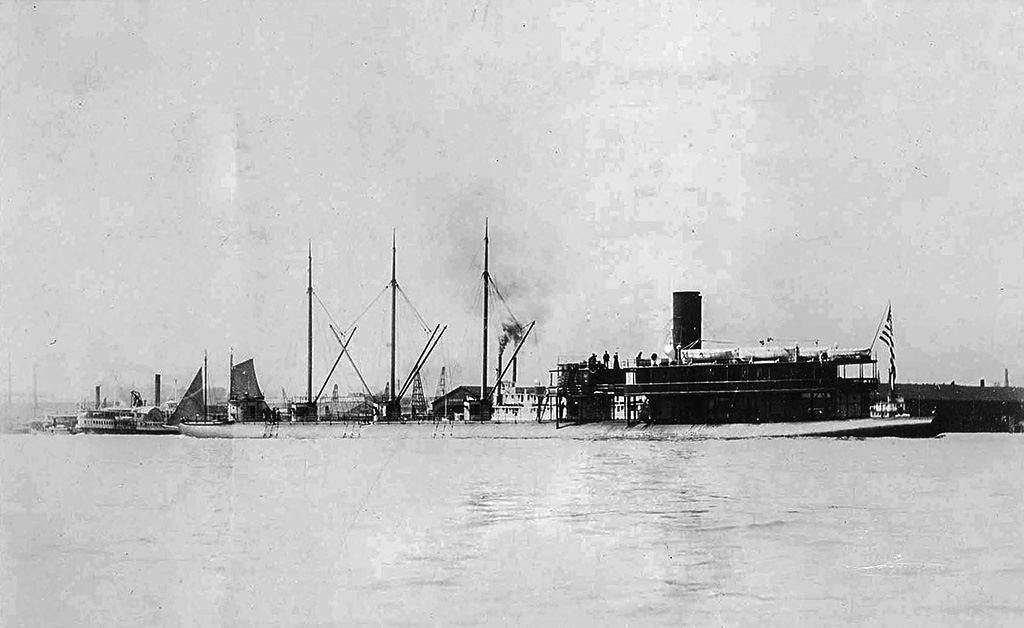

SS City of Everett: The First American Steamer to Circumnavigate the Globe

The first and last vessel out of McDougall’s new shipyard in Washington, the City of Everett, is not only the first American steamship to cross the Suez Canal, but also the first to complete a journey around the world.

This illustrious career was no coincidence – the ocean-going whaleback was financed by no other than John D. Rockefeller, and this meant scale. She was big – 111 meters – and it took ten rail cars to deliver her enormous engines from Detroit to the Pacific coast. The day of her launching was made a holiday in town, as the mayor of Everett requested all shops and offices to close at 3pm, so that people could attend the festivities. Ten thousand turned out to watch the christening of what was considered the largest ship in the Pacific at the time.

In 1897, the City of Everett left San Francisco, crossing the ocean to Manila and then Singapore, before docking at Calcutta. After a brief spell in India, she set out for Valencia via the Suez Canal, then Bilbao and across the Atlantic to South Carolina, completing the historic circumnavigation.

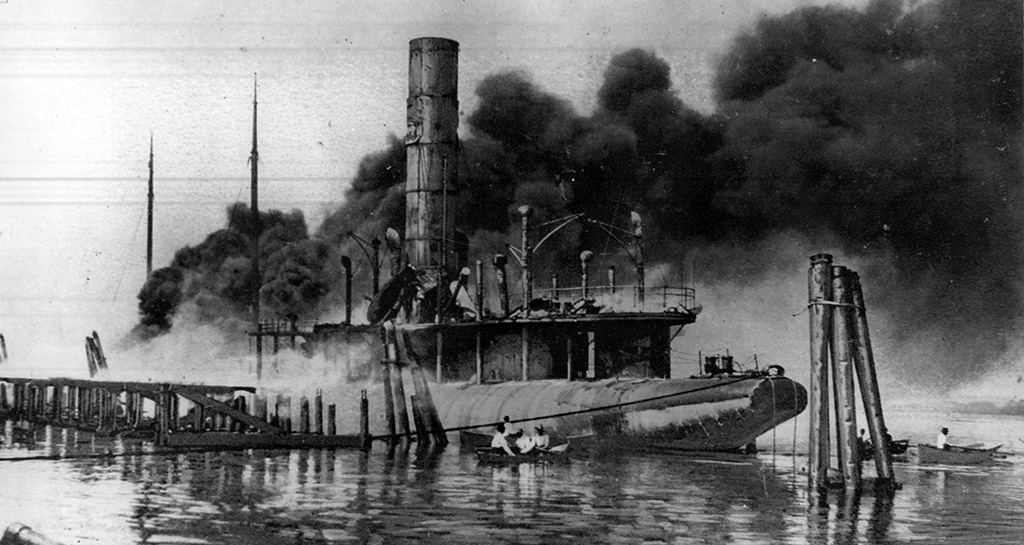

The rest of her career turned out less glorious, perhaps thanks to the deadliest natural disaster in history. On September 8, 1900, the Great Galveston Hurricane ravaged the Gulf coast with ferocity never seen before, causing thousands of deaths, including hundreds of fatalities as far north as Canada. The City of Everett was at the worst possible place, anchored right at Galveston Island. Without any hope for salvation, the storm sent her to the bottom.

A year later, the famous whaleback was salvaged and sold to Standard Oil for its tanker fleet, but the Everett’s losing streak was just beginning. First, an explosion injured several crew members in 1903. The fire raged for three days, fueled by the 12 million gallons of oil in the holds – a substantial loss even for today’s standards. Two years later, she collided with the Leif Erikson, tearing up the hull of the Norwegian steamer, badly enough to sink her within ten minutes. Despite a swift rescue operation, two Norwegians were never found. The Everett only suffered minor damage.

The tragic end came years later, after a New York sugar company became the Everett’s last owner. In October 1923, she took on a load of molasses at Santiago de Cuba and promptly made for New Orleans, but a storm hit the Gulf, and she foundered. “Am lowering boats; will sink soon,” was the first emergency broadcast of the captain. “Going down stern first,” was the last.

The following year, a bottle washed up on the shore near Miami with a piece of paper inside. “S.S. Everett. This is the last of us. To dear friends who find this, good-bye for ever and ever.”

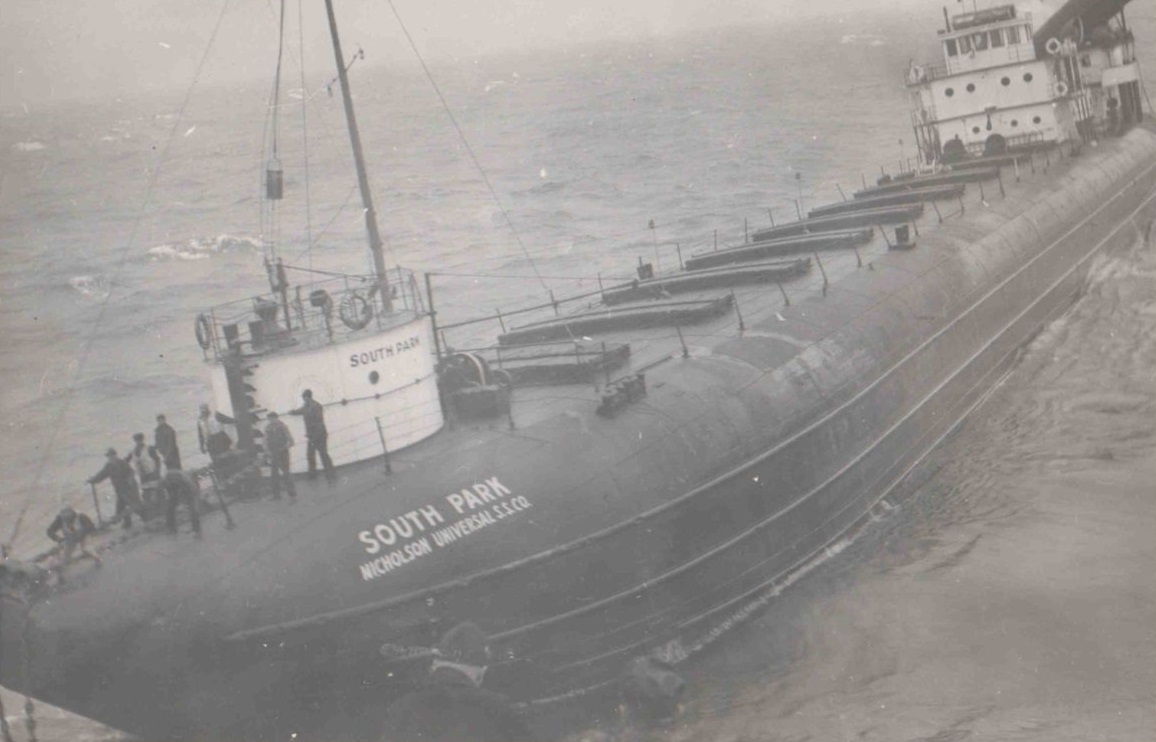

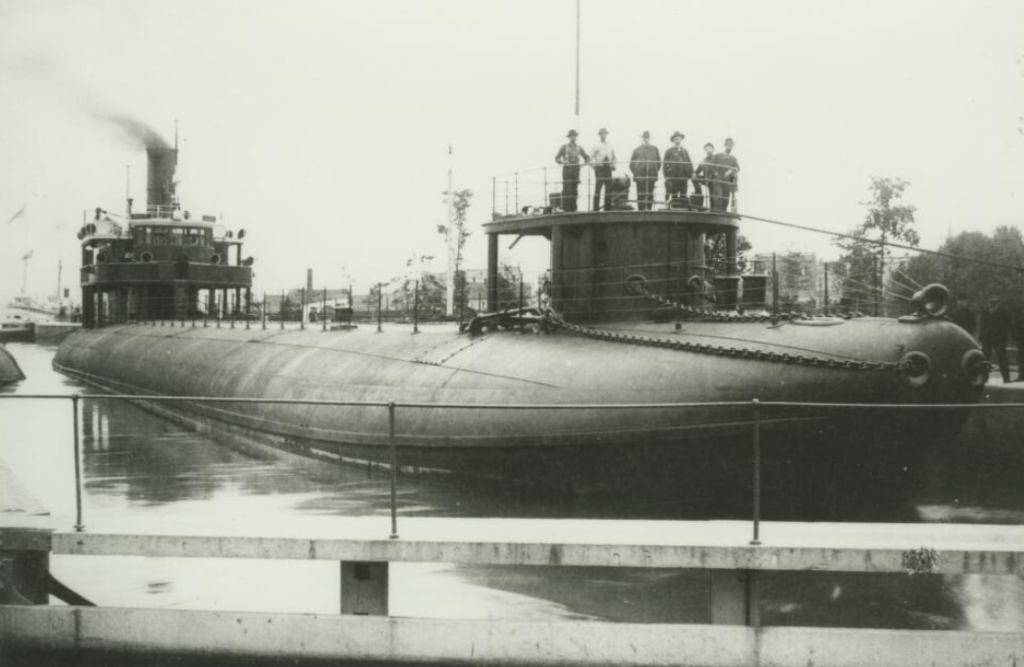

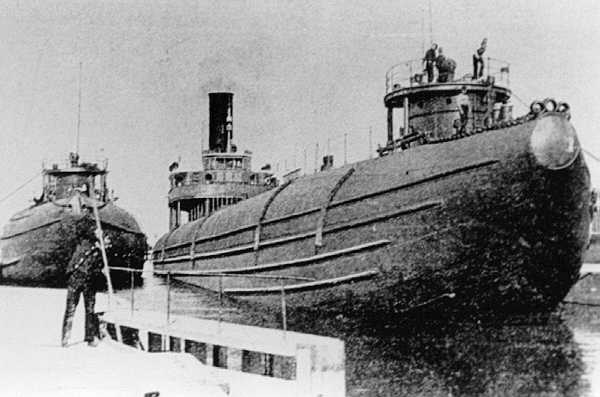

SS Meteor: Sole Survivor

Constructed in 1896 by the American Steel Barge Company at Superior, she had a length of 115.8 meters, beam of 13.7 meters, and gross registered tonnage of 2,750 tons. Launched under the name Frank Rockefeller, she was the 36th of 44 whaleback ships built between 1888 and 1898.

As the whaleback design allowed maximum cargo with minimum draft, she earned her keep carrying iron ore and coal between the ports of Lake Superior and the steelworks of Lake Erie. In 1900, she was sold to the Bessemer Steamship Company and, a year later, joined the Pittsburgh Steamship Company.

A long list of odd jobs marks her late years: sand dredger, excavator, car carrier, and eventually – a tanker named Meteor. She sailed under this name until 1969, when she ran aground off the coast of Marquette, Michigan, causing damage to the single hull. As the last of her breed, a decision was made to repair and preserve her as a museum ship. The Meteor is the only surviving whaleback and can be visited in her hometown Superior. The twelve cargo holds house an exhibition, showing the ship’s modest history.

The Extinction of a Species

Although it solved many problems, the whaleback design came with a few shortcomings of its own, which ultimately prevented it from conquering the mainstream.

Due to the rounded shape of the hull, hatches were smaller than on regular vessels and, thus, slower to load and unload. Many, like the City of Everett, had bolted hatches, which took so long to open and reseal, that the vessel became known among seamen as a floating workshop. In an industry where time is money, whalebacks quickly gained notoriety for their inefficiency at port. In addition, the hatches were designed to look as though they were part of the hull when closed, and this often led to damaged cover edges, compromising the watertightness of the seals. A more decisive factor, though, was the development of competing designs, which proved easier and more economic to build and operate.

But despite these flaws, Alexander McDougall’s singular fleet of steel steamers remains a respectable engineering feat, as well as a noteworthy episode in maritime history.

The Shipyard