We all know those photographs from the golden age of the ocean liner – giant black hulls with sharp, white superstructures towering above. Ever wondered why the hulls are black? The answer is surprisingly simple.

Ships with the prefix SS (meaning “steamship”, or originally, “screw steamer”), burned tons of coal to fire their boilers and generate steam. The black, greasy, and sooty fuel had to be loaded onto the ship trough doors and hatches in the shell-plating near the waterline. Only then could it travel down the chutes and land in the coal bunkers. It is easy to imagine how the clouds of coal-dust during loading would ruin the appearance of even the most beautiful hull, so, to keep the vessels looking neat and to save time cleaning the hulls in port every time, companies usually opted for dark colors.

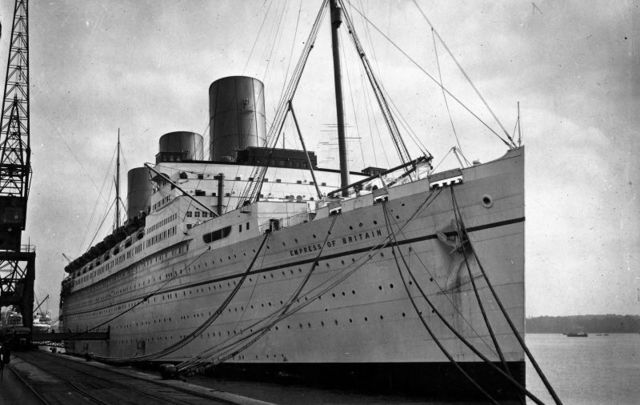

Some rare cases exist where ocean-liner hulls were painted white or grey, like the “Empress” liners of the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company. Completed in 1891, the RMS Empress of China, RMS Empress of India, and RMS Empress of Japan, all had white hulls despite burning coal. The shipping line stayed with white for its future vessels, most famous of which is perhaps the RMS Empress of Britain, built between 1928 and 1931. A well-known example of a grey hull is the SS Rotterdam, built in 1959 for the Holland America Line, and currently docked in the city of Rotterdam to serve as a hotel and museum. Despite these notable exceptions, light colors only became the norm after ships converted to oil. One good example of the transition was Cunard’s RMS Mauretania, which was modernized to burn oil instead of coal after World War I, and her black hull was re-painted white.

But the black hull remained an iconic symbol of the traditional ocean liner, long after steamships changed to motor ships and coal was no longer a factor in the industry. The tradition was passed on to some of the most iconic ocean liners, such as the SS Normandie, RMS Queen Mary, SS France, RMS Queen Elizabeth 2, and even the most recent one, Cunard’s RMS Queen Mary 2.

This brings us to the second question – why did the dark hull go extinct with the demise of the traditional ocean liner and the rise of the cruise ship? And again, there is very little science behind it. As many cruise ships were originally intended to sail in warm areas, white paint reflected the sun and kept the ship cooler (after all, we are talking about the dark age before air-conditioning). Then there was also the psychological effect of white being perceived as a feel-good color, giving the ship a neat and sharp look – a beautiful contrast against a blue-green tropical sea, perfect for advertising posters. White became the color of exotic vacations and clearly distinguished the ships used for fun from those used for transportation.

Over the years, cruise lines have experimented with green, blue, and even red hulls, but these are very rare. Some contemporary lines, such as Disney and Holland America Line, have decided in favor of the traditional dark hull. Disney chose a mix of blue and black, keeping a classical but still less-serious look. Other cruise lines, such as Norwegian, Dream Cruises, and AIDA, have experimented with colorful art, in order to distinguish their ships in an increasingly crowded market. The most recent addition to the cruise industry, Virgin Voyages’ Scarlet Lady, is entirely grey, except for the red stern and the picture of a mermaid on both sides of the hull. But there generally seems to be a trend for family-oriented cruise ships, which are all about entertainment and attractions, to prefer white hulls, whereas those focused on adult audiences with a taste for ocean-travel heritage, to retain the classic elegance of the dark hull.

In ocean liners and cruise ships alike, practical needs used to define design choices, but with the rise of motor ships and the emergence of on-board climate-control technologies, the color of a vessel’s hull is now the result of marketing decisions and visual differentiation.

The Shipyard