If you live in Europe, the Middle East, or Africa, most of the things you own have once been on a ship, passing through the Strait of Malacca. Some 500 miles (800 km) long and only 40 miles (65 km) wide at the narrow end, this maritime passage between the Indonesian island of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula is among the most important and contentious chokepoints in today’s global economy. As a major gateway in the Indian Ocean trade zone, the strait has long been China’s geostrategic nightmare, a colonial beehive, and a paradise for pirates.

Really, Why Is the Malacca Strait So Important?

By the will of nature, the Chinese mainland is guarded by the world’s highest mountains, some frightful deserts, and the thick rainforests of Southeast Asia. On the other end, the country’s vast coastline is fenced by a dense string of archipelagos that stretches from Bengal to Japan. The most direct navigable route between Europe and China passes through the Malacca Strait, thousands of miles shorter than the alternative passage through Lombok, Makassar, and Mindoro.

This natural fortress may have ensured China’s survival over the millennia, but the PRC’s recent global expansion has also highlighted a significant challenge. Almost inaccessible by land, countries in East Asia rely chiefly on maritime shipping to reach wealthy European markets and to obtain energy resources from the Middle East. With almost 90,000 ships each year, Malacca is now the busiest strait on the planet, with more than a quarter of the world’s traded goods passing through, most either coming from or going to China. Whoever has the upper hand in this narrow passage controls not only the Eurasian trade but also the economic and political fate of the world’s second-largest economy.

Origins: It Began with the Winds, Not the Europeans

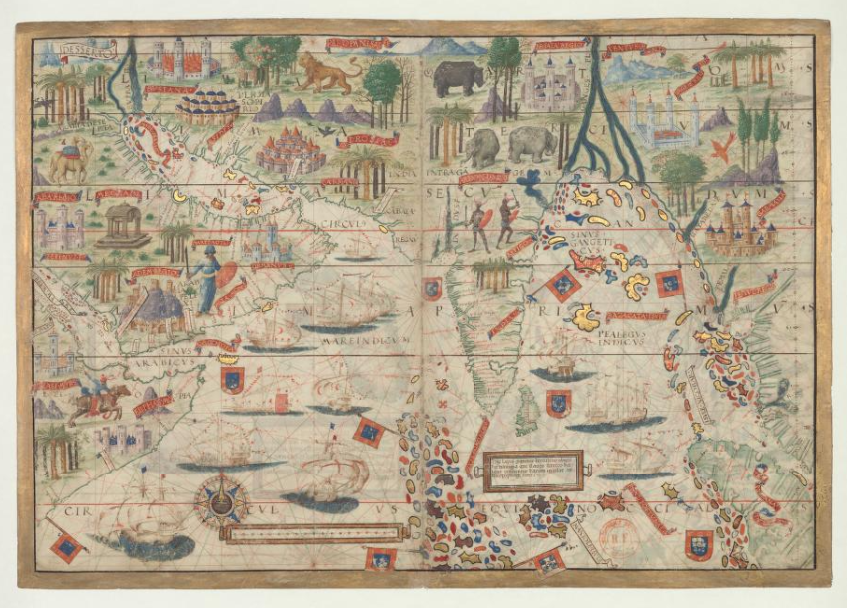

A thousand years before Europe’s first advances into maritime Asia, the Indian Ocean was already bustling with seaborne traders from East Africa, Persia, Arabia, India, China, and Japan. Powered by predictable monsoon patterns, called trade winds, merchant ships sailed away from the Asian mainland in the winter, across the Arabian Sea, and down the Swahili Coast of East Africa. The wind direction reversed in summer, allowing fleets to return to India and the Far East.

As a result of this seasonality, stopovers were longer than usual, with merchants waiting months for the winds to change direction. Travelers set up offices and second homes at ports along the way, forming multi-cultural melting pots, centuries before the first white face showed up at the local bazaars. Swahili served as lingua franca long before Portuguese or English, while Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam were the first religions to conquer the vast and diverse coastline. Vibrant merchant settlements formed in Mombasa, Aden, and Goa.

Srivijaya’s Marine Highway

In the 7th century, a wave of seafaring warriors (including a few pirates) conquered Sumatra and the adjacent regions, establishing their coalition as Southeast Asia’s undisputed naval hegemon. A typical thalassocracy, the Buddhist Srivijaya focused its resources on building an advanced navy and a network of well-managed entrepots for the growing China trade. At the ports of Kedah and Jambi, Chinese goods were reloaded on ships bound for Sri Lanka and Persia, while Arabian dhows at Basra transported the valuable cargoes along the East African coast. The Strait of Malacca was among the world’s most cosmopolitan regions, with Chinese, Javanese, Indian, and Arab merchants often treading the same streets.

As always, prosperity attracted envy. In the 11th century, the Indian kingdom of Chola attacked Srivijaya, occupying Java and capturing the Sumatran capital Palembang. Two centuries later, the weakened empire disintegrated, and the priceless chokepoint fell to the Javanese Hindu kingdom of Majapahit. Marked by turbulence, the Majapahit’s reign was even shorter, and, by the early 1400s, the Muslim Malacca Sultanate took over the strait. Protected by local seafaring peoples, the sultanate’s capital Malacca soon grew from a fishing village to Southeast Asia’s leading entrepot. Enforcing transparent customs duties, fair judicial procedures, and low corruption, the new port promised smooth sailing all the way. However, as the 16th century approached, new trouble was brewing on the other end of the world.

The Guns Arrive

Toward the end of the first millennium, one country rose to dominate European trade with the East. The Venetian colonial empire stretched across the Levant, reaching the western end of the Silk Roads to establish a firm grip on the overland routes into Asia. With its great fortunes and far-reaching political influence, Venice was getting ready to become the new Rome. This never happened. On 16 December 1497, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama located a maritime passage south of the Cape of Good Hope and sailed triumphantly into the Indian Ocean. Five months later, he disembarked his flagship São Gabriel in Kerala, bringing the Venetian trade monopoly to an end.

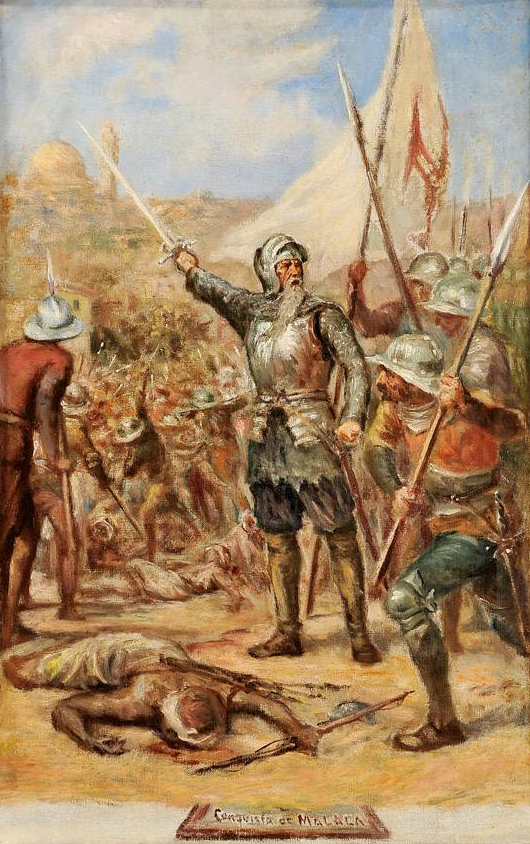

The Portuguese were quick learners, soon discovering the crucial role of the Malacca chokepoint for the China trade. Only 13 years after Vasco da Gama’s exploratory voyage to India, Alfonso da Albuquerque arrived at the vibrant city of Malacca. But this European brought no goods to trade – he brought cannons. On 24 August 1511, Portuguese forces stormed Malacca, and even though Albuquerque allowed the Hindus, Chinese, and Burmese of the city to evacuate, he ordered all Muslims to be massacred or sold into slavery. With the admiral’s talent for warfare exceeding his political acumen, the invaders failed to establish stability, opening the gates to chaos instead. As the regional balance collapsed, the Malacca Strait plunged into an era of war and piracy.

Warring States

Lured by the power vacuum on the China route, the sultan of Aceh in Northern Sumatra appealed to the Ottoman Empire for assistance against the Portuguese. Suleiman the Magnificent, a key Venetian ally on the Silk Road, was eager to respond. Already involved in a wider conflict against Portugal, Suleiman’s son Selim II dispatched a small fleet to Sumatra in 1566. The naval officers trained the Acehnese in contemporary warfare, while Ottoman gunsmiths laid the foundation of local firearms manufacturing. And although the Muslim alliance failed to curb Portuguese advances into Asia, another European power was about to change the game.

When the Amsterdam stock exchange opened doors in 1602, the very first corporation listed on it – the Dutch East India Company – set out on a mission to dethrone Portugal from the China trade. Despite Portugal’s firstcomer advantage, its traditional monarchy could not match the stock market’s power to raise money from the masses. With no shortage of investors, the Dutch quickly developed a formidable capacity for transporting goods and soldiers deep into the East. On a sticky summer morning in 1606, Portuguese Malacca woke up to the thunder of Dutch cannons.

Contrary to Amsterdam’s hopes, the tug-of-war with Portugal dragged on for decades, prompting the Netherlands to establish Batavia (today’s Jakarta) on the island of Java, redirecting their merchant fleets through the Sunda Strait instead. By the time Malacca finally fell to the Dutch in 1641, the East India Company had invested so much in the Javanese route it only kept Malacca to prevent other powers from seizing it. European conquest proved to be a double-edged sword for the strait’s future, giving rise to some truly cosmopolitan cities, while also fostering intense rivalry, which ultimately turned Malacca into a charming backwater.

Englishman in Penang

Toward the mid-18th century, after 150 years of bold and violent expansion in India and North America, the British rose to the top of the colonial game. But with the American Revolutionary War and the loss of its profitable Thirteen Colonies, London’s Asian ambitions soared. As the tea trade grew to unseen proportions, the British East India Company sought to establish a firmer grip on the route to China, including the Strait of Malacca.

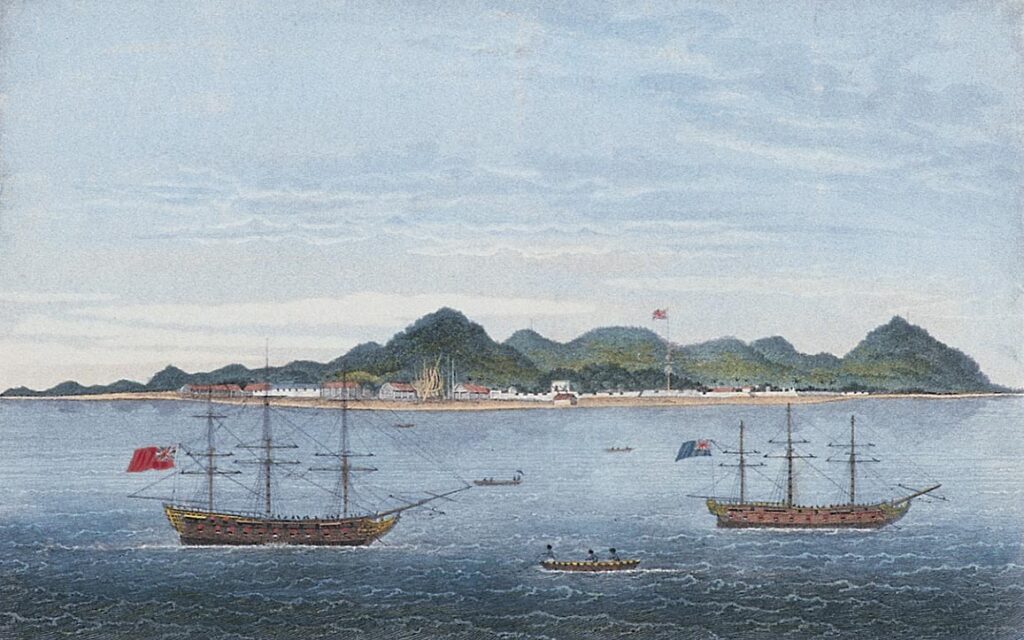

In the 1770s, explorer Captain Francis Light sailed to Kedah, proposing military support to the local sultan against internal and regional rivals. In exchange, the sultan offered the tiny island of Penang, which Light saw as a unique opportunity to secure British interests in the strait. For a few years, however, colonial bureaucrats in India brushed off the captain’s enthusiasm, until the news of American Independence reached Calcutta. In 1786, Light leased Penang on behalf of the British East India Company, renaming it Prince of Wales Island with Georgetown as capital.

Light had the far-sightedness to set up Georgetown as a free port from the start, attracting merchants from all over the region, who favored liberal Penang to the more-bureaucratic Batavia. Within a few decades, the port grew from a sleepy small town to a thriving entrepot, where Chinese, Indians, Malays, and Europeans lived together, traded, and intermarried.

The World After Napoleon

The Napoleonic Wars at the start of the 19th century threw the Old World in complete disarray, and with European colonialism reaching deep into the East, the consequences of Bonaparte’s rise and defeat reverberated throughout Asia. Following the 1810 French annexation of the Netherlands, British forces occupied Dutch colonies all over the world, including Java, until Napoleon’s defeat in 1815.

The 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty was a drastic reshuffling of the colonial world, with Britain withdrawing from Java and Sumatra in exchange for complete control over the Malay Peninsula. Following an agreement to swap British Bencoolen for Dutch Malacca, London decided to incorporate the latter with Penang and Singapore into a single colony, the Straits Settlements. Despite the initial choice of Penang for the capital, Singapore soon took the lead and kept it until the colony’s dissolution in 1946.

Waking a Dragon

Winters are harsh in Beijing. Far away from any tropical trade winds, the icy breath of Siberia wheezes through the narrow streets. And even though December 2001 was no exception, the Chinese capital buzzed with anticipation – after decades of negotiations, the People’s Republic was finally joining the World Trade Organization. China’s return to the world market was about to unleash one of the great economic miracles of our time, breathing new life into the ancient port towns along the Malacca Strait.

True, the chokepoint had never been asleep, especially with Japan’s post-war economic boom, but numbers do not lie. In the first 20 years of China’s WTO membership, its exports soared from $272 billion to $3.5 trillion, while traffic through the Malacca Strait in the same period grew from 59,000 to more than 80,000 vessels. But there was more to traffic than just the number of ships. Back in 2000, the Maersk Sovereign-class ruled the waves with maximum capacity of 8,000 TEU, while the current largest container ship (MSC Irina, herself built in China) can easily carry three times as much.

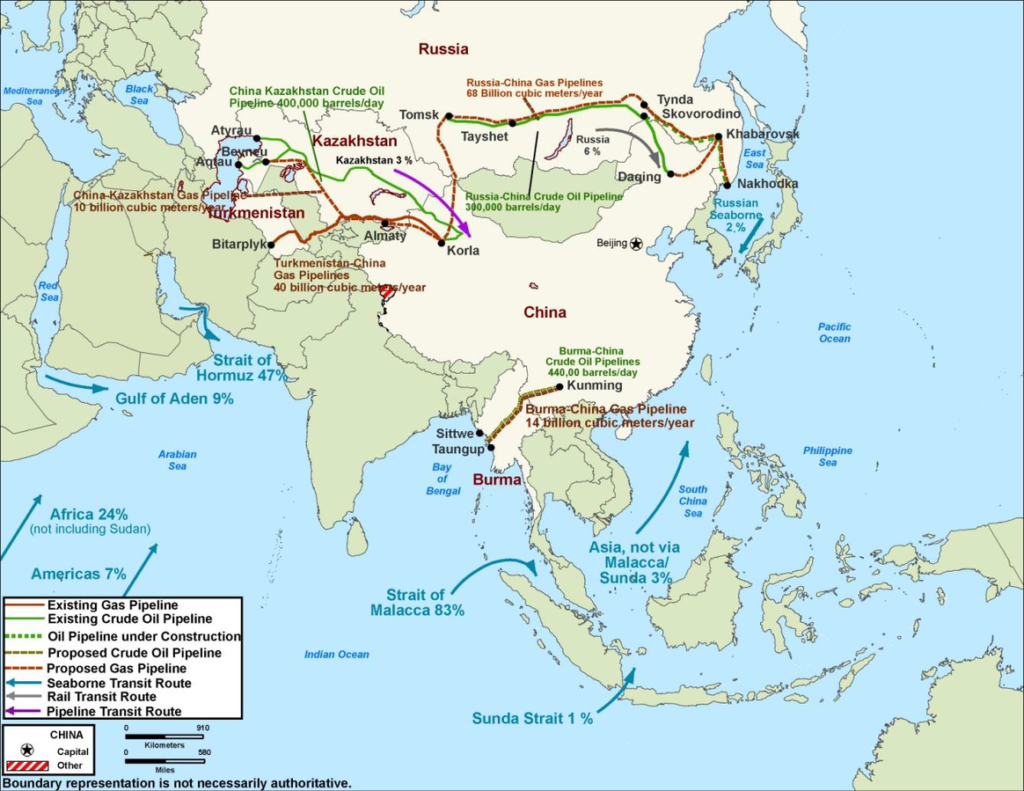

Tackling the Malacca Dilemma

With China joining the global superpower club, the Strait of Malacca once again simmers with contention. Supported by a wide network of allies, the United States Navy patrols the East Asian chokepoints, adding a significant risk factor to China’s already complicated geostrategic chessboard. And while the PRC has made efforts to diversify its access to critical resources, the process has been turbulent and only partially successful. For example, despite several major gas pipelines from Central Asia and Russia, more than 80% of China’s oil imports still pass through Malacca.

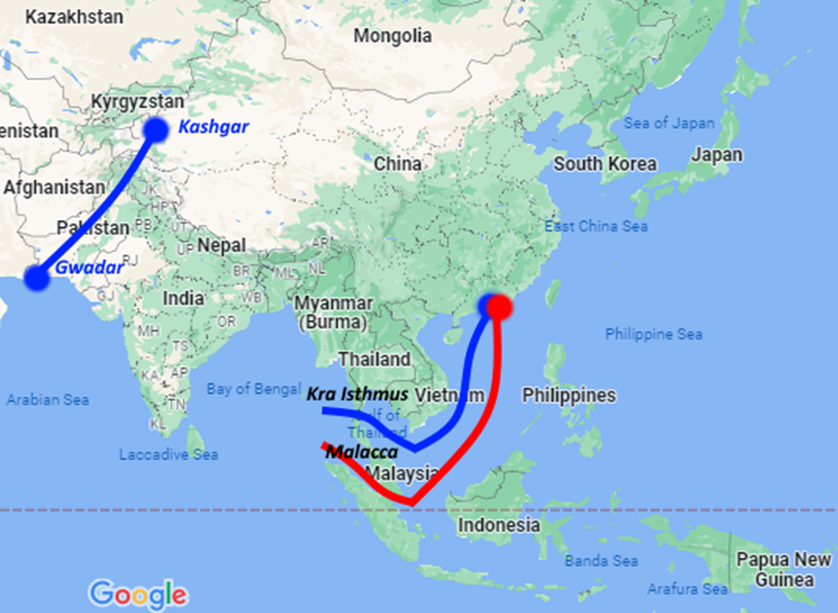

In 2014, Malaysia launched the Melaka Gateway, a Chinese-backed project to build a world-class port near the city of Malacca, but political maneuvering and technical difficulties brought the project to a halt in 2020. At the time of writing, the Melaka Gateway is regaining political support in Malaysia, but completion is still far off. In 2015, China and Pakistan signed the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, planning the expansion of Gwadar Port and the construction of a road network between the port and China’s westernmost city of Kashgar. Despite the challenging topography and political instability in the region, the corridor entered partial operation, promising some relief from the Malaccan monopoly.

Finally, China’s boldest move to escape the Malacca chokepoint was a proposal to finance a new canal, cutting through Thailand’s Kra Isthmus to form a direct connection between the South China Sea and the Andaman Sea. Seen by many as the East Asian Suez, opposition to the project has been fierce, with no firm decisions so far.

The Future of Malacca: Business as Usual

Despite numerous historic and contemporary attempts to escape the Malacca monopoly, the strait’s future looks as reassuring as its past. Changing the status quo (especially one backed by a trio of politics, business, and nature) is a difficult task. In a world where oil from the Middle East powers the Chinese industrial machine to satisfy global demand for manufactured goods, the importance of this tiny blue strip on the Asian map is likely to remain for a long time to come.

The Shipyard